31 July: Boreham on William Knibb

The Champion of the Slaves

The Champion of the SlavesThe thirty-first of July was far and away the greatest day in the colourful life of William Knibb. It is by no means certain that Knibb has ever been given his just place in the brave records of the emancipation movement. He was born in those momentous days in which Lord Nelson was passing from one magnificent victory to another, and in which the dread of a Napoleonic invasion hung like a dark cloud over the Homeland, and the abject condition of the coloured slaves of the West Indies nearly broke his heart. Jamaica was usually described in those days as the loveliest land on the face of the earth. But to Knibb it appeared, not as Paradise, but as Paradise Lost. Everything impressed him, when he landed, as being revolting, hideous, abominable. The plains were fruitful, it is true, and the valleys wonderfully fair, and yet, from the whole island, there seemed to rise, not a song of gladness, but a cry of anguish. For Jamaica was pre-eminently the abode of slavery.

The people were not their own; and they knew it. Masters might be kind or cruel; it made little difference. Life was destitute of security. Among the ebony-skinned, thick-lipped, woolly-haired creatures who swarmed around Knibb on his arrival in 1825, there was no such thing as marriage: any unions that the coloured people contracted among themselves were subject to the exigencies of future sales. Children with laughing eyes and pearly teeth were scampering about everywhere: but they had all been bred for the market and would be auctioned as soon as their limbs were set. Stalwart youths saw their dusky sweethearts grow in shapeliness and charm; but trembled lest their comeliness should catch the eye of the overseer or the owner. Dreading the worst, they hoped for the best; and the best for which they could hope was that they and their chosen partners might be permitted to live together for a few years in some little hut among the bushes, producing children for the monthly sales. And if any slave dared to lift a hand or raise a voice in protest, they were but inviting the horrors of the treadmill and the lash. The only thing that stood between the slave and unbridled cruelty was their market value.

One Brother Takes The Other's Place

Jamaica found no place on William Knibb's original programme. He and his elder brother, Thomas, were apprenticed to a printer at Bristol. Thomas set his heart on being a missionary, but William resolved to follow a commercial career to the end of the chapter. In due course Thomas realised his aspiration; was trained as a missionary; was designated to Jamaica; arrived there in January, 1823, and died of malaria three months later. The news profoundly affected William. It seemed to him not only a calamity but a challenge. He recalled the talks in which Thomas had outlined his dreams. William could not bear to think that death had cheated the world of such superb gains. He resolved to take his dead brother's place. He would evangelise the oppressed people for whom Thomas had surrendered his life, and, perhaps, break their chains. The change was all to the good. Thomas could never have done the work that William did. Thomas was frail and shrinking, William was lion-like and determined. He was, as somebody said, made to mount the whirlwind and to ride the storm. Thomas was a grassy knoll: William was a volcano in eruption.

As soon as he arrived in Jamaica, he resolved that, at any cost, slavery must go; and the cost was heartbreaking. His work involved him in the most excruciating sacrifices. In that fever-laden climate he buried his children almost as soon as they were born. He was persecuted; charged with rebellion; dragged about the island, and subjected to every conceivable indignity. He was spared no humiliation that could tend to his embarrassment and discomfiture. He visited England, stirring the country with righteous indignation. The entire nation was moved by the passion and the pathos of those tremendous appeals. And at last, he won.

A Short Life But A Triumphant One

Few scenes in history are more dramatic than the scene witnessed in Jamaica on the night of July 31, 1838, the night on which the emancipation of the slaves came into force. The slaves dug a grave. Preparing a most exquisitely carved and polished coffin, they flung into it a slave chain, a slave whip, a slave hat—all the insignia of their degradation. "The monster is dying!" cried William Knibb as the hour approached; as the clock struck, he shouted: "The monster is dead!" The coffin was lowered into the yawning grave whilst the immense concourse of excited coloured people sang exultantly:

Now, Slavery, we lay thy vile form in the dust,

And, buried for ever; there

let it remain,

And, rotted and covered with infamy's rust,

Be every

man's whip and his fetter and chain.

The land rang with doxologies. The

beautiful island had been delivered from its hideous curse. The chains were

shattered: the slaves were free.

Surrounded by the people to whom he had been so passionately attached and for whom he had given unstintingly the full measure of his devotion, Knibb died a few years later at the age of 42. On his death bed he was able to reflect with gratification on the circumstance that, he had not only secured the emancipation of the West Indian slaves, but had inspired a hatred of slavery in the hearts of all the people of the world. The fact that he had moved the British Government to introduce an act voting £20,000,000 to meet the cost of the liberation of those for whom he pleaded, is evidence in itself of the influence that he wielded. He died, conscious of having followed the gleam in scorn of consequence: he knew that he had earned the devoted gratitude of the people whose fetters he had broken: and he was happy in having brought to completion the work that he had accepted from his dead brother's hands.

F W Boreham

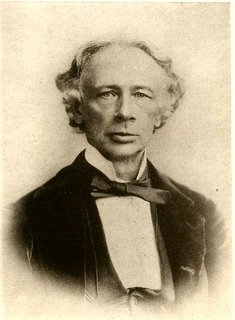

Image: William Knibb

The Centenary of William Wilberforce

The Centenary of William Wilberforce A Master Maestro

A Master Maestro

A Domestic Triumph

A Domestic Triumph

A Maker of Men

A Maker of Men

The Romance of a Poem

The Romance of a Poem