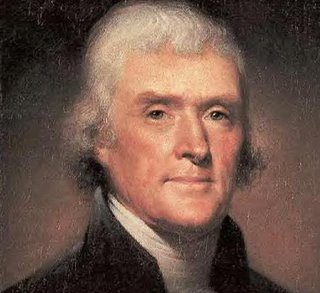

13 April: Boreham on Thomas Jefferson

The Author of the Charter

The Author of the CharterThe historic Declaration of Independ-ence was drawn up by Thomas Jefferson, whose birthday this is. Since Jefferson first saw the light in 1743, we celebrate this year his bicentenary.[1] Jefferson holds one really amazing record. Appointed to draft the most momentous instrument in modern history, he consulted no book, statute, document or authority of any kind. Out of his own head, as the phrase goes, he drew up the Magna Charta of the West, and, except that one or two paragraphs—such, for example, as the section that provided for the emancipation of the slaves—were deleted, the Declaration stands today almost word for word as it stood in Jefferson's roughly-pencilled script.

There was nothing of the Log-Cabin-to-White House type about Jefferson. The ball was at his feet from the start. Enjoying every advantage that could accrue from wealth, culture and overseas travel, he possessed in addition the genius to see how such good fortune could be turned to the best possible account. Moreover, Nature conspired with environment in making a man of him. Of striking and attractive appearance, he seemed born to command. Like Lincoln, he was excessively tall and loose-limbed; but, unlike his illustrious successor, he never allowed his clothes to disgrace him. Endowed with sparkle and vivacity, passionately fond of music and an excellent dancer, a skilful horseman and a versatile athlete, Jefferson never lacked agreeable companions and he adorned every circle he joined. He spoke French, Italian, and Spanish fluently and German moderately well. He never tired of mathematics and mechanics, and the natural sciences were child's play to him.

Knight Who Was Transformed Into A Rebel

Yet, despite the multiplicity of his gifts, graces and accomplishments, nothing so well became him as his perfect naturalness and exquisite simplicity. He had not a dram of envy in his entire composition. John Adams, who preceded him in the Presidency, was his most powerful rival, yet the finest tributes we possess to the personality and work of Adams have come to us from the lips and pen of Jefferson. Jefferson was magnificently poised. He could stand on his dignity, as his exalted position required, but affectation was loathsome to him. On the day of his inauguration as President he wore a neat suit of plainest cloth. Without a guard or attendant of any kind, he rode to the Capitol on horseback, instead of driving in the conventional coach-and-six, with footmen and outriders. And, on arrival, he dismounted without assistance and hitched his bridle to a fence! Like Addison, one of the greatest of British statesmen, he was no orator. Addison once attempted to address Parliament, broke down, and never repeated the experiment.

None of the early American Presidents acquired the arts of rhetoric. Washington and Adams seldom, if ever, spoke for ten minutes. "And," says Adams, "during the whole time I sat in Congress with Mr. Jefferson, I never heard him utter three sentences together." Yet, like Addison in the one hemisphere and Washington in the other, Jefferson was one of the shrewdest and wisest of counsellors, and his colleagues hung upon his lips as though their very lives depended on his words. In 1775 America's zero hour struck. In opening Parliament at Westminster, George the Third branded the Americans as rebels, recommended the employment of violent measures against them and authorised the confiscation of their vessels and the impressment in the British navy of their crews. Franklin, Washington, Adams, and Jefferson, loyal to the great English tradition, had hoped against hope for conciliation. They dreaded nothing more than a break with the Motherland. But this was too much. It goaded them to the point of madness and left no course open to them but the red road of revolution. By this time Jefferson was 32, happily married, prospering in his profession and with no desire in the world stronger than his desire for peace.

The Inspiration Of An Immortal Document

Realising that a crisis of the first magnitude had developed, Congress chose five men to handle the delicate and menacing situation. They were selected by ballot and Jefferson topped the poll. Particular tasks were then allotted. Washington was made commander-in-chief because of his flair for military movement; Franklin, because he had exhibited a rare skill in the arts of diplomacy, was sent to Paris to court the co-operation of the French people; while Jefferson, because of his ability as a lawyer and his sterling commonsense, was entrusted with the responsibility of drawing up the Declaration of Independence. Sir George Otto Trevelyan says that, in the history of modern civilisation, there are three documents, all extremely brief, that stand in a class by themselves—Queen Elizabeth's speech at Tilbury, Jefferson's Declaration of Independence and Abraham Lincoln's oration on the battlefield of Gettysburg. All three were singularly effortless and spontaneous.

Jefferson wrote out the Declaration with a free and swiftly-moving hand. He made few corrections or amendments, and, when he handed his manuscript to his colleagues, they felt that it was the crystal-clear articulation of the nation's angry heart. Twenty-four years after the adoption of his Declaration, Jefferson was made President, and four years later he was re-elected. When in 1826, the Jubilee of Independence was celebrated, Adams, the second President, and he, the third, were still living. Adams was 91, Jefferson 83. It was decided to make the Day of Jubilee July 4, 1826, a day in honour of the two grizzled veterans. Their names were emblazoned on every building and toasted at every feast. And, by one of the most striking coincidences in history, both Adams and Jefferson passed away before the great day's sun had set.

F W Boreham

Image: Thomas Jefferson

[1] This editorial appears in the Hobart Mercury on July 3, 1943.

<< Home