21 December: Boreham on Benjamin Disraeli

On the Side of the Angels

On the Side of the AngelsIt was on December 21, 1804, that Benjamin Disraeli was born. He was easily the most impenetrable personality of his day. Nobody knew what to make of him. He was, as T. P. O'Connor put it, a sphinx, a mummy, an inscrutable enigma. He bewildered his friends, baffled his enemies and was the despair of all those who attempted to assess his motives, fathom his character, or analyse his complex and elusive personality.

There were times when his most ardent admirers suspected that he was an unconscionable humbug. There were times when his most relentless foes realised that he was capable of splendid chivalry, lofty heroism, and purest devotion. He stands as the mystery man of British politics. He loved mystery; he courted mystery; he deliberately enshrouded himself in a golden haze of impenetrable mystery, and something of that obscuring veil will always cling to his memory.

When he first appeared in Parliament, everybody stared incredulously. Nothing of the kind had been seen at Westminster. There was, we are assured by those who saw him at that time, something irresistibly comic about the amazing spectacle. He appeared in a fantastic and coxcombical costume that he wore with obvious self-consciousness—velvet coat thrown wide open, ruffles on the sleeves, an elaborate embroidered waistcoat from which issued voluminous folds of frill, shoes adorned with red rosettes, black hair pomaded and elaborately curled, his whole person redolent of the perfumes of Araby.

The theatrical young dandy seemed to have burst upon men from some other world. He exhaled an atmosphere totally foreign to that of the classic halls that he had irreverently invaded. His face, his figure, his gait, his dress, his style of speech were all alike sensational. This youthful upstart was out to kill.

A Subtle Strategy In Statecraft

But there was method in his madness. Disraeli knew that he had it in him to say things that would sting and stab and startle. He shrewdly realised that those things would strike their hearers with the greater force coming from one whom they had learned to regard as a brainless dandy. His affectation was itself an affectation.

Froude avers that it is impossible to convey to readers the overwhelming effect of sudden flashes of electrifying eloquence emanating from so unpromising a source. He would rise amid titters of derision and send his hearers to their homes enchanted. It was by such strange arts that he won his initial fame. He practised them, less ostentatiously but more skilfully, to the end of his days.

Froude closes his monumental "Life of Beaconsfield" in a minor key. He sorrowfully admits that, vast as was his hero's authority, and dazzling as were his powers, it is nevertheless a lamentable but indisputable fact that, in the truest sense, he was not great. In estimating greatness, whether in art, science, religion, or public life, Froude lays it down as an axiom that there must be one indispensable ingredient—the man must forget himself in his work.

If any fraction of his attention is given to the honours and rewards which success will bring him, there will be a corresponding taint of weakness in what he does. He cannot produce a great poem, he cannot paint a great picture, he cannot discover the most subtle secrets of science, because all these achievements require a whole, and not a divided, mind. A man whose object is to gain something for himself often attains it, but, when his personal life is over, his work and his reputation perish with him.

Possessed A Flair For Friends

Judged by this standard, Froude is compelled to deny real greatness to Beaconsfield. He always had some selfish or party end in view. His motives were never transparent. His eye was never single. His most enthusiastic admirers admit that his finest efforts were marred by a haunting uncertainty as to his real sincerity. He was a superb actor; and the worst of being a clever actor is that nobody knows whether you are pleading or merely performing.

Disraeli was in ceaseless trouble at this point. Yet the fact remains that he displayed qualities and developed powers that have earned for him our abiding gratitude. He was an intense patriot. He loved his country with a passionate and ever-deepening devotion. Lord George Hamilton declares that he was the soul of honour, the staunchest, truest friend that any man could possibly possess. And, as he himself proclaimed, in the course of the greatest scientific controversy of the nineteenth century, he was always on the side of the angels.

At the close of his "Life of Beaconsfield," Sir Edward Clarke depicts four eminent friends of Disraeli standing beside his grave, speaking of him in terms of sincerest admiration and affection. "Then," adds Sir Edward, "I seemed to hear the sorrowing voice of a Queen in a distant palace. Her Majesty unhesitatingly declared, in a voice vibrant with genuine emotion, that Lord Beaconsfield was the most considerate, the most devoted, as well as one of the wisest Ministers she ever had.

"And," continues Sir Edward Clarke, "as I turned away from the primrose covered grave, I thought I heard a whisper from the adjoining tomb 'God bless you, my kindest and dearest,' a spectral voice seemed to say, 'you were to me a perfect husband!'" Sir Edward is forced to the conclusion that there must have been some quality of greatness in a man of whom such things could be truly and feelingly said. Nobody is likely to deny it; and Froude himself, notwithstanding all that he has written in the biography, would probably add his concurrence.

F W Boreham

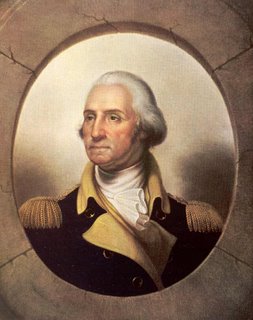

Image: Benjamin Disraeli

The Cook

The Cook Splendour and Squalor

Splendour and Squalor

The Literature of Escape

The Literature of Escape

A Titan of the West

A Titan of the West What Might Have Been

What Might Have Been The Glory of an Island

The Glory of an Island

King of the Kailyard

King of the Kailyard The Apostle of Mutual Aid

The Apostle of Mutual Aid