18 May: Boreham on George Meredith

The Light That Failed

The Light That FailedThe anniversary of the death of George Meredith awakens subdued pensive thoughts. It is no secret that he went down to his grave a disappointed man. He felt, and felt keenly, that his literary artistry had failed of adequate appreciation. His conscience assured him that he was an honest workman who had taken extraordinary pains with every sentence that he had framed. Perhaps it would have been better if those ornate phrases had been less laboured. His fastidious selection of unusual words conveyed to the ordinary mind the impression of pedantry and affectation. His vocabulary seemed unnatural, stilted and, at times, a trifle ridiculous. He struggled frantically to charge each pennyworth of language with a pound's worth of meaning. But it was love's labour lost. The sheets would have been more readable if the writer had employed the word that occurred most readily to him. He sacrificed simplicity to exactitude; and excellent as exactitude may be, it is dearly bought when clarity is the price.

Most people associate Meredith, in some vague way, with Browning. Meredith is in prose what Browning is in poetry. The population of the world may be sharply divided into three parts. The first part, representing the vast majority, leaves both Meredith and Browning severely alone. The second part, representing the majority of the minority, reads both Meredith and Browning without pretending to understand either. The third part, representing the minority of the minority, reads both Meredith and Browning with understanding and delight. Compare Meredith with Dickens. We all grow fond of the droll, fantastic, and lovable characters that strut across the pages of Dickens. We echo their odd quips and whimsical utterances, but we never quote the serious opinions of Dickens himself. With Meredith it is vastly different. Nobody makes affectionate, familiar reference to his characters, yet all his readers quote his clever observations. A little girl is credited with having said, in answer to an examination question, that the Arctic regions are useful for purposes of exploration. It is certainly true that Meredith is useful for purposes of citation. His gnarled phraseology and terminological gymnastics lend themselves to that kind of thing, yet only once in a blue moon do we meet with a man who would sit down and, for the sheer joy of it, read Meredith's books.

Novelist Who Stands On His Dignity

There is all the difference in the world between the man who is determined to follow his own bent, whether his own bent happens to accord with the prevailing standards or not, and the man who is resolved, at any cost, to run counter to the popular idea. Meredith was too fond of putting people right if they happened to be wrong and putting them wrong, if they happened to be right. He liked to contradict them, anyway. He gave his plots an unexpected turn, not because the unexpected turn strengthened the plot, but simply because nobody was prepared for such a denouement. He liked to lead you to believe that a story would develop along certain lines for the pure delight of making it develop along quite other lines. And then, with impish mockery, he seemed to come out from behind a bush and laugh at your bewilderment.

It was George Meredith's way of asserting the inviolable rights and prerogatives of George Meredith. He would have you clearly to understand that it is he who is running this business, and not you. He represents things as excellent, not because he really feels them to be excellent, but because the world at large turns up its nose at them. He declares that things are stupid, not because he really believes them to be so, but simply because the popular esteem for these things gets on his nerves and irritates him. To Meredith the public is always very much of a dunderhead. Yet, with all his assumption of independence, it is difficult to acquit Meredith of a charge of affectation. He is seldom perfectly natural. And, oddly enough, his affectation sometimes leads to imitation. In spite of all his swagger about being himself, he became a hero-worshipper; and, as is inevitable, models himself on his heroes. Browning, it has been said, was born with a stammer; Meredith deliberately cultivated that stammer. Later on, he fell under the spell of Carlyle and aped his turgid splendour. But the mimicry proved a misfit. Carlyle's style suited Carlyle's themes, but could even Carlyle have written novels in that billowy manner? Browning's stammer may have suited Browning, although even that is open to question: it certainly did not suit George Meredith. Nor did Carlyle's blast and bluster.

Heart Of Gold In Tortured Setting

There was, however, something very lovable about him. Pitying his deafness and his crippled limbs, Barrie would allow nothing to prevent his going to see George Meredith on his birthdays. Francis Thompson could never speak without emotion of Meredith's goodness to him in the days of his poverty and obscurity. In endeavouring to estimate the value of Meredith, one is tempted to indulge in "ifs" and "might-have-beens." If, at the age of twenty-one, instead of marrying the daughter of Thomas Love Peacock—a marriage fraught with misery for both of them—he could have taken to himself the lady whom he married four years after his first wife's death, when he himself was thirty-six and who filled twenty-one years of his life with sweetness and felicity!

If he could have been spared the horrible disease that, entirely incapacitating him, deprived him, a passionate lover of the open-air, of all out-of-door enjoyments! If, at the very outset, he had shed all his grimaces, artificialities and affectations: if he had said all that he had to say with straightforwardness, naturalness, and simplicity! And if, instead of talking about being himself, he had been himself, saying what he had to say in the first words that came. Had these things come to pass, George Meredith would indisputably have taken his place among the very greatest of English authors. As it is, he has forfeited that honour, and, strangely enough, he owes his loss to blemishes that he himself was noisy in denouncing.

F W Boreham

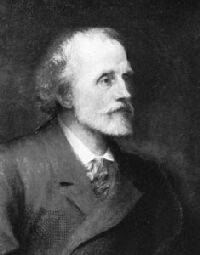

Image: George Meredith

<< Home