7 April: Boreham on William Wordsworth

A Wartime Singer

A Wartime SingerThis is Wordsworth's day.[1] He was born on the seventh of April. His personality was for all the world like a dazzlingly brilliant gem in a strangely battered and unsightly casket. His forbidding exterior largely explains the blindness of his contemporaries to his inestimable worth. They simply gave him the cold shoulder. It never seems to have occurred to the literary pontiffs of that wealthy period that the gaunt and unattractive figure with stooping shoulders, shambling gait and downcast countenance, haunted the picturesque shores of the English lakes was the natural successor of Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton.

Dorothy, his sister, alone recognised the hidden preciousness that lurked in this shapeless lump of dross. Woman-like, she was in ceaseless distress about his unimpressive contemptible appearance. She was so accustomed to walking by her brother's side that it shocked her when circumstances compelled her to walk behind him. Now and again visitors—a lady and gentleman, perhaps—came to Grasmere. It fell to her lot to attend the lady while her brother strolled on ahead with the gentleman. "Is it possible?" she would ask herself on such occasions, "can that be William? How very mean he looks!" And De Quincey, in telling the story, agrees that she had ample ground for shame. Such a man could not court the smiles of London society. He was only at home in wandering among the rhododendrons on the banks of Rydal Water, or, under the shadow of Nab Scar, declaiming at the top of his voice the latest stanzas that his genius had evolved. Snapping his fingers at ducal drawing-rooms, he paid the inevitable penalty. He snubbed society and society shut him out.

Singing His Blithest Songs While Cannon Roared

He had, however, a message, and he had the artistry to deliver it. He was the prophet of a dramatic age. The terrible and long-drawn-out conflict, which ended with the complete overthrow of Napoleon at Waterloo, lasted with scarcely a break from 1793 to 1815. Those were the identical years during which Wordsworth was writing. In the year of the war he published his first poem; in the year of Wellington's final triumph at Waterloo, Wordsworth gave "The Excursion" to the nation. The analogy is intensely significant. For it reveals the striking fact that a generation almost wholly absorbed in the momentous issues that hung upon the fleets that grappled at Trafalgar, upon the armies that fought at Waterloo, found something singularly satisfying in the poetry of Wordsworth. Yet Wordsworth was not singing battlesongs. He was "the high priest of a Worship of which Nature was the idol."

Wordsworth was more subdued than any of his brilliant contemporaries, but his stillness was the hush that one experiences in treading the aisles of a stately cathedral. The universe is to him a temple; he himself is a white-robed priest serving its hallowed altars. The reverent quietness of the eternal broods over him. He finds in everything, as Dr. Compton Ricketts puts it, a central peace subsisting at the heart of endless agitation. This it was that moved a generation sick of strife to turn its face so wistfully towards him.

From Shelley's dazzling glow or thunderous haze,

From Byron's tempest-anger,

tempest-mirth,

Men turned to thee and found—not blast and blaze

Tumult of

tottering heavens—but peace on earth,

Nor peace that grows by Lethe,

scentless flower.

There in white languors to decline and cease;

But peace

whose names are also rapture, power,

Clear sights and love; for these are

parts of peace.

The Healing And Tonic Value Of Noble Verse

Wordsworth's interpretation of Nature was not so much an exposition of Nature herself as the revelation of something that he had himself discovered lurking behind Nature. "I have learned," he says, "to look on Nature not as the hour of thoughtless youth," but, he adds: I

I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts:

a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is

the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean, and the living air,

And

the blue sky, and in the mind of man;

A motion and a spirit that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all

things.

As a young fellow Matthew Arnold often met Wordsworth at Grasmere and found it difficult to excuse the crudities and oddities that grated painfully upon his own cultured and academic temperament. But such idiosyncrasies could not blind him to the priceless value of Wordsworth's minstrelsy. Time, he wrote,

Time may restore us in his courseWordsworth's healing power! It is a pearl-like phrase and is as true as it is beautiful. It reminds us of Sir William Watson's fine apostrophe. Speaking of Wordsworth, he says that "he gives to weary feet the gift of rest." The exquisite expression is fortified by many concrete testimonies. John Stuart Mill has told us in his autobiography that, in the crisis of his life, Wordsworth acted upon him like a medicine. And more recently, Lord Baldwin has confessed that, on laying down the cares of office after twenty years of incessant strain, he could at first read nothing. Then he turned to Wordsworth’s "Excursion" and afterwards to the "Prelude." "This," he says "braced my mind and did me untold good." This all goes to show that Lord Morley was right when he affirmed that it is the peculiar prerogative of Wordsworth to assuage, to reconcile, to fortify. This is the Wordsworth who must live for ever. With a pitying smile the generations forget the uncouth face, the awkward gait, and the garb. But, forgetting these easily forgettable things, men will remember the lofty notes that, in an age that sorely needed them, the poet so sublimely struck. And, remembering what is so well worth remembering, they will weave grateful garlands of amaranth about the laureate’s honoured name.

Goethe's sage mind and Byron's

force;

But where will Europe's later hour

Again find Wordsworth's healing

power?

F W Boreham

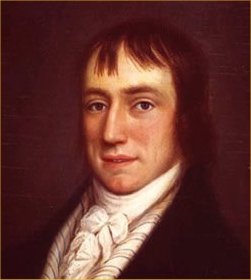

Image: William Wordsworth

[1] This editorial on Wordsworth as a wartime poet appears in the Hobart Mercury on 7 April, 1945.

<< Home