24 April: Boreham on Anthony Trollope

A Wizard of Romance

A Wizard of RomanceThis is the birthday of Anthony Trollope. More than a century has passed since, inspired by the example of his mother, Trollope vowed that he would be a novelist or perish in the attempt. He realised his ambition. The novels that he eventually wrote run into scores of volumes, but in all the fields of fine romance into which his vivid fancy conducts us there is no story half as grotesque, half as pathetic, or half as humorous as the author's autobiography. The life of Trollope is in itself one of the most astonishing, sensational, and stimulating records in the entire realm of biography. Where, except in fiction, is there a narrative of school life so utterly wretched and woebegone as the record of the 12 dismal years that Trollope spent in the public schools of England? He was kicked, cuffed, snubbed, and flogged more, he always believed, than any other human being alive. Five severe thrashings a day represented an ordinary experience; he remembers as many as seven. At the age of 19 he left Harrow without having mastered the multiplication table and unable to write a readable letter.

Perhaps he himself was not altogether to blame, for has history any record of a character so hopelessly shiftless and intolerable as the novelist's father? His ungovernable temper made him the terror of the household. His pitiful incompetence rendered him an object of contempt and disgust in the eyes of all who knew him. He failed at everything to which he set his hand, and on each occasion flattered himself that he could restore his fallen fortunes on a farm. His agricultural ventures only served to make confusion worse confounded. One of Anthony's earliest and clearest memories concerned itself with a certain early morning on which he was awakened at dawn and told to jump up and drive his father to London. He did so, and, after seeing his unhappy parent on the Ostend boat, returned home to find everything in the hands of the bailiff!

Epic Of Feminine Courage And Achievement

Happily that home contains one brighter picture. For where, save in fiction, is there a story of a woman so magnificently unconquerable as Trollope's mother? With her husband and most of her children dying of consumption under her eyes, she set to work to keep the wolf from the door by means of her pen. She left her desk only to tend her patients and left her patients only to resume her work at the desk. She took to literature at the age of fifty-five and published 115 books before dying in her 84th year. The wonder is that the novels were so full of vivacity, sparkle, and charm. They met with immediate success, and by means of the income she received from her publishers she contrived to keep the home together until, one by one, she had committed all her patients to the grave. It was from this really remarkable woman that Trollope inherited his genius.

He himself began dubiously. His first novel was as bleak a failure as a book could very well be. His publisher flatly refused to have anything more to do with him! Nothing daunted, he persisted in writing, and at length coaxed another publisher into issuing his second effort. It, too, proved a melancholy fiasco, and the unfortunate publisher suffered bitterly for his temerity. It was not until he had written four novels that Trollope began to taste the sweets of literary success. His first 12 years of authorship returned him less than £20. Little did he dream in those cheerless days that a time was coming when publishers would pay him £5,000 a year and count themselves fortunate in securing his manuscripts at the price.

A Man Of Affairs Yet A Citizen Of Infinity

He lived to produce more than a hundred volumes, yet the facility of his pen is less astounding than the audacity of his imagination. Take, for example, his own purely fictitious Barsetshire. "I had it all in mind," he tells us, "its roads and its railways, its towns and its villages, its member of Parliament, and the different hunts that rode over it. I knew all the great lords and their castles, the squires and their parks, the rectors and their churches. In all my novels there has been no name given to a fictitious site which does not represent to me a spot of which I knew all the accessories as though I had lived and wandered there." He knew every blade of grass in the Barsetshire fields, and every bird that sang in the Barsetshire hedgerows, although no such place as Barsetshire ever existed! He wrote half-a-dozen novels about bishops, deans, cathedrals, and chapter-houses although it represented a realm of things of which he possessed no personal knowledge.

Happily for his peace of mind, Trollope was never dependent upon these hectic excursions into romance. Entering the Civil Service, he became one of the most honoured and trusted lieutenants of the Postmaster General. To inaugurate improved postal facilities he travelled all over the world, yet all through this strain of official duty he worked with such assiduity at his literary tasks that, at the end of each voyage, he drove straight to his publishers with the manuscripts he had produced on board ship. He and his works will always have a place of their own in the hearts of English-speaking-people. For, as Nathaniel Hawthorne used to say, Trollope is as English as a beefsteak. "Now," he exclaimed, in a message published by his instructions after his death, "I stretch out my hand, and, from the farther shore, I bid adieu to all who have cared to read any of the many books that I have written." A new generation of grateful admirers will gladly grasp that hand today.

F W Boreham

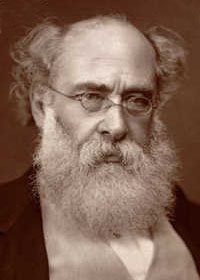

Image: Anthony Trollope

<< Home