19 May: Boreham on Nathaniel Hawthorne

Dazzled By The Glare

Dazzled By The GlareIt is exactly a hundred years since Nathaniel Hawthorne, the anniversary of whose death we mark today, having at last established his great reputation, left America for Europe. He is one of the few men who has been blinded by the glare of his own success. His plunge into prominence is a romance in itself. In early manhood he was employed at the Customs House at Salem, Massachusetts. He loathed the place; abhorred the work, and detested everything in any way associated with it. To escape from the hateful memories of the daytime, he gave rein to his fancy during the evening. Thus, he inaugurated his literary career.

As a boy, wandering about the woods, watching the antics of the grey squirrels in the oaktops, gathering blueberries under the pines, or fishing for trout in the little stream near his home, he often pondered the problem of the future. "I do not want to be a doctor and live by men's diseases," he wrote to his mother, "nor a minister to live by their sins, nor a lawyer to live by their quarrels, so I shall have to be an author!" His first efforts, however, met with only meagre success; but he was happy in gaining an ardent admirer in the person of Sophia Peabody, who, in his 39th year, became his wife.

One Door Closes; Another Opens

When, some years later, he lost his position at the Customs House, Sophia matched his dejection by her elation. "Your opportunity has come at last," she cried, "now you can be an author by profession!" Hearing of his plight, Mr. Fields, the publisher, called and seconded Sophia's appeal. Almost as soon as Mr. Fields had left the house, Nathaniel had a brainwave. Seizing a manuscript that he had written in his spare time, he hurried after the publisher. "I wondered," he exclaimed breathlessly, "whether you would look this over. It is either very good or very bad; I don't know which!" Before he went to bed that night, Mr. Fields had made up his mind. He realised that "The Scarlet Letter" represented the most gripping and penetrating drama that the Western world had yet produced. He immediately wrote to Hawthorne in terms so laudatory that the astonished author seriously doubted the publisher's sanity. He thereupon read the tale to Sophia. It reduced her to tears and, to his surprise, he found his own eyes becoming dim, and his voice unsteady.

The basic excellence of Hawthorne lies in his extraordinary capacity for developing a rich vein of psychology without arousing the reader's suspicions. He did what George Eliot did, and did it more delicately. George Eliot confessed that she envied him his skill. He never moralises and never preaches; from the first page to the last the eye of the reader is fascinated by the moving pageant of picturesque objects, quaint personalities, and dramatic happenings. Yet all the time an impression is being created that is only realised after the book has been laid aside.

"The Scarlet Letter" stands in a class by itself. There is no novel in the English language more vivid, more arresting, more affecting. It appears to be only a powerful story, tellingly unfolded; yet, as the reader looks back upon it in meditative retrospect, he sees that it represents the greatest exposition of the potentialities of the human conscience that literature has ever presented to humanity.

Struggle To Recapture Lost Inspiration

He went on writing, but, unlike Browning's wise thrush, he never could recapture his first fine careless rapture. He worried about it. A friend, General Pierce, attributing his depression to failing health, took him away to the Hampshire mountains. But, in losing heart, Hawthorne had lost his hold on life. General Pierce entered his friend's room at their holiday resort one morning only to find that, without any sign of a struggle, Hawthorne had slipped away in his sleep. His taste of fame had been too much for him.

Close to his old home at Concord is the beautiful and secluded little cemetery of Sleepy Hollow. Here, in quiet moments, Hawthorne loved to stroll under the lowering pines. And here, on a perfect Spring day in 1864, he was laid to rest. "We have lost," exclaimed Longfellow, "one of our greatest national adornments. Nothing can compare with the exceeding beauty of his style; it is clear as running waters are." Longfellow lived on for nearly 20 years, but to the last day of his life he always spoke of Hawthorne as one of the most transparently sincere, one of the most delightfully companionable, and one of the most irresistibly magnetic men he had ever known.

F W Boreham

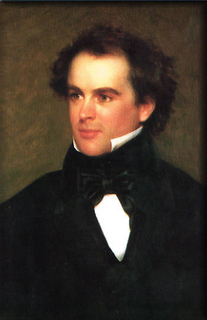

Image: Nathaniel Hawthorne

<< Home