17 April: Boreham on Benjamin Franklin

The Father of a Nation

The Father of a NationToday the people of the United States, indeed of the whole world, pay homage to the illustrious memory of Benjamin Franklin, the man who, in the fine phrase of a French philosopher, tore the lightning from the skies and wrested the sceptre from the hands of tyrants. On April 17, 1790, full of years and honours, the majestic and patriarchal figure of Franklin passed from the imposing scene he had so long adorned. It would be difficult to exaggerate the value of the services he rendered to the American nation in the days of its infancy. If, as Sir J. R. Seely declares, the British Empire was created in a spasm of absentmindedness, then it may also be affirmed that the American nation was brought into existence in a gust of passion. Its foundations were laid by a handful of comparatively youthful hot-heads writhing with indignation at the tactlessness of British rulers.

Granted that their fury was a justifiable fury, and that many of those hot-heads contained most brilliant brains, it remains a matter of everlasting gratitude that, in that hour of destiny, the architects of western civilisation included among their number an elderly man of ripe experience and shrewd commonsense whose strong hand steadied and directed the exciting movements of that epoch-making crisis. When, as the climax of all their discussions and adventures, the historic Declaration of Independence was drafted, Benjamin Franklin sat among the creators of that celebrated instrument like a father with his boys gathered round him. He was 70. Washington, destined to become the first President, was 44; Adams, subsequently second President, 41; Jefferson, immediate draftsman of the Declaration and afterwards third President, 33; Hopkinson 39; Patrick Henry 40; and most of the others were young men about the same age. Franklin fathered them all and, in fathering them, fathered the nation, to the abiding profit of the American people and of all mankind.

How Nation's Torch-Bearer Began Career

In the school of hard knocks Franklin received the scanty education of which, as author, philosopher, plenipotentiary, statesman, and scientist, he made such excellent use. Like the old woman who lived in a shoe, his mother had so many children she didn't know what to do, and, as Benjamin came at the tail-end of the procession, his parents were getting a little tired of the business of rearing their offspring by the time he arrived. His father was a soap-boiler and tallow-chandler, and, following the line of least resistance, took Ben. into his own factory. The boy could never make up his mind which he hated most, the soap or the tallow, so, to settle the matter satisfactorily, he resolved to take the earliest opportunity of leaving them both. It chanced that, just at that moment an older brother, who had been more or less of a rolling stone, returned from his wanderings bringing with him a printing press. Announcing that he intended to set up in business as a printer and establish a newspaper, he invited Benjamin, then a boy of 11, to join his staff.

A contract was signed by which the younger brother undertook to serve the elder for 11 years. Among the stipulations were these: "Taverns, inns, or alehouses he shall not haunt. At cards, dice, and tables he shall not play. Matrimony he shall not contract." As soon as the newspaper was launched the elder brother, as editor, began to receive anonymous contributions of extraordinary merit. They became the outstanding feature of the journal. Everybody was talking about them. And not until long afterwards did James Franklin, the proprietor, guess that his mysterious contributor was no other than the young brother whom he had employed as his apprentice. After a few years the brothers quarrelled. Benjamin, then 17, ran away to Philadelphia. On the day of his arrival, while walking down Market St. devouring a cake that he had bought with the only coin that he possessed, he caught sight of a pretty girl standing in a doorway. He instantly vowed that he would marry her. And, some years afterwards, he did.

Conciliatory Influence In Age Of Conflict

Fame came to him in two very different ways. Always fond of experimenting, even as a small boy, he made a huge kite, fastened the string to a belt round his waist, and then, floating on a lake a mile wide, compelled his toy to tow him across. By a somewhat similar venture many years later, he discovered the electric energies inherent in lightning, and invented the lightning-conductor. Though this phase of his activity won for him the applause and the honours of the academic world, he will always be remembered as a skilful diplomat, a wise counsellor, and a powerful statesman. In those momentous days in which the relationship between the American and British peoples was strained to the breaking point, the eyes of the whole world were focused upon Franklin. He dared the English king, yet conducted the dangerous controversy with such adroitness and force that he won the admiration of the most eminent Englishmen, including the elder Pitt, Lord Chatham. True, Franklin failed to avert the dreadful conflict from which he shrank in horror, but, by his personal bearing and his persuasive eloquence, he won for himself and for his fellow-countrymen the profound respect alike of those who sympathised with the indignant colonists and of those who thought their policy misguided. Later on he represented his country with serene dignity and telling effect in delicate negotiations with the governments of France, Sweden, and Prussia. All Europe honoured him and, because of him, thought more highly of the nation whose ambassador he was. In his 85th year, pleading passionately for the emancipation of the slaves, he died, leaving a name that, as Bigelow avers, grows more lustrous and more loved with every year that passes.

F W Boreham

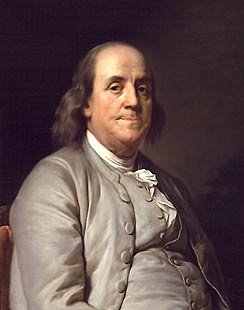

Image: Benjamin Franklin

<< Home