3 July: Boreham on John Patteson

An Epic of the Islands

An Epic of the IslandsIt was on July 3, 1855 that John Coleridge Patteson sighted the coast of New Zealand and thus inaugurated that heroic career of island adventure which culminated in the most triumphant tragedy in missionary anals. The march of civilisation has been adorned by few more gallant, knightly, or adventurous figures than that of John Coleridge Patteson. Patteson had the ball at his feet from the start. The son of Sir John Patteson, an eminent judge, he was the grand-nephew of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the poet. Delicately nurtured in one of England's stateliest homes, he was educated first at Eton and then at Oxford, enjoying every advantage that wealth and solicitude could cure for him. Vivacious, high-spirited, and athletic, he made the most of these priceless opportunities. In addition to his triumphs in the classroom, he soon became captain of the Eton eleven, and, in historic contests at Lord's, covered himself with glory in many a match.

The times were made for him and he seemed made to match the stirring temper of the time. The eyes of men were being turned to the ends of the earth. Infected by this aggressive mood, the Church of England resolved upon a forward policy. The Church must be imperialised. Bishops must be appointed to evangelise the most remote dependencies of the Empire. The claims of the most distant outposts must be first considered. It is announced in due course that a young cleric, George Augustine Selwyn, who had recently rowed for Cambridge in the famous boat race, has been selected as the pioneer Bishop of New Zealand. In preaching his farewell sermon at Windsor, Selwyn noticed, standing in the crowded aisle, an Eton schoolboy listening as if his very life depended on what he heard. As soon as the service was over, the bishop-designate strode down to greet his youthful auditor. "One of these days," he said, "you must come out and join me!" The boy was John Coleridge Patteson; and 13 years later he eagerly accepted the challenge.

Amid Palm-Fronded Reefs And Blue Lagoons

Joining Selwyn in 1854, he was, in 1861, appointed the first Bishop of Melanesia at the age of 33. To all intents and purposes he had the entire Pacific for his diocese. Fortunately, he possessed an extraordinary faculty for picking up native languages. It seemed as if he had but to listen for a little while to a jargon of a new archipelago, and he was able to make himself intelligible in the unfamiliar tongue. For 15 years he sailed his schooner about these sunlit seas. His system was simplicity itself. Having won the confidence of the people, he induced them to confide to his care one or two of the most intelligent young people on the island. These he carried away to his colleges at Auckland or Norfolk Island; and then, having christianised and educated them, he restored them to their homes to evangelise their peoples.

He disarmed the wildest men by trusting them. His schooner drops anchor off some coral reef in the Pacific. The shore is crowded with excited natives brandishing their spears. Never having seen a white man before, they do not know what to make of the strange apparition. Patteson plunges into the sea, strikes out for the reef, and stands, smiling and defenceless, among them. Or, the ship having been brought to anchor in some blue lagoon, the astonished natives surround it in their canoes. Patteson at once clambers down into one of their craft and places himself at their mercy. In the course of one voyage he landed 70 times amidst crowds of natives naked and armed; yet never once was a hand raised against him. "Savages!" he used to say. "There are no savages! Approach them in the right way; treat them with confidence; assume the existence in them of ordinary human instincts; and you'll find nothing savage about them!" He used to tell stories of amazing courtesies and kindnesses extended to him by ferocious-looking natives.

Surviving Savagery To Be Slain By Treachery

He was, however, slain at last. He was only 44. By this time the slave-trader was at work in the South Seas. One unscrupulous trafficker, admiring the ingenuity of the Bishop's methods, resolved to turn them to his own account. He made his ship look as much like Patteson's as possible and sailed for Nukapu, an island lying between the New Hebrides and the Solomon Islands. He went ashore in a white robe, to impersonate the Bishop, and after some blasphemous buffoonery, invited five young islanders on board. In all innocence, they followed him. They were shown down into the hold where some of the crew were making a pretence of conducting a church service. The hatches were quickly battened down and the ship sailed away with her victims. When the natives ashore realised that their relatives had been treacherously stolen, they swore that they would have blood for blood. They would wreak their vengeance on the Bishop when next he visited them. And they did.

On September 20, 1871, the Bishop himself reached Nukapu. Four canoes came off from the shore. Those on the ship fancied that they sensed something sullen and menacing about the attitude of the natives, but the Bishop, all unsuspecting, sprang into one of the canoes according to his custom. Away they went whilst the crew of the vessel anxiously awaited the Bishop's return. Later, two canoes pushed out from the shore. A couple of women occupied one of them; the other appeared to be empty. When near the ship the women pushed the empty canoe towards it and then paddled swiftly away. It was not empty. In the bottom of it lay something covered with a native mat. Reverent hands lifted the mat, and there, beneath it, lay the body of the Bishop. It bore five ghastly wounds, and, on the breast was a palm branch in which five knots had been tied. Nukapu is merely a palm-covered fleck of sand with blue waves breaking over coral reefs. Among those waving palms there now stands a simple cross with a burnished copper circle—emblems of love divine and life eternal—bearing the inscription that Patteson's life "was here taken by men for whose sake he would willingly have given it." But it needs neither that Pacific monument nor the beautiful memorial pulpit in Exeter Cathedral to keep his memory green.

F W Boreham

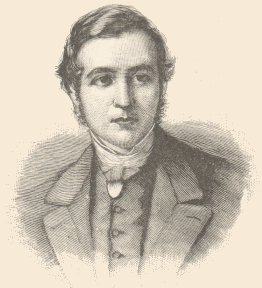

Image: John Coleridge Patteson

<< Home