15 November:Boreham on William Black

The Paintings of a Penman

The Paintings of a PenmanIt is more than 50 years since William Black, whose birthday this is, passed from us.[1] He died on December 10, 1898. In his day, his vogue was enormous. The lordliest in the land coveted his society and the most gifted paid eloquent tributes to his skill. "That fellow," exclaimed Ruskin, "does things that I could never have attempted, and does them with exquisite artistry and finish." Why, one wonders, has his renown declined? He belonged of right to the first class. Like Hazlitt and Thackeray before him, he cherished a conviction from his earliest years that he was born to be a distinguished painter; indeed, some of the pictures that he produced in those callow days adorned the walls of his home to his dying day. But, as in the cases of Hazlitt and Thackeray, he soon came to feel that he was expressing his art through the wrong medium. He must paint enchanting pictures; but must paint them in another way. He therefore laid aside the palette in favour of the pen.

With his new equipment Black became one of the greatest landscape painters of all time. One can open his works at random, and the page will prove that the writer saw life with the eye of the true artist. "His steel pen," as Sir Wemyss Reid says, "could paint the cloud scenery of a gorgeous sunset, or some fair panorama bathed in the mellow light of noon, with all the rich technique, the fulness of colour, and even the vague suggestions that distinguishes the brush of Turner." Here Black found his metier. He had a genuine flair for loveliness. He had the eye to detect it, the temperament to be thrilled by it, and the high craftsmanship to express it in appropriate forms. In this delicate department of literary excellence, he stands unrivalled.

Specialist In Scenic And Feminine Loveliness

In one other respect Black stands peerless and unique. The unerring skill with which he delineated the magnetic personalities, the varying temperaments, and the sterling characters of pure, noble, and charming women has never been surpassed. Even the Shakespearean women are less convincing and less lovable. Black's heroines swept the country off its feet. Everybody fell head over ears in love with them. Into thousands of homes these sweet and sane and wholesome women—Coquette, Bell, Sheila, and the rest—were welcomed and enthroned as if they had been flesh-and-blood realities. The fondness of the multitudes for the fair creatures of his fancy involved their creator in no small embarrassment. If things went badly with one of these delightful girls, Black was deluged beneath a tidal wave of indignant correspondence. The charm of Black's descriptive work, and the universal affection in which his most engaging characters were enshrined, set all the world wondering as to the personality of Black himself. And, as it happened, that personality was a singularly baffling one.

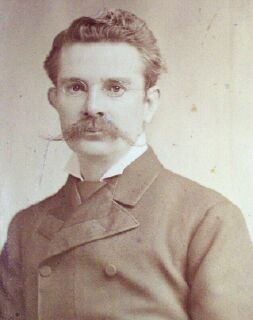

Malcolm Stark has given us the only really convincing description of him that we possess. He seems to have been a thin, dapper little man, very dainty over his dress. His attire was always strictly stylish, yet neat and becoming. He was never seen without spectacles; and, somehow, these contrived to impart to his finely-shaped head an impression of remarkable importance and distinction. He had marked social, as well as intellectual, qualities; and many of the most eminent figures of his time revelled in his companionship. But as a speaker he was absolutely hopeless. When, at a public function, he replied to a toast, nobody could catch a word that he so shyly mumbled. His more intimate friends were never tired of relating the countless engaging peculiarities by which he endeared himself to those who gave him their whole-hearted confidence. He had his oddities, as all such men must have. He would never allow himself, for example, to visit his desk on two successive days. If he had spent Monday on a manuscript, then Tuesday must be given to a long tramp over the south downs, or over the northern moors.

The Poet And Painter Of The Islands

He was often to be seen pacing up and down the old chain pier at Brighton, sometimes in the pouring rain, declaiming to himself dramatic passages that he intended, next day, to commit to paper. He specially loved the islands of the Hebrides and was familiar with every cave and inlet round their rugged coasts. The seafaring men along those splintered and forbidding shores used to say that no pilot was more capable than he of navigating a vessel in those tempest-tossed and mist-enshrouded waters. This was the scenery that he loved to etch; it is the glory of all his books. Nowhere else in our literature can one find such satisfying portrayals of the wild and rocky outline of the northern islands, swept by the storms in which they revel, and battered by the huge breakers whose watery blows seem as welcome to them as a caress. It is amid such scarped and wave-beaten cliffs that his monument has been erected. It stands at the entrance to the Sound of Mull, a few miles south of Duart Castle, on the jagged and beetling coastline that he loved so well.

Black was intensely human; there was always a smile on his face and a twinkle in his eye. He was incessantly talking of some pretty girl to whom he had just been introduced, and of whom he declared himself to be hopelessly enamoured; and whenever he saw children at their play, he could never resist the temptation to drop a few sixpences in order that he might enjoy the satisfaction of seeing the youngsters find them. He was the essence of goodness and purity. Like his illustrious fellow-countrymen, he rejoiced that he had never written a line to unsettle any man's faith, to corrupt any man's principle, or to soil any man's fancy. He died at 57 and was laid to rest at that lovely spot on the Sussex coast that is marked by the grave of Sir Edward Burne-Jones and the home of Rudyard Kipling. If his books are less read than they used to be, it is certainly due to no deficiency either in his artistry or his character.

[1] This editorial appears in the Hobart Mercury on December 10, 1949.

F W Boreham

Image: William Black

<< Home