17 July: Boreham on Isaac Watts

Father of English Hymnody

On the seventeenth of July 1674 there was born at Southhampton one of the most extraordinary figures that ever adorned English life and English literature. The anniversary of that event is worth commemorating. As Dr. Isaac Watts neared his end, it occurred to the Right Hon. Arthur Onslow, the Speaker of the House of Commons, that he had never made it his business to meet a person with whose high repute everybody was familiar. He therefore resolved, before it was too late, to repair the omission. When the door of Dr Watts' room was thrown open, Mr. Onslow beheld a strange spectacle. For there, not in bed but hunched up in his big study chair, sat a tiny, bony, pinch-faced wisp of humanity, almost hidden in the ample folds of a gaily flowered dressing-gown and looking for all the world like a little wizened Chinese mandarin. As his visitor entered, the shrivelled and dwarfish creature looked up and smiled, not unpleasantly; and, although his voice was a trifle squeaky, the general impression was a distinctly agreeable one. This, if you please, was the poet whose stanzas are destined to be sung always.

To his lifelong chagrin, he was pitifully small. He loathed the sight of his diminutive figure whenever he glimpsed it in a mirror. Nothing stung him more than to hear himself referred to as "little Dr. Watts." He fairly squirmed. It was in self-defence that he sang—

Were I so tall to reach the Pole,

Or grasp the ocean in my

span,

I must be measured by my soul,

The mind's the standard of the man.

The torture of his physical insignificance frayed his nerves. It wove itself into his dreams. And in times of serious sickness his delirium turned the horror topsy-turvy. He raved of his colossal proportions. He was too big to pass through a doorway! He could not squeeze himself into his pulpit! The chairs crumpled like match-wood under him whenever he sat down. His fevered brain had converted the pigmy into a giant!

The Genius That Set Ordinary Speech To Music

And, in some respects, a giant he was. "He stands absolutely alone," says Thomas Wright. "He has no peer; he is the greatest of the great. If nothing from his pen has attained to the popularity of Toplady's 'Rock of Ages,' or is quite so affecting as Cowper's 'God Moves in a Mysterious Way'; if he lacks the mellifluence of Charles Wesley or the equipoise of John Newton, the fact remains that he has written a larger number of hymns of the first rank than any other hymnist."

He was literally a born poet. Even as a small boy there were times when he could not express himself other than in verse. His father—a stern and puritanical soul who had endured several terms of imprisonment for conscience sake—looked askance on this propensity in his boy. But Isaac could not repress it. On one occasion the household was engaged in family worship. A mouse scampered across the floor and ran up the bellrope. Isaac burst into laughter. Prayers over, the father demanded an explanation. Isaac instantly exclaimed—

There was a mouse, for want of stairs,

Ran up a rope to say his prayers.

This was piling crime on crime. The father seized his rod and ordered Isaac to follow him out of the room. The boy threw himself on his knees. "O father," he cried:

O father, father, pity take

And I will no more verses make!

His mother, more sympathetic, once offered a farthing to the boy who should write the best verses. Isaac entered for the prize but attached to his manuscript—

I write not for a farthing, but to try

How I your farthing writers can outvie.

At the age of 21 he accompanied his father to a church service at Southampton. In discussing the experience on the way home, Isaac remarked that he had examined the hymn book and found it extremely disappointing; the hymns were utterly destitute of dignity and beauty. The father, who had by this time come to realise that his son's poetic impulses were incapable of restraint, advised him to write something better himself. And, that very afternoon, Isaac set to work.

A Singer Whose Voice Steadily Grows In Volume

No hymns have been more universal or more persistent in their appeal than those of Dr. Watts; they have been translated into countless languages. Novelists are generally supposed to portray the deeper instincts and impulses of human life, and, that being so, it is significant that men like Arnold Bennett and women like L. T. Meade have woven great works of fiction around one of Isaac Watts' best known hymns. Nor can we forget that Matthew Arnold, an hour or two before he so suddenly died, joined with a congregation at Liverpool in singing Dr. Watts' "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross." A servant heard him crooning the words to himself as he went down to dinner. "Ah, yes," he remarked at table, "the Cross still stands, and, in the straits of the soul, makes its ancient appeal!" He hurried out to catch a tram, collapsed of heart failure, and was gone!

Isaac Watts was a choice spirit. Blaming his petite stature for his rejection at the hands of the beautiful blue-eyed and auburn-haired Elizabeth Singer, he remained a bachelor to the end. The finest testimony to the sweetness and charm of his disposition is found in the fact that, in 1714, he went to spend a week with Sir Thomas and Lady Abney. The visit extended until he died in 1748, and Lady Abney said that he became more honoured and beloved of the household with every day that passed. A monument marks his resting-place at Bunhill Fields; another is to be found in Westminster Abbey. Other statues stand at Southampton and elsewhere. But his most fitting memorial is the stained-glass window at Freeby in Leicestershire which represents him as still surveying the Cross—that wondrous Cross on which the Prince of Glory died—around which all his minstrelsy had moved.

F W Boreham

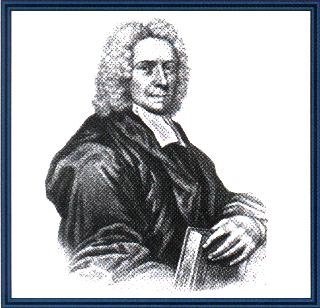

Image: Isaac Watts

<< Home