3 November: Boreham on William Thompson

Overhauling the Universe

Overhauling the UniverseIt was on November 3, 1846 that Lord Kelvin, by delivering his first lecture as Professor of Natural Philosophy at Glasgow University, inaugurated his brilliant public career. At his burial in Westminster Abbey, it was said of Lord Kelvin, that nothing was too simple for his experiment, nothing too abstruse for his powers of calculation. He was no specialist. He took the world for his workshop; he aimed at repairing, reconstructing, or improving everything in it; and, by the time that he laid aside his tools, there were very few activities in life that did not work more smoothly and more effectively because of his skilful touch. Beginning early—he was wrangler of his university at 17, and professor at 22—he was distinguished by a set of rare qualities seldom found in harmonious combination. Never before or since were the theoretical and the practical so perfectly poised in a single personality. His vivid fancy enabled him to visualise the invisible. He saw, as clearly as if he had visited the spot, the inaccessible theatres of operation upon which he bent the powers of his intellect.

When he was grappling with the problems of oceanic telegraphy, the oozy bed of the Atlantic was so clearly before his mind's eye that its hills and its hollows, its geological formations, and its submarine forestry seemed as familiar to him as the leafy lanes around his own home. When he was occupied with the magnetic needle, and was compelled to ponder the illusory centre of gravitation, he talked about the interior of the earth in terms so graphic and convincing that one might almost assume that he had just visited those nether regions. When dealing with the vast infinitudes of space and the astral phenomena of distant worlds, the same principle held good. He seemed to have toured the universe on some magic carpet. He spoke as if he had lived among, and become intimate with, the things that held his thought. Such a faculty, wisely checked and scientifically trained, was an invaluable asset to him. He saw each difficulty at a glance, and, neither minimising nor exaggerating it, was able to consider as though on the spot, the best means of surmounting it.

Hemisphere Talks To Hemisphere

Never was there a man who could be less justly accused of being a mere dreamer. Kelvin ruthlessly submitted each separate idea to the acid test of concrete experience. The vision had to square with reality or it was jettisoned at once. Things had to work or he abandoned them with scorn. He possessed a woman's faculty for seeing what was wanted and for setting his wits to work to contrive some expedient to meet the need. His greatest and most characteristic triumph, although his name is seldom associated with it, was the laying of the trans-Atlantic cable. Lord Kelvin was the heart and soul of this stupendous enterprise. The engineers would, of course, have succeeded sooner or later in laying the cable without any assistance from him; but it is one thing to lay the cable and another thing to get messages along it.

Day after day, Kelvin puzzled over the strictly electrical aspect of the matter until he could tell to a nicety exactly what any fiven current of electricity would do under any one of a thousand different conditions. It was for his work in this connection that he received his knighthood. His experiences at sea opened his eyes to the necessity of improving all kinds of nautical and maritime appliances. The compass then in use had many drawbacks. It was affected by the roll of the ship and by the substances employed in the vessel's construction. Kelvin invented a much more accurate instrument, which, except in minor details, has not since been improved upon. He noticed at once that the method of sounding was both clumsy and laborious, and he invented an appliance for taking soundings with the greatest ease at depths that, until then, could not be measured at all. And he devised a new and more reliable system by which a captain could determine his position.

Sublimity Matched By Simplicity

His adventurous mind scorned all physical limitations. His work covered every branch of intellectual research and he published no fewer than 621 treatises on various scientific subjects. A complete list of his inventions would cover many pages. He was thrice called to the presidency of the Institute of Electrical Engineers. He was made president of the Royal Society, and, during the year in which he held that exalted office, Queen Victoria raised him to the peerage. Like the greatest of the great, he was in his simplicity sublime. Universally revered, no man was more reverent. He was a very great Christian. With all his superb gifts and cyclopaedic knowledge, his faith was the faith of a child. He loved God, loved his Bible, loved his Saviour. When staying with his sister, Mrs. King, in St. John's Wood, the Sunday turned out wet. Church was impossible, and Lord Kelvin suggested, and largely led, a Bible reading. He did more than any other man to show that the Darwinian theory of evolution was not necessarily hostile to religion. "If," he said, "all things originated in a single germ, then that germ contained within it all the marvels of creation—physical, intellectual, and spiritual—that were afterwards evolved." The creation of that germ was as wonderful as the creation, ready-made of the solar system.

All the great European powers heaped their highest honours upon him. When, at the age of 83, he died, he was buried at Westminster Abbey amidst such demonstrations of popular veneration and affection as had never before been accorded to any scientist. "To him," as Principal Russell of Faraday House said, "it has been given to make history which will abide as long as intelligent man survives upon the earth." In the city of Belfast, with which he was closely associated, stands an imposing statue erected to his memory by the proud and grateful citizens. The inscription declares, in words that have always been regarded as singularly felicitous, that Lord Kelvin was pre-eminent in elucidating the laws of Nature and in applying them to the service of man." Lord Balfour used to say that no man in the 19th century exercised upon humanity a more wholesome influence. It would be difficult to conceive of a loftier eulogy.

F W Boreham

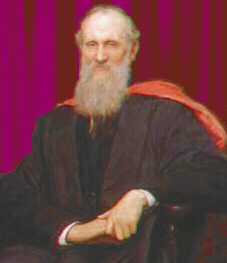

Image: Lord Kelvin (William Thompson)

<< Home