16 May: Boreham on Oliver Lodge

Weather to Order

Weather to OrderAmong memoranda left by the late Sir Oliver Lodge were some particularly suggestive notes, dated May 16, concerning our control of the weather. Sir Oliver cherished a conviction that a time is coming in which, instead of tamely submitting to any weather that happens to drift along, we shall deliberately make up our minds as to the kind of weather we want, send in our order, and see to it that delivery is in accordance with instructions. Sir Oliver did not elaborate on details. Though he lived to be nearly 90 he had not time for everything, and this was one of the schemes he had to be content with leaving in bald and general outline. Perhaps if he had become a centenarian he would have celebrated his 100th birthday by presenting humanity with a full account of the project on which his busy and brilliant brain had been so long working. The matter is beset by obvious difficulties. It is notorious that you cannot get weather—or anything else—to please everybody. It often happens that millions of people are longing for sunny skies at a time at which millions of others are fervently praying for rain. The teachers who are planning the picnic, and the women preparing for the garden party, are feverishly anxious for a fine day. The farmers and the gardeners are just as eager for a wet one. Sir Oliver would have brushed aside this little difficulty with a condescending smile. Its triviality would have amused him. He would have told us to set up some authoritative body, representative of all the interests at stake, whose duty it shall be to decide upon the kind of weather that the country really needs. The decisions of that central body will be communicated to the department that arranges for the weather and the sunshine or the showers thus ordered will be promptly and faithfully delivered!

Lure Of The Unknown

Sir Oliver's confident prediction conjures up a state of things that, possessing obvious advantages, is by no means destitute of drawbacks. It will be nice to get exactly the weather that we want. It will be nice, too, to know, with absolute certainty, exactly what weather we're going to get, each change working up punctually, according to the official schedule. And yet, human nature being what it is, we shall all revolt more or less emphatically against this stereoyped, mechanical, cut-and-dried, made-to-order, condition of things. The sporting instinct is tremendously strong in all of us. We like to leave something to chance.

Even children find a piquant pleasure in opening their mouths and shutting their eyes and seeing what grandmother sends them. Half the pleasure of the Christmas stocking arises from the uncertainty as to its contents. We all find it interesting to glance from the window first thing in the morning to see what kind of a day it is likely to be. We feel that we are plunging our hands into Nature's lucky bag. We like to be teased by curiosity and speculation. We love to guess and wonder. The glorious uncertainty of cricket is universally regarded as the greatest charm of the game. Who would wish to see the play if all the issues that now depend on sheer luck were determined by a committee? We find an irresistible fascination in those things in which the main factors are left in the lap of the gods. Applying to cricket and a thousand other things, this principle also applies with special force to the weather for the simple reason that, while most of those things recur but occasionally and fitfully, the weather is a matter of continuous and perennial interest. It concerns each of us all the time. Like the poor, it is always with us. Moreover, the greater includes the less. The elimination of the element of uncertainty in regard to the weather will go a long way towards eliminating the element of uncertainty in regard to cricket and similar games. We shall miss our guessing and hoping and fearing when Sir Oliver Lodge's dream comes true. We shall go to bed at night knowing perfectly well the kind of weather that is being prepared for the following day, and, with the cold and mathematical precision of clockwork, we shall greet those pre-arranged conditions when we throw up our blinds in the morning.

Right To Grumble

And then, what of our ancient prerogative—of which we had rashly supposed nothing could possibly deprive us—of grumbling at the weather? In his "Wild Life in a Southern County," Richard Jefferies declares that farmers are one of the happiest of men, but Jeffries is careful to add that his happiness arises largely from his freedom to grumble. In this respect the farmer represents us all. Especially do we enjoy grumbling at the weather. The psychology of the procedure is interesting—and flattering. When we grumble at the way in which a particular thing is managed, we inferentially suggest our own superiority to the management that we criticise. When we grumble at the weather, we indirectly claim that we could manage it more satisfactorily if it were left to us. When Sir Oliver's dream materialises, this satisfaction will be denied us. We shall still grumble, of course, but at what? At present, when we grumble at the weather, we are in reality grumbling at the universe and asserting our superiority to it. Under the proposed regime, we shall simply be grumbling at the local weather bureau and asserting our superiority to it. It is a somewhat humiliating come down!

Surprises Of Tomorrow

We must, however, take things as they come. The move-on regulation is relentless. We must advance with the times whatever the movement may cost us. Progress invariably exacts payment. A child matures and, in the process of maturing, sacrifices his toys. We must keep an open eye, and an open mind on the developments to which Sir Oliver Lodge has pointed. We have been so long indoctrinated with the idea that if, in the matter of weather, we cannot get what we like, we must like what we get, that it appears at first blush a new and startling heresy to be told that, when we know how to go about it, we shall be able to switch on the sunshine as we switch on the electric light and turn on the rain as we turn on the water at the tap. All this would have sounded to our grandfathers like a sacrilegious invasion of powers and prerogatives with which we have no right to meddle. But we are living in an age of wonders. Nothing now surprises us. Nothing seems inevitable. Science has already done so much to show us that the universe is more intricate, yet more manageable, than our ancestors supposed, that we are now prepared for any sensation she may have up her sleeve. This fresh development should it eventuate, will be but one more step along the enchanted road that has already revealed to us so many marvels. For weal or for woe, humanity has hitched its wagon to a star and to the end of the chapter, must drive that high-mettled and celestial steed.

F W Boreham

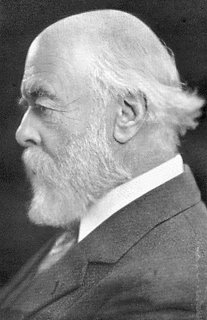

Image: Oliver Lodge

<< Home