10 October: Boreham on Hugh Miller

The Story of the Stones

The Story of the StonesThis is the birthday of Hugh Miller, the renowned geologist. He richly deserves to be remembered. One can understand how, by titanic force of character and indomitable perseverance, a boy enjoying no educational advantages can achieve outstanding success as a merchant prince, a captain of industry, a naval or military commander, or even as a Cabinet Minister; but the dizziest pinnacle of such personal triumphs is attained when a youth so handicapped becomes a shining luminary in the academic firmament, eventually rising to eminence as a distinguished scientist. Yet, in the first half of the 19th century, that amazing feat was simultaneously performed by Michael Faraday in England and by Hugh Miller in Scotland.

The son of a sailor who sailed his own sloop, Hugh Miller's earliest memory was the memory of that dark day on which, in his fifth year, his mother told him as well as she could through her tears that the little ship had been lost at sea and that he could never hope to see his father again. His two uncles, a saddler and a carpenter, solemnly impressed upon Hugh's infant mind the necessity of applying himself with exemplary diligence to his lessons at the village school; but the boy, always independent and self-willed, had ideas of his own on that subject. He was consumed by two resistless passions—a passion for the open air and a passion for setting down in black and white all that he found among the hills and the valleys around him. His love of the open air made him an incorrigible truant. He recorded all that he observed in the course of his gipsyings with such exquisite simplicity, such absolute fidelity, and such natural charm that those to whom his mother surreptitiously exhibited his scribblings marvelled alike at the objects that he deemed worthy of description and at the grace of the diction with which his artless story was told.

A Hungry Mind Finds Treasure Everywhere

When the time came for him to leave the little school that he had treated with such scant respect, his uncles and his mother agreed that there was nothing for it but for him to earn his living by manual labour. They informed Hugh that they had arranged for him to work in a quarry. The boy's soul died within him. He felt like one who has just been sentenced to penal servitude for life. "I have rarely had a heavier heart," he confessed many years afterwards, "than at that moment." On recovering from the cruel shock with which this announcement smote him, he suddenly remembered one factor in the gloomy situation that greatly solaced him. During the severity of a Scottish Winter, work in a quarry is impossible. This enforced spell of unemployment would afford him the opportunity of cultivating his friendship with his pen.

The drabness of Miller's Youth was illumined by two sensational discoveries. The one was made in the home, the other in the quarry. Having learned to read, largely by puzzling out the notices that adorned hoardings and shop windows, he was advised to apply himself to the Bible. He did so, and had only turned a few pages when he came upon a narrative that swept him completely off his feet. It was the story of Joseph. He could scarcely believe his eyes. "Was there ever such a discovery made before?" he asks. "I had found out for myself that the art of reading is the art of finding stories in books. From that moment, reading became my most delightful amusement." At every spare moment he crept away into some quiet corner with a book. Having exhausted the stories of Samson and David and Elijah, and learned almost by heart the parables of the New Testament, he passed on to Robinson Crusoe, the Arabian Nights and Gulliver's Travels. Eventually he decided to model his own style on Goldsmith and Addison.

Apparent Slavery Opens Gates Of Destiny

Submitting himself, at the behest of his uncles, to the tyranny of the quarry, there came to him, to his unbounded surprise, an experience that filled his mind with immoderate excitement and delight. After some blasting had been done, the boy searched the debris brought down by the explosion. Among the splintered stones and tangled bushes, he found two dead birds of beautiful plumage. His interest now thoroughly aroused, he picked up a nodular mass of blue limestone, and, by a tap with a hammer, laid it open on the palm of his hand. "Wonderful to relate," he writes, "it contained a handsome finished piece of sculpture—one of the volutes, apparently, of an Ionic capital. He broke open other nodules and found surprising treasures. His fancy was thoroughly fired. He had discovered a realm of rare enchantment. And so Hugh Miller set out along the road that made him one of the most eminent geologists of his day.

There was no other course open to him. "Having found such pleasure among rocks and in caves, how," he asks, "could I avoid being a geologist?" He had, of course, other interests. Moved by his recollection of his boyish fondness for his Bible, and inspired by his friendship with men like Dr. Chalmers, he became one of the pillars of the Church in Scotland. Becoming engaged to Miss Lydia Fraser, she advised him to attempt the conquest of those realms of learning that, as a boy, he had neglected. He thereupon applied himself to his studies with such concentration that he became a bank accountant at Linlithgow. But the stones and the strata held all his heart. He pursued his geological researches with such thoroughness that masters like Murchison and Agassiz were grateful for his guidance. In swift succession he published volume after volume, each marked by rare scientific penetration and great literary beauty. Then, unhappily, his story ended in tragedy. His brain collapsing under the strain, he died by his own hand at Christmas-time 1856. He was only 54, but he had lived a life and done a work that will always be treasured as a proud record and an abiding inspiration.

F W Boreham

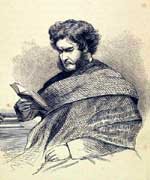

Image: Hugh Miller

<< Home