10 November: Boreham on Archibald Geikie

The Secrets of the Stones

The Secrets of the StonesThe cliffs along the coast and the boulders of the quarry seem to guard in impenetrable silence any secrets that they hold; yet one has but to read a record like that of Sir Archibald Geikie, the anniversary of whose death, in 1924, we celebrate today, in order to recognise how garrulous those stones may become. No blare of trumpet or roll of drum marked the centenary of Sir Archibald. Had he died at 50, something might have been made of the great occasion. But the grand old man persisted on his merry and brilliant pilgrimage until he was within hailing distance of his 90th birthday.

As a consequence, everybody felt that it would be a trifle absurd to organise a solemn centenary commemoration in honour of one who had only just vanished from the scenes that he had so conspicuously adorned. Now, however, that we are approaching the hundredth anniversary inauguration of his notable career, we may make amends for the omission of a few years back.[1]

For Sir Archibald Geikie has many claims upon our gratitude. He was easily the most eminent geologist of his time. His patience in research was the admiration alike of his colleagues and of his students. Working among fossils, he never allowed himself to become fossilised. He made it his business to expound his discoveries in such a fashion that street urchins and schoolboys listened spellbound to the story he was telling. To him the rocks unfolded a stirring romance and he held that so thrilling a narrative should be thrillingly told.

There is such a thing, he used to say, as the poetry of dirt. It is the duty of the scientist to recite the stately stanzas of that poem so sympathetically and so musically that every ear shall be charmed by its lilt and melody. Geikie made the study of geology so captivating that he raised up for himself an army of disciples and successors fired by his unquenchable enthusiasm.

Transforming A Hobby Into A Vocation

The secret of Sir Archibald Geikie's resistless authority lay in the fact that he was passionately devoted to his work. His curiosity having been aroused by poking about a quarry near his home—the Witch's Cavern, as he called it—his golden opportunity came to him in his 17th year. Given the option of spending his annual holiday in London or on the isle of Arran, he did not hesitate for a moment. His decision came like a lightning flash. He went to the island; wrote a couple of articles on "Three Weeks in Arran," and thus attracted the attention, first, of Hugh Miller, and, afterwards, of Sir Roderick Murchison. Employed at this time in a lawyer's office, a severe attack of scarlet fever gave him the opportunity of contemplating his career, and, with the advent of convalescence, he bade farewell forever to the legal profession and to his commercial prospects.

He was thus off with old, but was he on with the new? At that stage of the world's history—and of his own— nobody regarded geology as anything more than a hobby or a sideline. Had it anything to offer him to atone for the sacrifice that he had made? To fill in an embarrassing hiatus, the Rev. John Mackinnon invited him to visit the isle of Skye. He went. The natives of Strath beheld with amazement the youth from the city wandering about the island picking up stones and pebbles, tapping them with his hammer, and carefully depositing some of them in the bag that he carried on his shoulder. It was beyond their comprehension. They nicknamed him "The Lad o' the Stanes," and he more than once saw some of the older folk glance knowingly of him, shrug their shoulders to one another, and tap their foreheads pretty much as he tapped the stones. He was wrong in the head, they declared.

Until his 21st year, Geikie himself was half inclined to agree with them. But, just as he came of age, Sir Roderick Murchison asked Hugh Miller if he knew of a young fellow who could be trusted with important work in the Department of the Director-General of the Geological Survey. In his autobiography, Geikie speaks of this as the moment when God took a hand in his life and pointed out the path of destiny. He was appointed to the vacant position; accompanied Sir Roderick Murchison on some of his most notable expeditions to various parts of the Highlands; and from that hour, never looked back.

Common Stones Become Stepping Stones To Fame

It seemed incredible that his fantastic dream of making a living out of the pursuit of his favourite pastime had actually come true. "Who shall describe my delight," he asks, "when that which had been the indulgence of my leisure hours and holiday jaunts became the absorbing occupation of my daily life?" Having set to work early, Geikie early secured recognition. He was only 30 when he was elected to the Royal Society. In 1876, at the age of 41, he wrote a noble volume on geology and sent the manuscript to the Encyclopaedia Britannica. To his surprise, it appeared in its entirety—diagrams and all—in the next edition. Occupying 116 closely printed pages, it is the longest article that has ever been accommodated in that comprehensive literary omnibus.

He was at that time Professor of Geology at Edinburgh University, the idol of his students, and held in the highest esteem by all members of the faculty. Every day his popularity deepened and his renown spread to new realms of conquest. In 1891, at the age of 56, he received the honour of Knighthood, at the suggestion of Lord Salisbury, from the hands of Queen Victoria, who was then midway between her Jubilee and her Diamond Jubilee. Later, on the retirement of Lord Rayleigh from the presidency of the Royal Society, Sir Archibald Geikie was called to that exalted position and thus succeeded to the chair that had been occupied by men like Sir Christopher Wren, Sir Isaac Newton, Sir Humphry Davy, Professor Huxley, Lord Kelvin, and Lord Lister.

In a really extraordinary degree, Geikie commanded the admiring devotion of all with whom he had to do. Men and women alike loved working for him and with him in any capacity. Little children revelled in his society. The last portrait taken of him represents him, at the age of 88, turning the pages of a book with a small boy; he called the picture "Fellow Students." He was then the a grand old Christian gentleman of robust Scottish type; and it is pleasant to reflect that so diligent and conscientious a worker met, all through his long lifetime, with the generous appreciation and resounding applause that he so richly deserved.

[1] This editorial appears in the Hobart Mercury on September 22, 1951.

F W Boreham

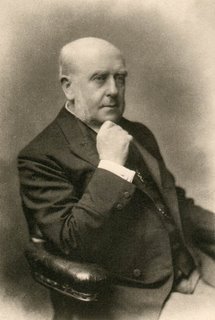

Image: Archibald Geikie

<< Home