11 April: Boreham on Charles Reade

A Master of Romance

A Master of RomanceCharles Reade, the anniversary of whose death occurs today, was the youngest child in a family of 11. By the time he appeared on the scene his parents were a trifle tired of the troublesome business of rearing their offspring, with the result that his upbringing was largely entrusted to mentors and preceptors. For some time Charles was confided to the tender mercies of the Rev. Mr. Slattery, of Iffley, who, according to many accounts, might easily have been the original of Mr. Wackford Squeers. Reade's one fond memory of his boyhood was the memory of his mother. To her, he insisted, he owed almost everything. It was while equipping himself at Oxford for a legal career that he made up his mind to devote himself to literature, and quarter of a century later he published "The Cloister and the Hearth," which was not only his masterpiece but destined to take its place as one of the priceless classics of English literature.

Why was it that the hand that was capable of penning so glorious a work gave us nothing else worthy of comparison with it? The sweet, sad love story of Gerard Eliasson and Margaret Brandt stands peerless among the productions of Charles Reade. The rest of his works pale into insignificance beside it. The explanation is that "The Cloister and the Hearth" represents its author's escape from a calamitous infatuation. Charles Reade mistook his calling. To the day of his death he hugged to himself the illusion that he was a heaven-born dramatist. He gave implicit instructions that he was to be described upon his tombstone as a dramatist and novelist, putting the dramatist first. He firmly believed that he was a dramatist by inspiration and a novelistby accident. This unfortunate obsession hampered all his efforts. Some of his novels were first written as plays and were only transmogrified into novels because of failure before the footlights.

Mismanaged Thrills And Sensations

The procedure has obvious drawbacks. It is not easy to produce fiction of delicate artistry out of the second-hand materials of a discarded drama. It is as if a man tried to make a beehive out of an old dog-kennel. It may prove a tolerable and even serviceable beehive, but there will always be something of the dog-kennel about it. As soon as a man has resolved to make, not a dog-kennel but a beehive, he should set himself to make the beehive as little like a dog-kennel as possible. The one huge blemish on the work of Charles Reade is that he proceeded on a diametrically opposite principle. Having made up his mind to write, not plays but novels, he made his novels as much like plays as he possibly could. He exhausts all his energy on the thrills, the sensations, the exciting situations. He is never happy unless a lunatic asylum is in flames, a ship sinking or a bridegroom being foiled at the very altar. He makes you feel that the pages that intervene between these purple patches, are to him, weary wildernesses of arid sand.

With those commonplace paragraphs he has no patience. He often gives you the impression that, knowing what is coming—the highway robbery, the discovery of the vital document, the loss of the nugget or the explosion in the hold—he is in a fever of breathless anxiety to tell you all about it. He is literally sizzling with the tremendous secret. Sometimes his evident perturbation defeats its own ends and you suspect, from his manner, the approaching surprise. Mr. Christie Murray poked fun at Charles Reade's penchant for hurting his sensations at his readers in capital letters. He is so wildly agitated that ordinary type seems a ridiculously feeble vehicle for the conveyance of such an astounding denouement, and he therefore prints in glaring capitals the sentence that, he expects, will take your breath away. But the perverse reader, finding his eye arrested by the huge capitals a page or two ahead of him, reads the too-conspicuous words in advance and is thus deprived of the hair-raising experience that the author had so carefully prepared for his delectation.

A Great And Stately Human

Happily Charles Reade gave us one book so different from the others that it seems to have come from another hand. It is a combination of superb imagination and finished scholarship. The man who has read "The Cloister and the Hearth," carries in his mind for ever afterwards, not a blazing building, a wayside murder or the sensational discovery of buried treasure, but the entire panorama of the variegated life of mediaeval Europe. To peruse it is, as Sir A. Conan Doyle once said, like going through the Middle Ages with a dark lantern. When, 80 years ago, it first made its appearance, its failure seemed assured. It was published as a serial. The Editor grew sick and tired of it before the tale was half told; his candid criticism angered the author and the narrative was discontinued, leaving the climax of the novel to the imagination of the reader.

On reflection Reade himself was inclined to accept that harsh judgment as final, and thought seriously of tossing the immense manuscript into the flames. Even after it had been for some years published he pointed out with evident sadness that, for one person who had read "The Cloister and the Hearth," a hundred had read "It is Never Too Late to Mend." The crucible of time has, however, vindicated the merit of which the general recognition was so tardy and it is on the work that his contemporaries least esteemed that Reade bases his claim to immortality. He was a great human. Gigantic in stature and massive in build, he was vigorous and athletic. The Liverpool cricket ground still cherishes the record of a hectic innings in which he mercilesssly punished one of England's best-known bowlers. Best of all, he genuinely loved his fellow-men. Most of his books were written to abolish the disfigurements and to sweeten the amenities of social life, and, in recognition of this, his work has awakened the gratitude and even excited the affection of all his readers.

F W Boreham

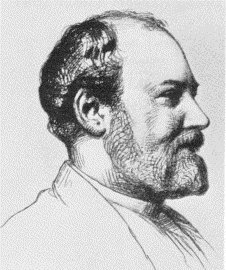

Image: Charles Reade

<< Home