15 July: Boreham on Letter Writing

Ladies and Letters

Ladies and LettersFollowing on the introduction of Penny Postage earlier in the year, the world's first postage stamps made their appearance on May 6, 1840.[1] In the course of the generations that have followed, the volume of correspondence has increased by leaps and bounds; but does the advance in quality keep pace with the growth in quantity? Is beauty sacrificed to bulk? Generally speaking there are two kinds of letters—commercial letters and private letters. How far has each affected the other? There can be no shadow of doubt, for example, that the cultivation of business habits by young women has struck a serious blow at the old-fashioned style of intimate correspondence. When, in their thousands, girls entered business colleges, eventually becoming typists and stenographers, it was inevitable that their methods of epistolary self-expression should be vitally influenced by the innovation.

In his amazing autobiography, Anthony Trollope tells how a bundle of his mother's love letters fell into his hands in a singular way, having been found in the house of a stranger who, with fine delicacy and rare courtesy, sent them on to him. This was many years ago, and the letters were then two generations old. Yet Trollope was entranced by the sheer loveliness of their diction. In no novel of Richardson's or Fanny Burneys, he assures us, could we find a correspondence so sweet, so graceful, and so well-expressed. The language in each, though it borders on the romantic, is beautifully chosen and would challenge the analysis of the most severe critic. "What girl of today," Trollope asks, "studies the words with which she shall address her lover or seeks to charm him with the grace of her verbal composition?" Trollope raised this searching question, be it noted, nearly a century ago, when the new day that gave women a place in commerce and public affairs had scarcely dawned.

Influence Of The Old Style On The New

We have travelled a long way since then. The crisp, staccato method of business correspondence has revolutionised all domestic communications. The easy leisureliness of the epistles of our great-grandparents has been swept away in a tornado of rush and bustle. Everything must be sharp and to the point; and, incredible as it must seem, cases have been brought to light in which love letters have been mechanically transcribed with a typewriter! A husband, absent from home on a business trip, does not nowadays write to his wife as, say, Mozart wrote to his in the days of long ago. "Dear little wife," he says, "if only I had a letter from you! If I were to tell you all that I do with your dear likeness, how you would laugh! When I take it out of its case, I say, 'God greet thee, Stanzel! God greet thee, thou rascal, shuttle-cock, pointy-nose, nit-nack, bit and sup!' And when I put it back I let it slip in very slowly, saying, with each little push, 'Now, now, now!' and, at last, quickly, 'Good night, little mouse, sleep well!"' A modern Mozart would find life far too short for this kind of thing. He would send his Stanzel a telegram assuring her of his safe arrival.

There are, it is true, some indications that the pendulum is beginning to swing the other way. There are signs that suggest that, just as the atmosphere of the office has affected the correspondence of the home, so now the atmosphere of the home is commencing to pervade the correspondence of the office. Business men are beginning to recognise, Mr. Thomas Russell declared recently, that the average business letter is far too business-like. It is too cold, too formal, too stereotyped, too trite. It has nothing about it that is persuasive. It is too frigid to be fruitful.

The Variety And Value Of Feminine Influence

It would be a singular irony of circumstance if, after having corrupted the old style of private correspondence by their curt and cold example, the business letter-writer should end up by adopting that old style as his model. It is all to the good if commercial instincts have imparted to domestic communications an aptness, a clarity, and a conciseness of expression that they previously lacked; and it is no less a matter for congratulation if the private letter is infecting business correspondence with a humanness and a sympathetic understanding that appreciably enhance its effectiveness.

The striking thing is that both reformations are attributable to feminine influence. It was the discovery, by the business girls, of the way in which commercial magnates packed a maximum of thought into a minimum of language that led to the abbreviation of the domestic letter; and it is the conviction on the part of prominent business women, that office correspondence is too icy to achieve its purpose, that is introducing into commercial communications a more genial tone. It is interesting to notice that, from time immemorial, women have always played a brave part in connection with such matters, The New Testament, for example, consists, very largely, of a sheaf of letters. Some of the most eminent scholars attribute at least one of them to a woman's hand; whilst, in other of the sacred documents, the feminine element is unmistakable and conspicuous. Nor is this all. For, by common consent, the most important letter in this inspired collection is the epistle to the Romans. But it was one thing, in those days, to write a letter to Rome; it was quite another to secure its conveyance there. And it was a woman who, with superlative courage, undertook to carry it. In days when travel was extremely hazardous, she made her way along the most dangerous roads and across the most perilous seas bearing, as Renan puts it, the entire future of Christian theology under her robe. Of that heroic record, the women of the centuries may very well be proud.

F W Boreham

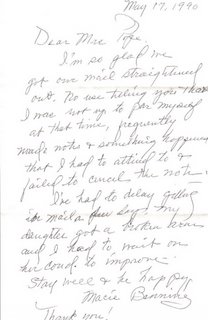

Image: Letters

[1] This editorial appears in the Hobart Mercury on May 6, 1950.

<< Home