14 October: Boreham on William Penn

A Gentleman's Agreement

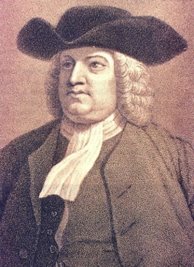

A Gentleman's AgreementWe mark today the anniversary of the birth of one of those vital and dynamic personalities by whom the links between the eastern and western hemispheres were originally forged. Born on October 14, 1644, it was on May 30, 1718, that William Penn, after an extraordinarily colourful and adventurous career, died peacefully in his native land.

In all England there is no more sequestered resting place than the lovely lawn beneath which he sleeps. The grassy spot, surrounded by shady and graceful trees, adjoins the quaintly severe little Quaker meeting house at Jordans, hard by the home of Milton. The tiny headstone bears simply Penn's name, and even this frugal inscription was not placed above the grave until he had slept there for a century and a half.

Yet, although it is embellished by no storied iron or animated bust, no tomb in the land is more honoured than his. For, in troublous times, William Penn made himself a peacemaker of great renown. This fame, wide of the world, is destined to outlive the ages. He who would witness one of the most dramatic and impressive scenes in modern history must turn his attention to the leafy banks of the Delaware. The Algonquin chiefs, a wild and picturesque group, are gathered in solemn conclave. Assembled under the wide-spreading branches of a giant elm, it is easy to see that something altogether unusual is afoot. Ranging themselves in the form of a crescent, these men of scarred limbs and fierce visage fasten their eyes curiously upon a white man who, standing against the bole of the elm, comes to them as white man never came before.

Transition From Bloodshed To Brotherhood

This, of course is William Penn. He is tall, handsome and of commanding presence. His movements are easy, agile, and athletic; his manner is courtly, graceful, and pleasing; his voice, whilst firm and deep, is soft and agreeable; his face inspires instant confidence. He has large lustrous eyes which seem to corroborate and confirm every word that falls from his lips.

These tattooed warriors read him through and through, as they have trained themselves to do, and they feel that they can trust him. In his hand, this man of eight and thirty, girt with a skyblue sash, holds a roll of parchment. And that roll of parchment will stand far all time as one of the most amazing agreements ever completed.

The Indians were accustomed to slaughter. They understood no language but the language of the arrow, the tomahawk, and the scalping knife. The western forests resounded with the war whoops of the Mohawks and the Iroquois. The relations between red men and white men had become tinged with undying hatred and ceaseless hostility. Penn resolved that he would win the Indians by the arts of reason, diplomacy, and friendship.

He succeeded beyond his most sanguine expectations. He ushered in a day in which the red man no longer looked with detestation upon the smoke of a British settlement, and in which the white man no longer dreaded the forests which protected the ambush, and secured the retreat, of his murderous foes. Penn will always be remembered, as Macaulay says, as a ruler who, in his dealings with a savage people, never once abused the strength derived from an ancient civilisation.

An Island Of Peace In An Ocean Of Storm

The treaty made that day was, as Voltaire affirmed, with a spice of pardonable exaggeration, the only treaty ever made without an oath and the only treaty that never was broken. It was adorned, as Bancroft put it, by no signatures and no seals. The sun, the river, and the great silent forest were the only witnesses. Yet no covenant ever made created a deeper impression. Long afterwards, Bancroft adds, the simple sons of the wilderness, squatting in their wigwams, showed their children records of their own, made on shells and bark and wampum, which revived the memory of the wise words of the great William Penn.

The world laughed at the fantastic instrument; but it noticed at the same time that when the neighbouring colonies were being drenched in blood and decimated by the barbarity of the Mohicans, and the Choctaws, the hearths of Pennsylvania enjoyed an undisturbed repose.

Nor was the conquest merely negative. When, after a few years, the followers of Penn began to swarm across the Atlantic to people the new settlement, they were confronted by experiences such as await all pioneers in young colonies. In times of stress, privation, and hardship, even delicate women undertook tasks for which their slender frames were far too frail. In that dark hour, the Indians came to the rescue. The red men worked for them, trapped for them, hunted for them, and served them in a thousand ways.

When Penn himself visited them, they overwhelmed him with the hospitalities. The fields and forests were ransacked to provide provender for the banquet. And when, in 1718, they heard to their unutterable grief that he had passed, they sent his widow a characteristic message of sympathy accompanied by the most beautiful furs. "These," they said, "are to protect you whilst passing through the thorny wilderness without your guide." In the Western world, no name is held in more grateful reverence than that of William Penn.

F W Boreham

Image: William Penn

<< Home