8 October: Boreham on Henry Fielding

The Founder of Fiction

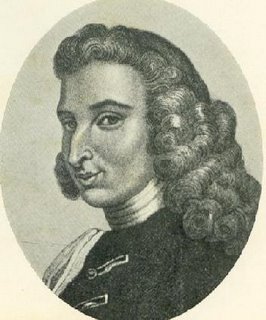

The Founder of FictionWhen, as little more than a boy, Henry Fielding—the anniversary of whose death we mark today—made his way to London in quest of literary renown, he cut a striking figure there.[1] Standing well over six feet in height, he was handsome, lithe, and athletic; his dark eyes flashed with merriment and purpose; his face, save for the aggressive Roman nose, was attractive, well-chiselled and emphatically masculine; his whole appearance conveyed a subtle impression of grandeur and nobility. If, on the one hand, he was disappointed at discovering that, for him, the streets were not paved with gold, he must, on the other, have been gratified at finding that his magnetic personality quickly won for him a host of influential friends.

From infancy he had cherished the proud conviction that he had it in him to write as no man had ever written before. It is one thing, however, to dream dreams; it is quite another to translate them into concrete reality. And Fielding's childhood had scarcely fitted him for that stern task. There is no greater hardship than to be reared like a prince, and then, like a pauper, to be thrown, penniless, upon an inhospitable world. As a boy, Fielding was petted, pampered, and spoiled. He was sent to the best schools, and, at Eton, was a companion of the elder Pitt. Then, his mother having died, his father married again; he found himself very much in the way; and, too proud to live on the bounty of those who preferred his room to his company, he set out to carve for himself a career.

Purpose Held Midst Fortune's Smiles And Frowns

Desperately in need of cash, he wrote, as soon as he came of age, a five-act comedy entitled: "Love in Several Masques." To his unbounded astonishment and delight, it immediately found favour with the management at Drury Lane. This was followed by other successes, but playwriting in those days made no man opulent. His triumphs piqued his ill pride, but put little into his pocket. Like a cornered rat, he darted in various directions, frantically hoping, by this expedient, or by that one, to avert the anguish and humiliation of starvation. The devastating fact gradually broke upon him that he was unable, by the utmost exercise of his genius, to pay his tradesmen's bills. He was nearly 30 when the tide turned. Inheriting a property worth about £200 a year, he married a young lady who added £1,500 to his possessions. Excited by his new sense of wealth, Fielding fancied himself a millionaire; indulged in horses and hounds, and engaged an army of liveried servants. He soon, of course, exhausted his resources and had again to go cap-in-hand to the authorities in eager quest of remunerative employment.

Yet, through all these misadventures and misfortunes, Fielding held true to his boyish aspiration. He made secret opportunities of writing works that, little as he suspected it at the time, will live as long as the language endures. Somebody has said that most of his writing was inscribed, like Francis Thompson's poems, on scraps of tobacco paper and similar tags and tatters. It may not have been as bad as that. But certainly he filled up every odd minute—on the road, in the village inn, in waiting rooms, and in a thousand other unpromising places—in penning the classics that have cast a deathless lustre about his name. It is true that he is not widely read today, and perhaps it is just as well. His work is, to say the least of it, coarse. Not that he himself was indelicate; but he lived in a rude age, and his writings form a mirror in which the temper of the time is accurately reflected. In a sense, one cannot condemn him. When he depicts vice, he depicts it as vice. It is never made to appear gallant, courtly, attractive, or even funny. In his pages, as Lowell has pointed out, immorality is always disgusting, evil is always nauseous.

The Seed That Now Flourishes In Many Gardens

If, however, Fielding is not nowadays read directly, he is read indirectly. His influence has permeated the entire realm of fiction. Just as Richardson introduced the element of sentiment into the English novel, so Fielding introduced the element of humour. From his time to our own, no writer of any note has failed to profit by so illuminating an example. Even Dickens and Thackeray found in the pages of Fielding the suggestions for many of their most grotesque situations and many of their most droll and ludicrous characters. Mrs. Gamp, it is admitted, is but a glorified edition of Mrs. Slipslop. Half the artistry of Fielding lies in restraint. He did not believe in unadulterated virtue or unmitigated vice. He found men very much of a mixture and he so depicts them. His heroes are speckled by grievous faults whilst his villains occasionally astound us by their genuine goodness of heart. Weaving this interpretation of humanity into his work, he has given us some of the most convincing flesh-and-blood characters in our literature.

The pity of it is that his fiery intensity and ceaseless industry wore him down. He was exhausted at forty. At the age of 46, a complete wreck, having to be lifted into the carriage, and on to the ship, he fled to Spain in search of health. It was too late; he died soon after his arrival. Nothing that he ever wrote is more pathetic than the record of his farewell to his native land. When, eighty years afterwards, Sir Walter Scott set out for Italy in similar circumstances, the thought of Fielding haunted his fancy all the way. Fielding lies buried in the English cemetery at Lisbon in a spot surrounded by cypresses—"a leafy spot where the nightingales fill the air with song." All our most eminent writers have chanted his praise. He maintained a brave struggle with the wolf always near the door. For his huge six-volume masterpiece he received but £600. Quite recently his signature was sold in London for twice that sum. The circumstance is not without its poignancy, but it at least shows that, if recognition came slowly, it came surely. Fielding's successors, to atone for the neglect of his contemporaries, have crowned him with laurels that will not quickly fade.

F W Boreham

[1] This editorial appears in the Hobart Mercury on October 7, 1944.

Image: Henry Fielding

<< Home