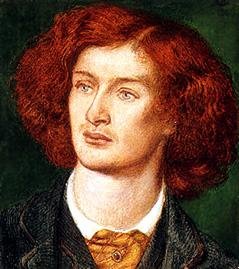

10 April: Algernon Charles Swinburne

A Singer in Revolt

A Singer in RevoltThe anniversary of the death, in 1909, of Algernon Charles Swinburne revives the memory of a state of things that was very familiar to Londoners half a century ago. The scene is easily reconstructed. The great reading room at the British Museum is wrapped in its traditional quiet. The only perceptible sounds are the rustling of the papers, the soft footfall of visitors, and the solemn ticking of the clock. Suddenly, however, the swing door opens and there enter two odd little figures, one of whom horrifies the occupants of the spacious apartment by addressing the other at the top of his loud and raucous voice.

This noisy little nuisance who, being stone deaf, is blissfully ignorant of the enormity of his transgression is Algernon Charles Swinburne, the poet. He is a thin, narrow-chested creature with sloping shoulders and a head slightly reminiscent of Shakespeare, a head that is altogether out of proportion to his diminutive body.

He is grotesquely attired in a disreputable coat, with his trousers so absurdly braced that a generous expanse of white sock intervenes between the extremities of his nether garments and the tops of his boots. The singularity of his appearance is in keeping with his character as a rebel. For Swinburne's entire life and work represent a fierce and relentless revolt.

From the cradle to the grave he was at war with the scheme of things in which he found himself involved. He snapped his fingers at tradition; shook his fist in the face of society; and, like a schoolboy kicking his way through a litter of Autumn leaves, he trampled ruthlessly on all the literary codes and standards that his predecessors had established.

Catching The Spirit Of The Ocean

As a small boy at Eton he raised the flag of rebellion, and one of his verses hints ruefully at the painful consequences:

Alas for those who at nine o'clock

Seek the room of disgraceful doom

To

smart like fun on the flogging block.

In that youthful experience his whole life is reflected as in a cameo. Through all his days Swinburne scorned convention, and, by way of castigation, he writhed under the ostracism and condemnation of an outraged world. Both heredity and environment fed the fires of insurrection in his soul. The son of an admiral, he was reared beside the sea. The wild waters are apt to infect men with their own intractability. Lamartine declares that those who spend their lives within sight of the ocean unconsciously imbibe its restless and unconquerable temper. Swinburne certainly did.

He has told us how the shrieking winds and the turbulent waves moulded the spirit of his childhood. Amid the storm and confusion of the elements, he revelled in the thunder that drowned his voice, in the tumultuous blasts that threw him off his balance, and in the hurricane of flying foam that stung his face and blinded his eyes. He loved to hurl himself into the raging surf and to feel himself hurled about by it in return. It thrilled him with a furious luxury of poignant exuberance and electrified his every nerve.

From such stormy scenes he can block with his ears full of music and his eyes full of dreams. The sea awoke within him the spirit of defiance. In everything that he wrote, and in all that he did, one seems conscious of the influence upon him of those racing and foaming breakers with which he fought and flirted as a boy. They explain him.

Chesterton affirms that, if ever there was an inspired poet, Swinburne was that man. In some respects he attains superexcellence. For stately and majestic diction he is unsurpassable. Many of his most characteristic phrases are arrayed in dazzling splendour, like kings on their way to coronation. Possessing an extraordinary flair for the intrinsic beauty of words, Swinburne revealed the art of a great composer in harmonising and dovetailing rich and tuneful sounds in such a way as to produce the most metrical and lyrical effects. There is an orchestral grandeur about his faultless lines. He was, as Tennyson finely said, a reed through which all things blow into music.

A Serene Sunset Follows A Stormy Day

Like all men, he had his faults. He yielded at times to outbreaks of the most frightful temper, a blemish that disgusted and alienated some of his staunchest and most distinguished friends. As long as their tolerance could endure the strain that his petulance and irascibility imposed upon it, he lived with George Meredith and Gabriel Rosetti at Chelsea. Among his intimates were numbered Burn-Jones, Holman Hunt, John Ruskin, James Whistler, Moncton Milnes, Savage Landor, and Guiseppe Mazzini. They made allowance for his terrible epilepsy and his maddening deafness, and, overlooking his fiery outbursts, saw only the best in him.

When Swinburne was 42—unmarried, tormented by his ill-health, horribly miserable, and prone to seek comfort in alcoholic excess—Theodore Watts-Dunton, the noveliest and literary critic, took him into his own home. And there, for 30 years, the two lived together—"the little old genius and his little old acolyte in their little old villa at Putney." In that riverside suburb, Swinburne became a very familiar figure. He was to be seen every day walking by himself, his deafness rendering companionship embarassing. He noticed nothing and nobody. He was lost in a dream world of apocalyptic vision and glowing inspiration.

Little by little, Mr. Watts-Dunton weaned him from his bondage to his brandy bottle. Towards the end his acerbity grew less pronounced and a certain subtle sweetness occasionally marked his behaviour towards those about him. And, when in 1909, he suddenly died, it was found that he had left all that he possessed to the understanding and sympathetic benefactor who, with beautiful unselfishness, had sheltered his infirmities and solaced his solitude for so long.

F W Boreham

Image: Algernon Charles Swinburne

<< Home