16 April: Boreham on John Franklin

Thridding the Arctic

Thridding the ArcticAustralia in general, and Tasmania in particular, will like to reflect that this is the birthday of Sir John Franklin. The circumstance is of more than passing interest in this State, for with the name and fame of Franklin, Tasmanians feel themselves to be proudly associated. When, in 1843, Sir John laid down his office as Governor of Tasmania, he began to dream romantic dreams of another plunge into the white wastes of the solitary Arctic seas. Most people thought that he had enjoyed his full share of such adventure. Having fought under Nelson at the battle of Copenhagen at the age of fifteen, and again at Trafalgar four years later, he had sandwiched in between these exploits a voyage of exploration with Matthew Flinders in these southern seas—the voyage that established that redoubtable navigator's fame.

The call of the sea was in his blood. In dedicating himself as a boy to a naval career he was simply yielding to forces that he was powerless to resist; and all the fates seemed to smile upon him when they decreed that he should learn the craft of seamanship from the most distinguished masters of all time. Besides serving under Nelson and Flinders, he made friends with the men who had sailed under Capt. Cook, from one of whom, Sir Joseph Banks, he caught the inspiration that sent him cruising into Arctic seas.

Valour That Is Inflamed By Suffering

The ragamuffins in the London streets used to call Franklin "the man who ate his own boots," and he lived to laugh with them at the joke; but it was a grim enough experience at the time. The horror of it invaded his sleep for years afterwards. They were out amidst the snowy vastnesses of the interior when the food failed. They divided into two parties, Franklin leading the stronger men in an attempt to find provisions, whilst Dr. Richardson remained to nurse the more exhausted members of the expedition. The foraging party had no success, and all were reduced to skeletons. Whilst Franklin and his companions were one day resting, Dr. Richardson and a seaman came upon them. They were the only survivors of the group left at the camp. All were soon too feeble to move. In their extremity a herd of reindeer trotted by; but the men were too exhausted to fire. They gnawed at their boots and at anything that promised some appeasement of their devouring hunger. Then, in a thin and wavering voice Franklin led the men in prayer. And this is the next entry in his journal: "Nov. 7, 1821. Praise be unto the Lord! We were this day rejoiced at noon by the appearance of Indians with supplies!" This was in his earlier expedition.

It was on his return to London from Hobart that he undertook the historic adventure with which his name will always be associated. He found, on arrival home, that the Government proposed to seek a way from the Atlantic to the Pacific through polar seas. He begged that he might be made leader of the party. It was objected that he was 60. He indignantly denied it and challenged their lordships of the Admiralty to look up the records. They did; they discovered that he was only 59-and-a-bit; and they gave the appointment! In command of the Erebus and the Terror, he sailed in May, 1845. The two ships were last sighted on July 26, 1845. They then vanished forever. Of the 134 men, not one survived. For many years the whole business was involved in inscrutable and impenetrable mystery. Search expeditions were despatched, first by the Government and afterwards by Lady Franklin. But the fruits of these investigations were pitifully meagre and extremely disappointing.

Disaster Crowned At Last By Triumph

At length, in 1857 Sir Francis McClintock discovered an overturned and dilapidated boat. Underneath it, together with a few guns and watches, he found an assortment of bones and books. Some of these saturated and frozen volumes were once the personal property of Sir John Franklin; indeed, they still bore his name. One of them is a battered copy of Dr. John Todd's "Student's Manual," on almost the last page of which Sir John had underlined the striking text: "Fear not, when thou passest through the waters, I will be with thee." The men whose bones were found with the books had been more than ten years dead. Sir John, it was known from documents found elsewhere, had died on his ship. His last moments were cheered by the knowledge, which arrived in the nick of time, that the expedition had been successful, and that the long-dreamed-of passage had proved a fact.

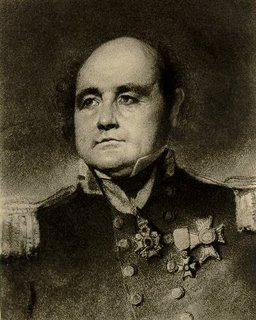

Franklin is described as being a typical navigator. "His features were grave and mild; his stature was below the middle height; his look was kind and his manner very quick, though not without a certain dignity, as of one accustomed to command." He had, Barnett Smith tells us, indomitable courage, endurance, and perseverance, with a buoyancy of spirit and a nobility of soul that endeared him to all who were thrown into contact with him. Few of the monuments at Westminster Abbey hold a more poignant pathos than does the marble that perpetuates the fame of Sir John Franklin. It bears the inscription written by Lord Tennyson:

Not here! The White North hath thy bones, and

thou,

Heroic sailor soul,

Art passing on thy happier voyage now,

Towards no earthly pole.

To this, on Lady Franklin's death, 30 years later, Dean Stanley added a postscript to the effect that the monument was "erected by his widow, who, after long waiting, and sending many in search of him, herself departed to seek him and to find him in the realms of light." Even amidst the chaste and elegant inscriptions that adorn the Abbey, that dual epitaph appeals to most beholders as the perfect tribute.

F W Boreham

Image: John Franklin

<< Home