31 October: Boreham on John Evelyn

The Triumph of a Busybody

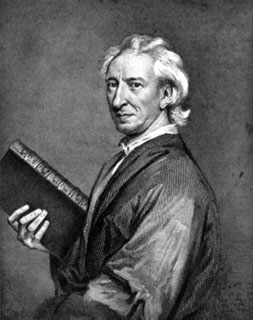

The Triumph of a BusybodyThis dapper little gentleman, pottering about in his beautiful garden at Sayes Court, cocking his head, with its flowing locks, first this way and then that, to make sure that, in pruning his roses, he is making the cut at exactly the right place, is John Evelyn, the greatest diarist of all time, and today happens to be his birthday. It may almost be said that he reached for his diary as he lay sprawling in his cradle and only laid it aside 86 years later when his coffin was brought in. During an extraordinarily adventurous life, in the course of which he went everywhere, met everybody and saw everything, he conscientiously confided to that journal of his, an exact record of his experiences and reflections. In many respects fortune singularly favoured him. Everything seemed to play into his hands. Seeing that he was destined to earn renown as a diarist, he entered the world at the best possible place at the best possible time.

He was born at Wotton, in Surrey, in 1620. It was a moment in world history at which the stage was being set for some of the most dramatic happenings the centuries have seen. In that year Oliver Cromwell came of age and the Mayflower reached New England. If Evelyn had been permitted to choose his birthplace, how could he have improved upon Wotton? Wotton is Arcady, with Babylon just round the corner. You may stand among the greenest of green fields, with the fragrance of the hawthorn in the air and the vesper-song of the birds in your ears, and you may feel that you have left the fevered, thronging world infinitudes behind. But when the sun sinks and twilight falls, the lights of London flare across the sky and you realise that the sylvan glade that had seemed to be at the other end of nowhere is separated only by a sheet of tissue paper from the hub of the universe. The beauty of the Surrey hills—that paradise of Londoners—enfolded the young diarist from his infancy.

Contrasts In Literary Contemporaries

Evelyn was so constituted that both the throbbing life of the adjacent metropolis and the riot of natural loveliness immediately surrounding him made simultaneous appeals to his nature. For he cherished two passions—he loved to watch people and he loved to watch plants. Indeed, by a stroke of genius he converted his fondness for flowers into a magic key that would admit him to the hearts of the people whom he most desired to know. He was remarkably skilful in introducing himself to, and ingratiating himself with, all ranks of society, and he discovered that his familiarity with his garden powerfully assisted him in this respect. Princes and prisoners, statesmen and scavengers, have little in common, but they all love gardens. When Evelyn saw a man with whom he specially desired to converse he would pass a casual but penetrating observation concerning the good man's buttonhole or the floral decorations, and the door he wished to enter swung immediately open.

It takes all kinds of people to make a world. It is difficult to think of John Evelyn without thinking of Izaak Walton. The two men inhabited the same period. In taste and temperament they had much in common, and their souls vibrated day by day to the same tremendous happenings. But turn from the men to their manuscripts and no contrast could be more striking. Evelyn is completely immersed in the spirit of his age. Walton is as completely detached from it. Not many miles from the gabled room in which, seated by the lattice window, the angler writes of the glitter of dew on the speargrass, the notes of the thrush in the blackthorn and the breath of the brier in the hedgerows, John Evelyn bends over the sheets of his diary. And here we have the other side of the picture. For the most part these 2,000 pages of personal impressions conduct us only among courts and crowds. We are in the swirl and the rush and the bustle all the time. We flit from place to place; we leave the drawing-room of my Lady This only to be ushered into the library of my Lord That. We feel the throb and the fever of the exciting period. We hear all the gossip and the tittle-tattle; we pick up every scrap of news and every spicy morsel of rumour. We experience all the thrills attaching to the spectacular and sensational events. We are infected at every turn by the agitations and anxieties of a particularly restless age.

Eyewitness Breaks Silence Of Centuries

Just because of this, Evelyn is the ideal historian. In the diary we are in intimate touch with an eye-witness. The ghastly horrors of the Great Plague and the lurid splendours of the Great Fire have been more elaborately, but never more tellingly, described than in Evelyn's vivid and nervous pages. Through his eyes we seem to see the grim piles of the dead and watch the course of the blazing inferno. In the same graphic and realistic way we witness the dragging of the "carcase" of Cromwell from its tomb at Westminster to be ignominiously hanged at Tyburn. We are painfully present at public executions; we see men put to the torture in the prisons of Paris; we gaze upon amputations and other surgical operations in the days when anaesthetics were unknown; and we watch a very gallant horse baited to death by dogs—for sport! Much of the diary is gruesome, much amusing, much exciting, but it is all interesting and instructive.

It was not until two centuries after the first sheets were penned that it occurred to a firm of publishers that the journal the courtly old royalist had so diligently kept, might merit the scrutiny of other eyes than his own. The dusty bundles of yellow sheets were opened, the faded entries deciphered and, to the delight of a generation very different from his own, Evelyn's colourful and convincing account of life in the days of the Stuarts was at long last presented to the world.

F W Boreham

Image: John Evelyn

<< Home