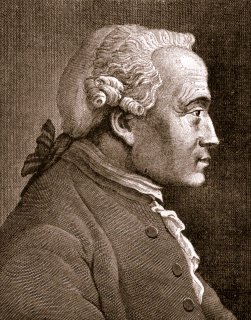

22 April: Boreham on Immanuel Kant

An Intellectual Adventurer

An Intellectual AdventurerToday marks the birthday of the most audacious abstract philosopher of all time. Immanuel Kant looked for all the world as if he had been made in a Giant and Dwarf Factory, a factory in which an impish apprentice had mischievously attached the head of a giant to the body of a dwarf, and, just because the result looked so freakish and fantastic, had allowed the grotesque combination to remain. Immanuel Kant was a dwarf; not a sinewy and powerful dwarf like Hugo's Quasimodo, but a slim little dwarf with hollow chest, slender girth and limbs like broomsticks. Yet, dwarf as he was, he must have stood very near the light; for some fragment of his monstrous shadow falls athwart every sheet of manuscript that Europe has produced since he appeared.

Kant was one of the few great metaphysicians who took plenty of time to think things out. He was nearly 63 when he presented the world with his "Kritik der reinen Vernunft," a work that has done more to shape the speculations of mankind than any other volume of the kind ever published. Few men wait until they are 60 before making their debut in the republic of letters. But then, nothing that Kant said or did was in line with traditional custom and procedure.

All Continents Crowd A Philosopher’s Cottage

During those 60 years, his life, judged from the outside, was the life of an automaton. "Getting up," says Heine, "drinking coffee, lecturing, eating, going for a walk; everything had its fixed time; and the neighbours knew that it must be exactly half-past-four when Immanuel Kant, in his grey frock-coat, and with his Spanish cane in his hand, stepped from his front door and set out for his constitutional." But those neighbours, who regarded the odd little man as a bundle of eccentricities, had no conception of the boundless immensities, the world-shattering ideas, that were revolving in his massive brain.

Cabin'd, Cribb'd and confin'd as his existence seemed to be, Immanuel Kant was nevertheless a citizen of the world. His modest chamber was a camera obscura on the white table of which all the globe was reflected in miniature. "In his life of Kant," Mr. Houston T. Chamberlain points out that, whilst Kant had an astounding power of abstraction, he had not in the strict sense, an abstract mind. He read everything that he could lay his hands on; books of travel, history, geography, science, fiction; his hungry mind welcomed them all. One has only to read at random a page of his in order to see that, from that small window of his, he had a view of the whole wide world. He graphically describes mountains, deserts, forests, oceans and waterfalls; yet he had seen none of them. He sat in his chair and summoned all five continents to his fireside. And all five continents came.

Kant Moved Stone That Set Avalanche In Motion

Leaving the publication of his work until his hair was grey and his face wrinkled with age, he was approaching the limit of three-score-years-and-ten before he tasted anything that smacked of fame. The world awoke with a start to the discovery that a new light had broken upon Europe. A quaint little thinker at Konigsberg had asked himself the meaning and purpose of human existence, and had answered his own questions more clearly and more cogently than such questions had ever been answered before. He had faced with perfect frankness the problems that had puzzled men for centuries, with fine catholicity he had welcomed knowledge from whatever source it chanced to have come; with magnificent scorn he had waved aside all dogmatism—whether theological, political or scientific—unless the dogmatist could produce reliable evidence in support of his conclusions. He was singularly happy in the period into which he was born. Schopenhauer has pointed out that, had he appeared a generation or two earlier, he would certainly have been denied the intellectual freedom that he actually enjoyed; and it is very certain that his speculations and deductions would have been ruthlessly censored today. For he was the apostle of freedom.

Massive minds, like that of Kant, often exert themselves most effectively, not directly but indirectly. A man like Kant does his best work, not in his own proper person, but by means of the disciples who rise up to succeed him and carry on his work. The eighteenth century was dominated by three remarkable men—Immanuel Kant, Samuel Johnson and John Wesley. We owe very much, of course, to the work done by each of them; but we owe still more to the influence which they exerted over their disciples and successors. After the death of Kant we had a great philosophical revival; after the death of Johnson we had a great literary revival; and after the death of Wesley we had a great religious revival. Immediately following the life of Kant, we have the work of Hegel and Schopenhauer, of Schleiermacher and Herbart, of Goethe and Schilling, of Thomas Brown and Jeremy Bentham, of Sir James Mackintosh and Sir William Hamilton, of Johann Fichte and of many others. Immanuel Kant stands, therefore, as a pioneer. Many of his doctrines still hold the field: and even those of his conclusions that have been modified or refuted led to discussions out of which a more just and adequate view of life emerged. He deserves well of mankind, and, happily, the generations have treasured the memory of the wise little man with growing reverence and gratitude.

F W Boreham

Image: Immanuel Kant

<< Home