5 July: Boreham on George Borrow

The Gentleman Gipsy

The Gentleman GipsyGeorge Borrow, whose birthday this is, was essentially a wayfarer, a nomad, a vagabond. He belonged to the open air. On all the winding roads and dusty lanes of England his striking figure was familiar. He was one of the tallest and strongest men in the country, robust, self-willed, sinewy, and athletic. Even in old age he loved to break the ice on a country pond in order that he might enjoy his morning plunge. Nature fashioned Borrow, as one of his friends observed, in a moment of reckless magnificence. He loved to be called the Gentleman Gipsy; and, true to the gipsy type, he developed quite another side to his singular make-up. For, like the gipsies, he occasionally lapsed into a brooding humour so profound that, while it lasted, he was reduced to a condition of the most pitiable melancholy.

Even as a small boy, he descended at times into mysterious abysses of black but silent gloom. He once referred to himself as a deep and dark lagoon, shaded by sombre pines, cypresses and yews. At such periods he hated company, loved to mope in shady nooks and quiet corners, and endured those agonies of spiritual dereliction that stand reflected in the experiences of some of the characters in his books. Somebody has incisively observed that George Borrow is Gil Blas with an infusion of John Bunyan. The two aspects of his contradictory personality will alone explain this odd admixture.

Fame Proves Perfidious But Penitent

Just as there were these two George Borrows, so to him came the unique experience of having twice achieved fame—once during his lifetime and once afterwards. About the middle of the 19th Century, when his books were appearing in fairly rapid succession, fame came to him the first time. Everybody was reading Borrow and everybody was discussing him. The newspapers were full of personal references and quotations; his exciting adventures were the commonplaces of casual conversation. For ten years no writer was more popular or more widely read than the author of the famous travel stories. Thus fame came, but she did not come to stay. To Borrow's unutterable chagrin, she left him, and, during his lifetime, never returned. His later books—the books that are now numbered among our classics—fell flat and failed to awaken the slightest enthusiasm. Borrow was stung to the quick. His sensitive and temperamental spirit sustained a wound from which it never recovered.

He died in 1881, quite forgotten. The Press scarcely contained a reference to his passing. But, as the years have come and gone, fame has relented. In order to offer some kind of amende honorable, she has crept to Borrow's tomb and placed a garland of immortelles there. Some of the most eminent critics of the past half-century—Mr. Augustine Birrell among the number—have saluted Borrow as among the greatest of the great. Such tributes, and their number is legion, go to show that when, in deep contrition, fame returned to Borrow, she came for good.

The Charm Of Unconventional Simplicity

Borrow is utterly destitute of technique. He is easily the least literary of all litterateurs. He was never a bookman. Up to the time at which he published his first work, he had only read his Bible, his Shakespeare, and "Robinson Crusoe." As against this, however, he had an insatiable appetite for languages. At school, everything else was an intolerable boredom to him, and, more than once, he shook the dust of the classroom from his feet, escaped under cover of night, and set out along the great open highway. But he could learn a foreign tongue whilst another boy was thinking about it. At the age of 18 he could speak 12 languages fluently, and could think in the language in which he happened to be speaking. He was articled to a Norwich solicitor; but when, in 1824 on the sudden death of his father, he realised that he was master of his own destiny, he tied together a few foreign translations that had beguiled his leisure, jumped on to a London coach, and took his chance as to what the future held in store. He tramped through Europe, and brought Europe back to London with him. He reduced a continent to manuscript. He wandered through France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Hungary, Turkey, Russia, and the East, not as other travellers had done, but in a fashion peculiarly his own. He trudged along the byways, chatted with everybody, and forgot nothing that he saw or heard.

Then, with an artlessness that is the highest art, he communicated these unconventional experiences to his manuscripts. He does it with such exquisite simplicity and perfect naturalness that we all seem to have seen what he saw and to have met the quaint characters with whom he gossiped by the side of the road. He toured the Peninsula as the agent of the British and Foreign Bible Society: it led him to write his "Bible in Spain": and thus our literature welcomed a new classic. Borrow's travel tales are like nothing else in the language. By means of them he poured into paper his rugged and volcanic personality. N. E. Henley, the friend of Stevenson, used to say that Borrow was as circumstantial as Defoe, and as rich in combinations as Le Sage. "Moreover," Henley added, "he has such an instinct for the picturesque, both personal and local, as neither of them possessed. This strange, wild man holds on his strange, wild way and leads you captive to the very end." It is difficult to account for the way in which Borrow's own generation turned away and left him, especially as it was the distinguishing feature of the 19th Century that its great writers quickly won the recognition of their contemporaries. Borrow, unhappily, is the exception. It is gratifying, however, to reflect on the popularity that his work has since enjoyed; and as long as men love the open air, with its freshness, its romance, and its surprise, there will always be a place in our hearts and in our libraries for the intriguing volumes that Borrow has bequeathed to us.

F W Boreham

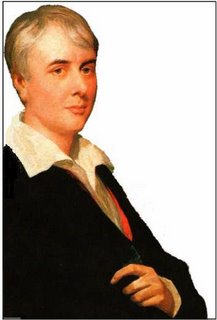

Image: George Borrow

<< Home