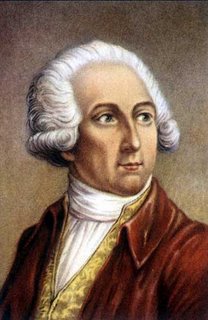

10 May: Boreham on Antoine Lavoisier

Tragedies of Science

Tragedies of ScienceAmidst the raging delirium of the French Revolution, Mme. Defarge and her ghoulish knitting women counted the heads of the wretched victims as they fell from the guillotine. If, going a step farther, Mme. Defarge had possessed the genius to assess the value of those heads, she would have discovered that they contained some of the finest brains in Europe. Antoine Lavoisier, the anniversary of whose death we mark today, is a case in point. With the restless and insatiable curiosity that distinguished such men as Galileo, Newton, Wren, Lister, and his compatriot Pasteur, Lavoisier's hungry mind insisted on finding ever new worlds to conquer, and once he found his world, every continent and island in it had to be penetrated and explored.

A titanic cosmopolite, he made the universe his laboratory. His triumphs were as innumerable as they were sensational. In his researches into the prerogatives and potentialities of earth, air, and water, he gave a new interpretation and a new orientation to the entire material world. He insisted on knowing everything about everything. There was nothing in the heavens above or on the earth beneath that eluded his investigations. As Lalande said of him: "Go where you will, Lavoisier is everywhere." He poked his finger into everybody's pie, not for the gratification of his own palate, but in order to help the housewife to make her next confection still more appetising and with a smaller outlay of labour and material.

New Look For Industry And Commerce

Holding with Bacon that nothing can be too insignificant for the attention of the wisest which is capable of giving satisfaction to the meanest, he applied his powerful intellect to the most mundane and practical affairs. He took for his province every phase of commerce and industry. At the age of 23 he was decorated by the Academy of Sciences for an essay on the best way of lighting the streets of Paris. In order to render his eyes sufficiently sensitive to make the experiments involved in this inquiry, he spent six weeks in a dark room. Turning his attention to agriculture, he took over a farm near Blois, and, in a very short time, doubled its production. Applying himself to gunpowder, he added one third to its explosive force, giving the arms of his country an immediate advantage over those of her prospective enemies.

Eminence, however, has its perils and its penalties. The dazzling successes of Lavoisier excited the jealousy of his rivals. He enjoyed the distinction of having his effigy borne through the streets of Berlin and publicly burned. But his most dangerous foes were those whose faces he saw every day. At the age of 26 he was placed in charge of the Department of Taxation. Later, he became Commissary to the Treasury, and, later still, Minister for Armaments. His handsome figure and charming manners enabled him to add lustre to every office to which he was elevated. He became, whilst still in his prime, one of the most commanding personalities in France.

Greeting The Scaffold With A Smile

This proved fatal. To play any part in French politics at that moment was like taking one's seat on a keg of dynamite. Men like Marat, Danton, and Robespierre were turning the country into a seething cauldron of unrest and insurrection. The consequence was that when the Reign of Terror broke out, Lavoisier constituted himself one of the tall poppies. He was one of the hated aristocrats. Conveniently forgetting that he had been born rich, his enemies alleged that his wealth resulted from the exploitation of the masses and the misappropriation of the taxes.

He was 52 on the day of his arrest, "I have had a fairly long life," he wrote, "and a very happy one. I shall I think, be remembered with regret and I leave some reputation behind me. What more could I ask? I shall be saved the sorrows of old age; I shall die in the possession of all my faculties, and I have the gratification of knowing that my work is done and done as well as I was capable of doing it." For some inscrutable reason, the revolutionists spared his beautiful and talented wife, although they bundled her father on to the tumbril; and for the 42 years that remained to her, she was haunted by the memory of the dreadful moment in which she embraced her husband and father as they were dragged away to execution. And Mme. Defarge, looking on, added two more heads to her tally.

F W Boreham

Image: Antoine Lavoisier

<< Home