27 October: Boreham on James Cook

The Chivalry of the Seas

The Chivalry of the SeasIn view of the fact that Australia owes him a debt that it can never repay, it is fitting that we should recognise today the birthday of Capt. Cook. His story is one long romance. We are so enamoured of the record of his fruitful voyages of exploration that we are apt to forget that, long before he set out on those memorable enterprises, he had served under Gen. Wolfe at Quebec and had contributed materially in securing the immortal victory on the heights of Abraham. It was, indeed, this adventure, with its characteristic audacity, its brilliant success and its hairbreadth escape that brought the young navigator into prominence and gave him his chance. Until then—and he was already 31—he had enjoyed no educational advantages whatever. In the record of his birth, his father is described as a day labourer, and, in the register containing the entry of the elder man's death, he is still classified in the same modest way. After the notable exploit at Quebec, however, influential admirers took him in hand; he was taught astronomy and the science of navigation; he took to such learning as a fish takes to water; and, soon he won for himself preferment and distinction.

The British are a restless people; they have never earned the philosophy of folded hands. Every great war has been followed by a fruitful era of exploratory adventure. As soon as peace has been declared, the tireless energies of the nation have sought some other outlet. The voyages of Capt. Cook illustrate the operation of this law. For years the nation had been at war. "Never," says Green, "had England played so great a part in the history of mankind." Three of these victories—Rossbach, Plassey and Quebec—changed the face of the world and switched the destinies of humanity into a new channel. Then the long and world-shaking conflict came to an end, and the sword as scarcely in its scabbard when the new national conciousness stirring in the hearts of the British people showed itself in the alacrity with which our seamen penetrated into far-off seas. In the year that followed the Peace of Paris, two British ships were sent on a cruise of discovery to the Straits of Magellan; three years later Capt. Wallis reached the coral reefs of Tahiti; and, later still, Capt. Cook traversed the Pacific from end to end.

Splendour Of Achievement Matched By Motive

In the last book that he wrote, Joseph Conrad enthroned Capt. Cook as the beau ideal among explorers. The most splendid and most exciting adventures in all history, Conrad argues, have been the adventures that have been undertaken from motives nobler than the mere lust of material gain. He confesses to a secret but savage pleasure to the discomfiture of those pertinacious searchers for El Dorado who climbed mountains, pushed through jungles, swam turgid rivers and floundered through malarial bogs without giving a thought to the science of geography.

Over against this, Conrad lauds the fine character and heroic achievements of Capt. Cook. Cook's three voyages, he maintains, are free from any taint of acquisitiveness. His aims need no disguise. They are absolutely and exclusively scientific. His deeds speak for themselves with the masterly simplicity of hard-won success. Cook's own record of his gipsyings—so charmingly modest and so scrupulously exact—stands among the most treasured classics of our literature. Sir John Lubbock included it among the hundred best books in the world. Its influence has been phenomenal. Some of our most eminent travellers, have confessed that they drew their earliest inspiration, and gleaned their most valuable suggestions, from the lucid and illuminating records of Capt. Cook. The modern missionary movement was pioneered by William Carey; but it was the perusal of Capt. Cook's journals that fired his consecrated brain with the sublime idea. The reader who pores over these thrilling pages finds himself in an inevitable quandary. Which is he to admire the more—the qualities that the redoubtable navigator displayed or the ends that he encompassed by means of them?

Master Of Oceans And Master Of People

A tabulated list of Capt. Cook's triumphs takes one's breath away. Apart from his historic work in the long, long wash of Australasian seas, he traversed the Antarctic Ocean again and again, charted a great part of the coast of New Caledonia, explored 3,500 miles of the North American shoreline, discovered the Society Islands and many other groups, and poked his way among the frozen seas of the North Pacific. Nor is this all. For, as Sir Walter Besant has pointed out, his voyages would have been impossible and his discoveries could never have been made but for his researches into the secret of avoiding scurvy.

Yet, splendid as all this is, it is but a revelation of the soul of the man himself. The intrepidity, the humanness, the skill, the sagacity and the sterling commonsense of Capt. Cook will rank, as long as the world stands, as a model for all those—soldiers, explorers, missionaries and the like—who are called to move among indigenous tribes and to handle unfamiliar peoples. It was his character that secured his conquests. His solicitude for his own men, and his tact in dealing with barbarous tribesmen were among the most admirable of his superlative qualities. He came by his tragic death through his insistence on standing between his followers and a horde of infuriated savages. His men escaped; the gallant commander alone fell a victim to the ignorant brutality of the unreasoning blacks. The spot on which he was murdered is marked by a gigantic obelisk and is visited annually by a British warship. Australia, recognising the purity of his superb genius, is dotted with monuments to his deathless fame. The naming after him of the great graving dock is simply the latest of such tributes. Yet, as Sir John Laughton has finely said, his truest and best memorial is the map of the Pacific. He made these seas peculiarly his own, and, in the lands that owe so much to his patriotic daring, his name will always be pronounced in accents that render it not only a priceless memory but an inspiration and a challenge.

F W Boreham

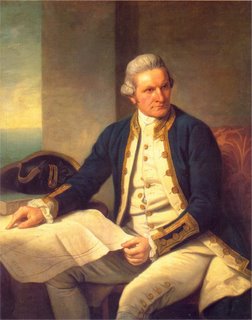

Image: Captain James Cook

<< Home