19 November: Boreham on Abraham Lincoln

A Prince of Presidents

A Prince of PresidentsIt was on November 19, 1863 that Abraham Lincoln delivered, on the battlefield of Gettysburg, the most famous speech of all time, a speech so brief that it is engraved in its entirety on his monument at Washington and yet so perfect that it has come to be universally regarded as a peerless gem of exquisite eloquence. The massive personality of Abraham Lincoln is like a granite boulder torn from a rugged hillside. Too gigantic to be localised, he bursts all the bounds of nationality and takes his place in history as a huge cosmopolite. As Edwin Stanton so finely exclaimed, in announcing that the last breath of the assassinated President had been drawn: "He belongs henceforth to the ages!" With the fine stroke and gesture of a king, he piloted the civilisation of the West through the most volcanic and disturbing crisis of its history, and, in the process established principles which will stand as the landmarks of statecraft as long as the world endures.

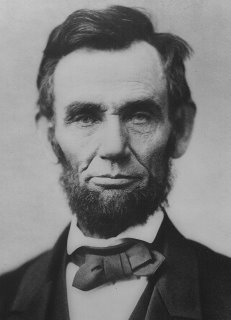

We all seem to have seen him. No face in the pageant of the centuries is better known than his. We are strangely familiar with his six-feet-four of bony awkwardness. At the mere mention of his name, that gawky ill-proportioned form—long arms, long legs, enormous hands and feet—garbed in the clothes that never seem to fit, slouches its uncouth way before our eyes. His coats were the despair of his tailor, and his battered hats nearly broke the heart of his wife. He was an immense human. As Edwin Markham sings:—

The colour of the ground was in him, the red earth;

The smack and tang of elemental things;

The rectitude and patience of the cliff;

The courage of the bird that dares the sea.

Some men are, in themselves, far mightier than their achievements. What they did was great, but what they were is infinitely greater. Abraham Lincoln is the outstanding example of men of this gigantic cast. The world contains millions of people who know little or nothing of American history, and who have but the haziest notions as to the issues at stake in the Civil War, yet upon whose ears the name of Abraham Lincoln falls like an encrusted tradition, like a golden legend, like a brave inspiring song.

To Conquer, He First Conquered Himself

Lincoln contrived to build up an enormous business on a pitifully small capital. One of his greatest claims upon our admiration rests on his phenomenal record of self-culture and self-conquest. He rose on stepping stones of his dead self to higher things. Born in the woods, he had practically no education at all. His mother—his only tutor—died when he was barely nine. Her husband had to make the coffin, dig the grave, and read the service at the burial. Abraham helped him carry that melancholy burden from the desolated cabin to the lonely grave among the trees. Is it any wonder that a boy with such a history should find himself, on the threshold of public life, disfigured by habits and mannerisms that would freeze the blood of the social figureheads of the great cities? During his earlier years his behaviour was shocking. One lady told him frankly that he was never ready with those little gracious acts and courteous attentions which women so highly and so rightly value: but it is fair to Lincoln to add that she admitted, in the next breath, that he was a man with a heart full of kindness and a head full of commonsense.

It is only against this drab background that we can appreciate the real triumph of Lincoln. It is to his everlasting honour that, at an age at which, with most men, character is no longer plastic, he stirred his finer feelings into vigorous activity and proved himself the possessor of knightly qualities that he had always seemed to lack. Awaking to the painful fact that he was boorish, clumsy and unpleasing, he set himself steadfastly to work to remedy these formidable defects. To this severe task he applied himself with such assiduity and such success that he became, in the end, one of the most finished orators of his time, one of the most powerful statesmen that the world has ever seen and the perfect type of the cultured Christian gentleman.

"As The Greatest Are, In His Simplicity Sublime"

Moreover, it is greatly to Lincoln's credit that, rising from such a depth to such a height, he was superbly unspoiled by exaltation. No man was more exquisitely simple, more transparently natural, more utterly unaffected. He put on no airs and assumed no grimaces. He remained to the end, as Mr. Elihu Root said at Westminster, in presenting the Lincoln statue to Great Britain on behalf of the American people, he remained to the end a simple, honest, sincere, unselfish citizen, a man of high courage in action, of great modesty in the hour of victory and of remarkable fortitude in the day of adversity.

He took life seriously, regarding himself as a man with a mission. Indeed, he had two missions—one immediate and one remote. His immediate mission was the preservation in its integrity of the Union, his ultimate and supreme mission was the abolition of slavery. "If ever I get a chance," he had once said in passing a slavemarket, "I'll hit that thing and hit it hard!" The task involved him in dark and trying days. It was feared at times that the agony of the Civil War would unhinge his reason. Happily, he lived to see the sunshine that followed the storm. He saw Peace and Union and Emancipation triumphant. And, with the negroes still singing their rapturous songs of freedom, that "maddest, wickedest bullet ever fired in history" brought his illustrious career to a dramatic and dignified close. He was only 56; but his work was done—done as only he could have done it—and few names in humanity's annals are enshrined in deeper affection, or are more certain of everlasting remembrance, than is his.

F W Boreham

Image: Abraham Lincoln

<< Home