4 July: Boreham on Samuel Richardson

A Master of Hearts

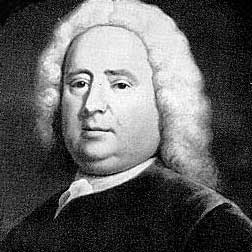

A Master of HeartsThe anniversary of the death of Samuel Richardson reminds us that the man who first suffused literature with sentiment was, to all outward appearance, anything but a sentimental man. He was short and stocky, inclined to be corpulent, exhibiting the easy luxury of a very florid countenance and a pronounced double chin. Some writers describe him as tubby, others as flabby; and both phrases help us to see the man. Wearing a claret-coloured coat and a flaxen wig, he walks slowly—perhaps a trifle pompously—his right hand tucked into the ample folds of his coat; and, glancing quickly about him with slow and placid movements of his heavy head and steel grey eyes, he conveys a subtle impression of kindly benignity, slightly tinged with conscious superiority. He is entitled to a certain measure of self-satisfaction, for he is immensely popular, especially with the ladies—and he knows it.

It is very difficult for us to understand the extraordinary vogue that "Pamela" and "Clarissa" once enjoyed. The ebb and flow of their fortunes were discussed in inns, coaches, chimney-corners, coffee-houses—wherever English people met—while the man who possessed the genius to conceive such stories, and the skill to execute them, was regarded in the light of a national hero. Sir John Herschel has told us how, at Slough, the blacksmith gathered the villagers round the fire in the forge evening by evening and, perched astride the anvil, read "Pamela" aloud to them; and, when they were assured of the triumph and marriage of the virtuous heroine, they were so transported with delight that they rushed pell-mell from the smithy to the church and set the belfry pealing.

A Novelist Gathers Romance At Its Source

Herschel's story is matched by the description which Macaulay gave to Thackeray of the sensation created by "Clarissa" on its arrival in India. "You haven't read Clarissa!" exclaimed Macaulay, in his enthusiastic way. My dear Thackeray, if you once start it, you simply can't leave it!" He told of a hot season that he spent in the Himalayas. The Viceroy of India, the Commander-in-Chief, and other dignitaries were there with their wives. "I had 'Clarissa' with me, the whole eight volumes," Macaulay continued. "As soon as they began to read, they were all in a passion of excitement about Clarissa and her scoundrelly Lovelace. The Viceroy's wife seized the book; the secretary waited for it; the Chief Justice could not read it for tears." Excitedly pacing the Atheneum Library, Macaulay vividly described the scene to Thackeray, chuckling with infinite relish over the memory of the way in which the members of the lordly party feverishly awaited the chance of snatching from one another the volumes that they wanted.

Richardson's initial success was achieved almost before he was aware of it. In the middle of the 18th century a considerable proportion of the population could not read, hence the popularity of the crude entertainment in the smithy at Slough. Similarly, great numbers of people could not write. But there come times when even the most illiterate long to express their thoughts on paper. In Richardson's day there were hundreds of girls who spent half their time wishing that they could write love letters. Here in 1702, is little Susie Smith, a housemaid at the Manor House. Weeping bitterly, she can find no ray of comfort until she confides her distress to the sympathetic ear of her bosom friend, Betty Brown, the chambermaid at the rectory. "I have a letter," she sobs, "and I'm sure it's a love letter but I can't even read it!" "Don't be silly," replies Betty, "take it round to Sam Richardson! He reads all mine to me and writes the most lovely answers!" Richardson was then a boy of 13. To him these damsels thronged. It was essential that each, in order that he might know exactly in what tone to couch her epistle, should tell him with perfect frankness all that was in her heart. Thus he instituted a kind of amatory confessional. The girls gave him their utmost confidence, and he wrote the letter that reflected the languor or the ardour of their sentiments.

Sentiment Plays A Dominant Part In Life

Is it any wonder that, educated in such a school, he became phenomenally proficient in the ways of women? They themselves taught him. Whenever, in the days of his renown, he was asked how he acquired such a penetrating comprehension of the most intricate twists and turns of feminine feeling and feminine thought, he invariably attributed his skill to the lessons he learned at the hands of the lovelorn maidens whose sighs he had reduced to writing as a boy. It was the aptitude that he thus gained for expressing the most passionate impulses of the human heart in the form of letters, that led him to adopt the epistolary style in his novels.

He began "Pamela" in the Winter of 1739. He imagined that the work would occupy several years. But he formed the habit, when sitting by the fire of an evening with his wife and her young woman friend, of reading to them the sheets he had written during the day. This practice awoke their curiosity and intensified his own enthusiasm. Every night, as soon as they drew their chairs to the fire, they would demand the latest news of Pamela. The discussions that followed, and the ideas suggested, lent wings to his quill, and, to his own astonishment, he completed the manuscript in a couple of months.

He proved that love is human rather than aristocratic; heroes and heroines are not confined to courts and castles; the sweetest sentiment may subsist with lowliness and even with poverty. He showed teachers and barristers and clergymen that high words can be served at times by bringing a lump to the throat and a tear to the eye. And, as a result, some of the noblest minds that Europe has produced—Goethe among the number—have confessed that it was at Richardson's feet that they learned the craft of which they became masters.

F W Boreham

Image: Samuel Richardson

<< Home