19 April: Boreham on George Gordon Byron

Prince Charming

Prince CharmingOn the 19th of April we reflect, with an interest not unmixed with curiosity, that the most desolating death recorded in our literary annals occurred on that day. There was no city in Europe in which Byron was not wept. Never before; nor since, has the passing of a poet cast such a gloom over all nations. "I first heard the news," says Mrs. Carlyle, "in a room full of people. Had I been told that the sun and moon had fallen out of their spheres, it could not have conveyed to me the feeling of a more awful blank than did those melancholy words." "It is as if the very sun had been extinguished," exclaimed Sir Walter Scott. Indeed, all the records of the time seem to the cold judgement of a later generation, to be tinged with funereal extravagance.

Tennyson, however, was fifteen—just old enough to be infected by the enthusiasms and excitements of the period. "As a boy," he says, "I was an enormous admirer of Byron. I shall never forget hearing the news of his death. It seemed an awful calamity. I remember rushing out of doors, sitting down by myself, crying aloud, and writing on the sandstone: 'Byron is dead!' I thought the whole world was at an end. Everything was over and finished for everyone. Byron was dead and nothing else altered." Tennyson was old enough to feel and to share the poignant emotions of the hour; but he was young enough to be able to review his youthful judgment in the colder light of maturer years. His mind suffered a recoil. In the heyday of his own greatness he felt a trifle ashamed of his juvenile adoration; he could in manhood, see little that was supremely admirable in his boyish hero. His idol had fallen.

The Magnetic Quality Of A Superb Egotism

No country—not even Italy or Greece—has produced so many popular poets as has England; but even England has produced no poet whose popularity, whilst it lasted, could compare with that of Byron. We ask ourselves why; and the answer is that the fascination of Byron lay in his colossal egotism. His world consisted of but one hemisphere, and that hemisphere was Byron. He was always magnificently himself. He never adopted opinions merely because those opinions were considered correct; he never said things merely because they were the things that a man was expected to say; he never attempted to conform to anybody else's standard of conduct. He knew his own mind, and, right or wrong, he went his own sweet way. The conventions of life were nothing to him; he cherished an ineffable scorn for all customs and precedents; a sublime recklessness was the most engaging of his qualities. He was distinctive, audacious, unpredictable, astonishing.

All this, displaying itself in a frame that was the perfect embodiment of manly grace, naturally attracted to him some of the most eminent personalities of his time. He was a superlatively magnetic figure, and he knew it. Knowing it, he took good care that his poems should be mere reflections of his own vivid and glamorous self. Without reticence and almost without self-respect, he stripped his soul stark naked, made the public the confidant of his innermost emotions, and poured all his bitterness into its sympathetic ear. It was Byron writing Byron all the time. As Macaulay puts it, he was himself the beginning, the middle, and the end of all his own poetry, the hero of every tale, the dominant object in every landscape. We have only to glance a second time at all the most splendid characters in his pages in order to recognise that, in each, we are confronting, in a new but unmistakable form, the dark and melancholy figure of Lord Byron himself. That figure stands, and will for centuries stand, as the embodiment of the most intriguing pessimism and the most daring egotism that the realm of English letters has ever produced.

The Subtle Force Of An Infectious Patriotism

It is the distinction of Byron that he was, at one and the same time, an intense patriot and an ardent cosmopolite. He loved England with all his heart and soul, and would have revelled in the luxury of laying down his life for her. Moreover, he did what very few patriots have ever succeeded in doing; he made England loved abroad. Mazzini, on behalf of Italy, and Castlelar, on behalf of Spain, and Hippolyte Taine, on behalf of France, all testify to the fact that it was Byron who won for England the admiration and affection of Europe. It was partly for this reason that the whole world felt its grief so poignantly when, still in his youth, he passed away. It may be said that, in the case of Byron, death was considerately more exacting than in the cases of most of our minstrels and masters. More of him died.

Byron was sick of life long before the end came. His health was shattered by his excesses. His hair turned white as snow. His food furnished neither enjoyment nor nourishment. His body was withered by a consuming fever. His reason, with all its brilliant powers and masterly attributes, was seriously threatened. Yet everybody who knew him, either personally or through his writings, loved him. At 24 he had the world at his feet; and, from that time to the end, he walked in a dazzling blaze of popularity. He was, as none of his predecessors had ever been, the poet of the entire British people. Everybody appreciated his genius, pitied his frailties, and, when reminded of his vices, charitably remembered that, his father being a profligate and his mother a fiend, not one solitary influence that might have uplifted and ennobled him had been brought to bear on his boyhood. Generations may come and go, but on the 19th of April every year, with unerring regularity, a glorious wreath of Marechal Niel roses is placed by an anonymous hand on the statue of Lord Byron in Hyde Park, London. Have our annals ever known, within the compass of a single personality, such an amazing combination of conflicting elements as met in him?

F W Boreham

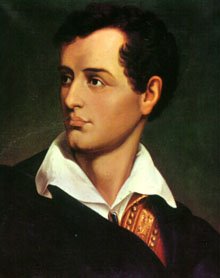

Image: Lord Byron

<< Home