23 July: Boreham on Coventry Patmore

The Angel in the House

The Angel in the HouseHappily married people all over the world gave a thought yesterday to the anniversary of the birth of a very pure poet. Like Tennyson, Coventry Patmore saw his goal shining clearly from the start. At the age of 15 he consulted a phrenologist who, perhaps with some inkling of the boy's passionate ambition, assured him that he was destined to wear the bays of Virgil. From that moment, even amidst the most depressing conditions, he never once wavered. A streak of Bohemian eccentricity and recklessness in his composition kept him, in his darkest hours, from blank despair. For a time, work as he might, he found it impossible to earn more than a few shillings a week. On one occasion his total wealth amounted to 3/6. His very impecuniosity appealed to his quenchless sense of humour. He entered a restaurant and spent the entire 3/6 at one stroke! Then, proceeding to his rooms, he found a letter containing payment for an article which, written months before, he had almost forgotten. He enjoyed a hearty laugh at the freaks of fortune; and, to the end of the chapter, never again found himself in a situation so dismal.

Indeed, it was about this time that he succeeded in attracting the notice of Browning and of Tennyson. "A very interesting young poet has blushed into bloom this season," wrote Browning to one of his most intimate friends in 1844, the year in which Coventry Patmore came of age. A year later he was introduced to Tennyson, became instantly enamoured of the future laureate, and, to use his own words, followed him about like a dog. A year later, still undaunted by his extreme poverty, he was married to Emily Andrews, and, with his marriage, the work on which his fame must permanently rest was immediately commenced. His happy union with the girl whom he had wooed with romantic devotion, inspired him with an aspiration to compose a monumental poem in praise of wedded love.

An Idyll Marked By Beauty And Brevity

Those who are eager for a more intimate acquaintance with the lady who moved her husband to the most stately epic on womanhood ever written, need not eat out their hearts in futile curiosity. The loveliness of Emily Patmore has not only been chanted in the most exalted strains by her proud and gifted husband; it has been immortalised by the brush of Millais, by the chisel of Woolner, and by the melody of Browning. But, as is natural, none of them can vie with Patmore himself :

The more I praised, the more, she shone,

Her eyes incredulously

bright,

And all her happy beauty blown

Beneath the beams of my

delight.

Unhappily, the felicity that has become so famous was destined to be brief. The transparent delicacy that is so much admired in the painting of Millais was the fatal delicacy of consumption, and, after 15 years of married bliss, in the course of which several children were born, the "Angel in the House" was cruelly snatched from the side of the husband who had so devotedly worshipped her.

But her monument endures. "You have begun an immortal poem," exclaimed Tennyson, when Coventry Patmore read to him some of his opening stanzas, "and if I am no false prophet, it will not be long in winning its way into the hearts of the people." Tennyson's confident prophecy was triumphantly vindicated. The "Angel in the House" was published in 1854, eight years after the poet's happy marriage:—

. . . What

For sweetness like the eight-year's wife

Whose customary love

is not

Her passion, or her play, but

life?

Heaven,

When you into my arms it gave,

Left nought here after to be

given

But grace to

feel the good I have.

The exquisite little volume sold, first in hundreds, and then in thousands, until, before long, a quarter of a million copies had been demanded. And, whilst his dainty masterpiece forged its way to fame, the poet himself was rapidly acquiring a singular and growing ascendancy over the minds of his contemporaries.

A Knight Of The New Chivalry

People like Rossetti, Emerson, Ruskin, Dobell, Worsley, and Aubrey de Vere prized his friendship and luxuriated in his society. In his modesty he considered himself outclassed in such illustrious company. In one of his letters, he confesses to speechless bewilderment that men of outstanding eminence should not only treat him as an equal, but hang upon his lips as though it were in his power to teach them. Austere upon suitable occasions, he was nevertheless an extraordinarily tender hearted and affectionate man. He suffered agonies of remorse if he thought that any criticism of his had been unduly severe. In the literature of the period it is noticeable that those who knew him most intimately are warmest in their assessment of his qualities.

He stands, therefore, as one of the most kingly and authoritative personages of a very notable time; yet it is not on this account that he best deserves to be remembered. Travellers among the high altitudes declare that, in huge masses of glassy ice, they sometimes see, in a perfect state of preservation, the bodies of those who lost their lives among the glaciers many years before. Coventry Patmore has embalmed in a melodious and noble poem the beautiful image of a perfect wife; and as a result, his limpid, chaste and rhythmical verse, delighting the minds of men for centuries to come, will always constitute itself his own most imposing and most enduring monument. In working for the immortality of a very lovely lady, he has, in the process, secured his own.

F W Boreham

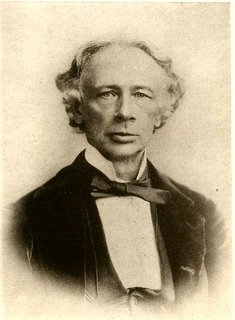

Image: Coventry Patmore

<< Home