12 April: Boreham on James Mackenzie

The Chivalry of Medicine

The Chivalry of MedicineToday the world in general, and the medical faculty in particular, will honour the birthday of one of the very greatest physicians of all time. Lord Moynihan, the president of the Royal College of Surgeons, declared that Sir James Mackenzie was the sanest and most powerful influence in English medicine for a whole generation: his presence a wealthy benefaction, his memory an abiding inspiration. Mackenzie was born on April 12, 1853. Reared in a Scottish home of the good old-fashioned type, he plodded through his medical course, and, on obtaining his diploma, set up as a general practitioner in Burnley. In the heart of a great industrial area in Lancashire, his time became engrossed with the ordinary everyday diseases of ordinary everyday people. But Mackenzie had reasons of his own for concentrating on the heart. He and his brother, a clergyman, were both the victims of angina; and the brother eventually collapsed and died in his pulpit.

No patient was as welcome at Mackenzie's rooms at Burnley as a patient who brought some fresh phase of heart trouble for his investigation. The factory operatives who were worried by any form of palpitation or quickness of breath noticed that the Scottish physician seemed prepared to spend hours, if needs be, in thoroughly diagnosing their cases. In the great factory towns, gossip quickly spreads. A rumour runs through a mill almost as swiftly as it can be flashed along an electric cable. Everybody in Burnley soon knew that Dr. Mackenzie was ready to take infinite pains with any heart whose behaviour betrayed the slightest eccentricity; and, as a natural and inevitable consequence, men and women of every rank and class whose hearts came under suspicion of the most venial misdemeanour made a beaten track to his door.

Dispersing Clouds And Recalling Sunshine

There is a chapter in the history of Mackenzie's experiences in Burnley that reminds one of nothing so much as of a man who spends his life in visiting the shops in which caged birds are sold, buying up all the feathered captives, opening the wire doors and setting the imprisoned creatures free. For, after having made and recorded hundreds of observations, Mackenzie reached the deliberate conclusion that the cases that seemed at first blush to belong to the prevailing type were not as much alike as, on a superficial examination, they had seemed. There were hearts that, every now and again, missed a beat; hearts that sometimes raced and thumped in the most alarming fashion; and hearts that, for some strange reason, were addicted to other singular habits and idiosyncrasies. Until Mackenzie's time, it was taken for granted that hearts given to any of these whimsical and unseemly ways were a serious menace to the health, and even to the lives, of their possessors; and people so afflicted were subjected to the gravest warnings. The enterprising young doctor at Burnley, however, soon discovered that the human heart can acquire the oddest possible habits, and indulge in the strangest possible antics, without threatening it with any grave consequences. Mackenzie then classified with the utmost care the two classes of irregularity—the irregularities that matter and the irregularities that don't.

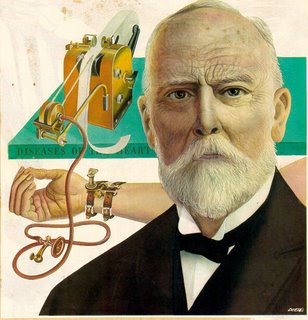

For some months he spent half his time in liberating such people from the shadowed destinies of which they had become the innocent and needless victims. Such an experience naturally established his fame; and, as an inevitable consequence, London called him. He was soon ensconced in comfortable quarters in Harley Street; a title was conferred; and Mackenzie came to be regarded as the most brilliant heart specialist of his day. His invention of the polygraph and other weird and ingenious mechanisims by which the action of the patient's heart could be automatically recorded were achievements sufficiently notable to secure for him a position of outstanding eminence.

The Splendour Of An Unselfish Descent

But Mackenzie's eventful life was destined to know yet one more dramatic change. After some years in London, consulted by people from all over the world whose hearts were causing them anxiety or alarm, a singular thought took possession of his mind, challenging him to a tremendous sacrifice. In London he had gained most valuable experience of heart diseases in their ultimate and most desperate forms. If only, armed with that knowledge, he could go back to an ordinary practice, study the cases in which such diseases were just beginning to betray their presence, and establish an institute in which all the phases of heart trouble could be made the subject of ceaseless research! Abandoning his commanding position in London, he daringly carried his altruistic scheme into actual operation; incalculably enriched the world by doing so; and then, at long last, died of the disease that had threatened him from boyhood.

His self-effacement was characteristic of him. In one sense at least, he who spent his life among sickly and stubborn hearts had himself a heart of gold. "He was a great man," exclaimed Lord Northcliffe, "a very great man!" "He was a good man," declared those who came into still closer touch with him, "a very good man!" To know him was to love him, and they loved him most who knew him best. The story of his married life is one of the most beautiful idylls of wedded love on record. "She is everything to me—just everything!" said he. "No woman was ever given such a generous love and companionship," said she. "Mackenzie was indeed the beloved physician," testified Lord Moynihan. "He made friends wherever he went; he stirred hope in hearts that were afraid, and strangely comforted every sufferer. Great men praised him for his knowledge and his wisdom; all people loved him for his tenderness, for his gentleness, for the power that gave them strength, for the courage that inspired them, and for the skill that saved them. He has bequeathed to his profession a name that will be cherished as long as the world endures."

F W Boreham

Image: James Mackenzie

<< Home