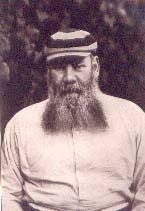

23 October: Boreham on W G Grace

The Elusive Sphere

The Elusive SphereToday marks the anniversary of the death of Dr. W. G. Grace, the greatest cricketer of all time.[1] This suggests an intriguing question. Have we ever done justice to the magnetism of the ball? Harold Begbie says that "England has played at many a game, but ever her toy was a ball." One wonders why. It is easy to understand how such simplicities and trivialities could beguile the infancy of the race; we can imagine crude old cavemen trundling pebbles and boulders to and fro in their elephantine sport; but why, amidst the triumphs of civilisation and the growth of culture, should the ball have maintained, and even increased, its hold upon men's minds? What is there in the ball, on the one hand, and in Man, on the other, to account for the way in which Man and the ball are drawn to each other?

In the entire universe there are only two things worth talking about—Man and his Earth. And what are Man and his Earth but a big Baby playing with big Ball? The processes that we call Science, Agriculture, Commerce, Art, and the rest, are simply the games that the Baby plays with the Ball. Is it surprising, then, that, all life and all history being one colossal ball-game, Man has fallen in love with his toy? Even in his lighter and more leisurely moments, he likes to have some symbol of it constantly before him. Let him play what game he will—marbles, cricket, football, rounders, hockey, golf, tennis, lacrosse, polo, billiards, bowls, croquet, and what not—the elusive sphere is ever the centre of his interest and excitement. The ball has done more than anything else to lure the youth of our race along the path of destiny and achievement. It has toughened their sinews, quickened their minds, and prepared them for tasks that would otherwise have been beyond their powers.

Natural Representation Of Beauty And Life

The pontiffs of the artistic world would probably claim that there is a poetic and aesthetic pleasure arising from the very shape of the ball. It appeals to the eye and the sense as nothing else can do. Art reaches its climax in attractive curves. A curve is the acme of beauty and grace. Why else do painters so delight in delineating the female form? It is simply because the female form presents every conceivable variety of curve and presents that infinite medley of elegant curves in exquisite and harmonious combination. The worst thing that a critic can say about a woman is that she is angular. A ball is richer in curves than the loveliest feminine form, or, for that matter, than any other object whatsoever. It has not the bewildering variety of curves: indeed, it is a perfection of monotony: but what it lacks in diversity, it atones for in quantity. No object on the face of the earth boasts such an innumerable wealth of curves as a ball.

Man is hopelessly in love with life; he like things that display some kind of vivacity or sprightliness or activity or movement. And a ball is the most animate of all inanimate things. A puff of wind will set it in motion; the slightest incline will afford it the opportunity of bounding off on some wild adventure of its own. You seldom find a ball exactly where you left it. Push it or toss it, and it will go a long way without any further propulsion. In the excitement of the game, the ball appears to be a living, sentient thing. It becomes infected by the spirit, and shares the thrills of the hour. It soars through the air, and speeds along the ground, as no other lifeless object can possibly do. It presents an uncanny illusion of actual being; and Man, whose love of life is insatiable, feel the fascination of its apparent liveliness.

The Projection Of Personality Into Infinity

Moreover, Man is a masterful creature. He likes to feel that he is a lord, and that the lower creation exists to do his bidding. A ball, more than any other object of the kind, encourages this consciousness of mastery. It responds to the holder's will. It is more easily caught, more easily held, more easily thrown, and more easily aimed than missiles of any other shape. By means of a ball, a man can project himself considerable distances, working his will upon men and things that he could not personally reach in the same space of time. As he achieves his purpose by means of the ball, the bowler feels that, in its delivery, he is but extending his own personality. The very phraseology of cricket shows how completely the ball absorbs into itself the individuality of the man whose agent it is. We are told that Miller shattered Hutton's stumps, or that Hammond lifted Ellis over the pavilion. In each case, the ball is completely ignored. It is merely the negligible implement by which players express his personality and compass his design.

The medieval philosophers used to say that a ball is the natural emblem of the eternal. Eternity, they argued, is infinitely more than a circle—a thing without beginning and without end. A ball is a globe; and a globe is a circle multiplied indefinitely. There are more circles in a globe than there are stars in the sky, leaves in the forest, or sands on the seashore. The number of circles in a globe is simply incalculable; and, since a circle is the natural emblem of the unimprovable, it follows that a ball is an infinity of perfection. A circle only appears a circle viewed from one angle—immediately above. Lower the eyes, and the circle assumes the form of an oval. Lower the eyes again and it is merely a straight line. But, viewed from any angle, a sphere is a sphere—complete and satisfying. So, said the old teachers, is eternity. It is not only length of life; it is fullness of life. The contrast conveys nothing definite, nothing concrete; yet it emphasises the fact that, just as the sphere is a million million times as great as the circle, so eternity is a million million times as great as any attenuated and emasculated conception that men have ever formed of it.

[1] This editorial appears in the Hobart Mercury on October 22, 1949.

F W Boreham

Image: W G Grace

<< Home