23 November: Boreham on Richard Hakluyt

Seed-Plot of Heroism

Seed-Plot of HeroismIt was on November 23, 1616 that there passed away a soft-footed, soft voiced little clergyman who had made history by writing it. Without attracting any notice or making any fuss, Richard Hakluyt did a work that will influence the destinies of men and nations as long as the world endures. It may be questioned whether any one man has done more, directly or indirectly, to put iron into the blood of the British race, than has he. Living in stirring times, the young cleric displayed extraordinary skill in catching their temper, crystallising their genius, perpetuating their splendour and immortalising their fame. England had just awakened with a start to the glory of her destiny. Richard Hakluyt and Walter Raleigh were in their cradles at the same time; and, in the year in which Shakespeare died, the old vicar also slipped away.

The temper of the time was altogether to his taste. The age was moulded to his measure and he was moulded to the measure of the age. A hero-worshipper had been born into an era in which heroes were springing up like mushrooms on a misty morning; and, happily, he stood endowed with exactly that species of talent which enabled him to make the most of so golden an opportunity. As soon as he sat up in his cradle, rubbed his eyes, and took his bearings, he realised that the air was tingling with the spirit of adventure. The centre of imperial gravitation was rapidly shifting from Madrid to London. England was supplanting Spain as mistress of the main. Navigation was the fever of the age. Every young gallant had a constellation of new worlds tucked away among the grey matter of their brain. The high seas were speckled with a snowstorm of white sails. Westward Ho became the universal cry.

Saturated In The Spirit Of A Stirring Time

One after another, there arose men like Sir Humphrey Gilbert, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Francis Drake, Sir Martin Frobisher, Sir Richard Grenville, and Sir John Hawkins. The astounding exploits of these dauntless seadogs held spellbound the attention of the civilised world; and, since the theatre of their operations was so limitless, each of their achievements led to the wildest speculations as to the nature of the feat that should be next acclaimed. The sensation of one day made men excitedly expectant of a still greater thrill the next. This atmosphere, electric with eventfulness, perfectly suited the temperament of Richard Hakluyt. Never was there so striking an example of the way in which inclination conspires with environment in fitting a man for his life work. As a child, Hakluyt was swept off his feet by the prevailing passion of the time. Somebody had shown him a map of the world—a queer old map, compounded of a minimum of geography and a maximum of guesswork. Crude as it was, however, it fired his fancy and implanted in his mind an insatiable hunger for knowledge. And, in order to appease that restless craving, he made himself master of several languages and even acquired the science of navigation.

He loved, whilst still a boy, loitering about the docks, eavesdropping around groups of sailors just home from distant ports, and picking up uncouth scraps of their quaint jargon. He liked to see their bronzed faces and their tattooed arms and chests. He stood spellbound as he watched a tall ship being lashed to the quay, or, in the course of his walk, met mariners, merchants, nobles, and courtiers, hailing from the strange lands of which he had so often read. The spectacle of a sailor coming ashore with a parrot, a monkey, or some such trophy of his overseas adventures, threw him into transports of uncontrollable excitement. Increasingly fascinated by the stories that he gathered in the course of these waterside peregrinations, he resolved to devote his life to the literature of travel.

The Infectious Quality Of Recorded Valour

Fortune favours the brave. From the moment at which he formed this high resolve, circumstances wove themselves into a web that provided him with excellent material for his prodigious undertaking. History, and especially oceanic history, suddenly became sensational. So, the year after the towering galleons of the Armada had been sent to toss with tangle and with shell, he gave the world the first instalment of his monumental "Voyages." This remarkable work, which was published, volume by volume, during the closing decade of the sixteenth century, contained a most graphic, detailed and exact account of no fewer than 220 separate voyages. It is from end to end a glowing epic of adventure. Moreover, it is the massive foundation on which most of the more modern chronicles have been based.

Hakluyt was no hero; he was just a hero worshipper. Yet, if there were no hero worshippers, there would be no heroes. Does not the paean of the hero worshipper, in chanting the praise of his hero, beget the first potentialities of heroism in all who hear him? And does not the hero worshipper who takes the trouble to transmit to posterity his veneration for his idol pass the spirit of heroism, like a flaming torch, from one generation to another? It is the vital principle out of which the shining web of history is spun. An earnest man conveys the fire that burns within his own breast to the pages on his desk, and, just as fire communicated to paper spreads the conflagration to every thing that the paper touches, so the reader who picks up these inspired pages falls under the influence of their radiance and their warmth. How many have become pilgrims through reading the story of Bunyan's pilgrimage? How many have made the greatest of all confessions through reading the Confessions of St. Augustine? How many apostolic acts have been inspired by the Acts of the Apostles? And, by the same token, how many gallant souls have done a brave day's work for England through perusing the "Voyages" written by the sixteenth century rector?

F W Boreham

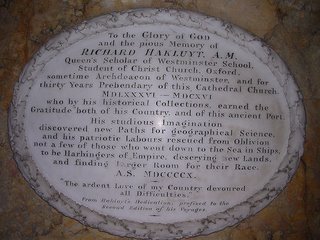

Image: Memorial to Richard Hakluyt in the Bristol Cathedral.

<< Home