5 April: Boreham on Bishop Selwyn

A Master of Men

A Master of MenWhen, more than a hundred years ago, the outbreak of the Maori War was causing widespread apprehension throughout the civilised world, nobody played a more courageous or more creditable part than the youthful Bishop Selwyn, whose birthday we celebrate today. In his "Links in My Life," Commander J. W. Gambier of the British Navy, tells how he met Selwyn in New Zealand in those perilous and difficult days, and he affirms that, beyond a shadow of a doubt, the wisdom and firmness of the young bishop saved the entire white population from massacre at the hands of the infuriated Maoris.

Selwyn was only 32 at the time of his appointment to the see. A new spirit was abroad. It was decided to imperialise the Church. Bishops were to be appointed to evangelise the remotest dependencies of Empire. New Zealand was chosen for the first experiment, and Selwyn was selected as the man. In addition to outstanding gifts of mind and heart, he was a famous athlete. He had rowed in the Oxford-Cambridge university boat race. When he became curate at Windsor, he ventured to visit a certain thoroughfare that enjoyed a particularly unsavoury reputation, A towering giant intercepted him, and, adopting a pugilistic attitude, ordered the clergyman to leave the district. With a skilful blow, Selwyn sent the bully sprawling, and was thereafter treated in the neighbourhood with the most profound respect.

The Man For A Difficult Moment

Selwyn's physical fitness stood him in excellent stead in the distinguished career that followed. Only a man of muscle could undertake the herculean task that awaited him under the Southern Cross. In the nature of the case, much of his Maoriland journeying had to be done on foot. The world has seldom seen such adventurous pilgrimages. He negotiated the most broken and forbidding country with a facility that would have kindled the envy of an engineer. "He was a man of most fascinating and dominating personality," Commander Gambier assures us. "He was a born leader of men. The Maoris adored him and he held them in the palm of his strong hands." The best authorities agree that any dire calamity might have overtaken the infant colony at that critical juncture had it not been for Selwyn's wise, strong, and persuasive statesmanship.

When things were at their worst, and the nerves of all parties were cruelly frayed, the bishop would ask the angry chiefs to meet him. Taking his life in his hand, he would ride to the appointed rendezvous. It was, Gambier says, a truly terrifying spectacle. The frowning chiefs were surrounded by hordes of absolutely naked savages, their eyeballs starting from their sockets, their teeth gnashing and sweat pouring from their dusky bodies, whilst the rhythmic stamp of their feet seemed to shake the very ground. They brandished bloodthirsty weapons, and, above the roar of their hoarse guttural grunts, could be heard the shrill, fiendish screams of their fanatical priests urging them to still more violent exhibitions of fury. But Selwyn confronted them without the slightest manifestation of fear, and, twisting them round his fingers, assuaged their passions and brought them to reason.

Making The Best Use Of A Bad Blunder

His energy was inexhaustible. One would have thought that a country like New Zealand, a thousand miles long, would have been big enough to satisfy the consecrated ambition of any reasonable person. But it was not big enough for Selwyn. In drawing up the Letters Patent of his antipodean see, the crown solicitors had made an astounding and egregious blunder. The area under the young bishop's authority should have been defined as lying between latitudes 34 S. and 50 S. But, by an incredible slip, an "N" was substituted for the first "S." Selwyn noticed the mistake, chuckled inwardly, but said nothing. He saw that the error would make him bishop of the entire Pacific! Later on, when the turmoil in New Zealand brought his work there almost to a standstill, he set out in a schooner of his own to Christianise all these coral reefs and cannibal islands. He recognised, of course, that it would be absurd to attempt missionary work, in the ordinary way among these countless groups. It would take years to acquire the languages, master the customs and overcome the prejudices of the islanders. He determined to resort to strategy. Visiting the various archipelagoes, he took a boy from this island and a boy from that one; he persuaded them to accompany him to New Zealand; and then he bent all his energies to their evangelisation and education. Afterwards, he returned each of these neophites to his native land to spread among his own people the gracious influence of his transfigured life.

And whilst the bishop was lost to sight amidst the multitudinous islands of the South Seas, the leaven that he had hidden in the national life of the Maori people was silently but surely working. During the later phases of the Maori War for example, Gen. Cameron and his men were encamped on the banks of the Waikato. The troops were almost destitute of provisions. The Maoris held a very strong position at Meri-Meri, farther up the river, and an attack was expected at any moment. Suddenly, several large canoes were seen coming round the bend of the stream, and Col. Austin went down to reconnoitre. To his surprise he discovered that, instead of being crowded with fierce and tattooed warriors, the canoes were loaded with milch goats and potatoes! The British officers stared in abject amazement. "We heard," explained the Maoris "that you hungered. The Book says: 'If thine enemy hunger, feed him!' You are our enemies: We feed you: that is all!" And the canoes put off on their return journey to Meri-Meri as though nothing extraordinary had happened. Dr. Selwyn remained in New Zealand until 1867 when, at Queen Victoria's strong personal request, he accepted the historic see of Lichfield where, in a place of great honour in the cathedral, his monument and grave are still to be seen.

F W Boreham

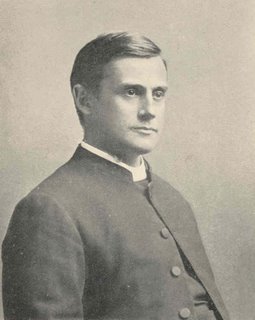

Image: George Augustus Selwyn

<< Home