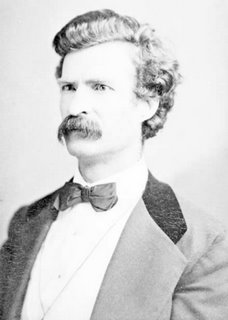

21 April: Boreham on Mark Twain

Laughter and Longing

Laughter and LongingIt would be ungracious to begrudge a thought today to the anniversary of the death of Mark Twain. By a cruel irony of fate, he is known, the world over as a humorist; yet, among all the personal records of the 19th century, there is no life story more deeply tinged with melancholy, or more richly infused with pathos, than is his. Mark Twain's entire career was a desperate fight; he grimly struggled against destiny—and was beaten. Since his death, many books have been written about him, and each of them has made it increasingly clear that he was only a humorist under protest. There was, at any rate in his later life, no gaiety in his soul; he made nonsense to order; he hated having to do it; and he heaved a sigh of ineffable relief when the uncongenial task was finished.

He was a man of passionate affections, and one of his darlings was his daughter, Susy. With the single exception of his wife, Susy knew him better than anyone else; and she has repeatedly assured us that Nature never meant her father to be a funny man. His heart was not in it. He was always more interested in serious subjects than in light ones. His eye sparkled when a discussion was started on some profound and knotty problem; he looked bored when the conversation took a flippant turn. When, at the fireside or the club, his friends gathered about him, they invariably attempted to entice him into entertaining them with clever jest, sparkling witticism, and lively banter; and he seldom disappointed them. But he was obviously relieved when that phase passed and the company settled down to talk on current events, or politics, or even on philosophy or religion.

Beating Against The Bars Of Destiny

He had a natural bent for lofty and serious themes and was angry with the fate that made a clown of him. But what could he do? He was driven to his destiny by a process of elimination. He tried one thing after another, only to be balked by devastating failure. Feeling that he had somehow lost his way in life, he plunged desperately, first this way and then that, only to find himself farther astray than ever. He invented a type-setting machine; he invented a patent food; he invented a cash register; and he invented a spiral hatpin. Into each of these fantastic ventures he poured all his savings. Each in turn was laughed off the market, and each in turn involved him in total loss. Each of these absurdities filled him, first, with delirious enthusiasm, and then with torturing chagrin. He set up as a publisher, and failed again. He therefore yielded to the inevitable. He donned the motley. He would rather have lived his life on a more exalted plane; but he had to make his living, and he found that, by writing grotesque and ridiculous narratives that would set everybody laughing, he could earn more money than he could command in any other way. So, with a fierce rebellion in his heart, he gave the world what it wanted; but, in doing so, he despised himself for his base submission.

One does not like to think that he who radiated happiness in so many millions of homes was himself an unhappy man. It is pitiful to reflect on the author of "A Tramp Abroad" indulging in the most diverting and delicious extravagances and, at the same time, smoking the cheapest cigars and haggling with cabmen about the fare. And certainly we find no pleasure in contemplating him as he lies in bed growling at the universe and dictating his (almost entirely imaginary) autobiography. It is perhaps the duty of charity to conclude that, by this time, his reason had been affected by his numerous disappointments and his heavy losses, and by the gnawing consciousness, that haunted him sleeping and waking, that he was something other than the man that he was meant to be.

A Light That Shone In Secret

In this gloomy sky there is, however, one rift of blue. Mark Twain's wedding day was the golden experience of his life. It opened auspiciously, for, at the breakfast table, a letter was handed to him from his publishers enclosing a cheque for royalties amounting to £800. Later in the day, Mr. Langdon, his prospective father-in-law, presented him with a charming home, beautifully furnished. And the lady who that day became his bride proved the light of his eyes to the last day of her life. In counsel and comfort she never failed him. "Those who saw them together," says an intimate friend, "will never forget the tenderness of that sweet, wistful face raised up to catch every word that fell from the husband with whom her life had been as one from another world." After 34 years of married life, she died in 1904. That, for Mark Twain, was the end of everything. He felt like a man who, from a brilliantly lighted room, emerges suddenly upon a dark and dingy street. He was blinded by the blackness. During the six years that remained to him, the news of an approaching wedding filled him with inexpressible sadness. If the union were marked for unhappiness, he would say, the young people deserved his condolences whilst, if it proved as happy as his own, it must end for bride or bridegroom in supremest tragedy, so that, in either case, sympathy was more fitting than felicitation.

He retained to the end his deep and eager interest in the most majestic and sublime themes. One of the most revealing records of those later days is the record of his insistent search for conclusive evidence of another life. He ransacked all the libraries for books, and more books, and still more books. He read everything that has ever been written on the august theme of man's immortality. Then, thoroughly tired, he laid down the last volume, exclaiming sadly to his housekeeper: "No, I don't believe it! I can't believe it!" "Sir," the good woman replied, "you do believe it! You wouldn't have read all those books unless you did!" Familiar with him as she was, she knew that he was a better man than he gave the outside world to believe. There was a secret spring of satisfaction beneath all his petulance, and a shining hoard of faith behind all his doubt.

F W Boreham

Image: Mark Twain

<< Home