14 December: Boreham on George Washington

A Titan of the West

A Titan of the WestThe people of the United States will set today aside as the anniversary of the death of George Washington. However, it was on Feb. 22, 1732, that, in an obscure farm on the green banks of the Potomac, the founder of American destiny first appeared. Washington stands as a majestic cosmopolite. He is one of earth's magnificent originals. He was the architect of a new order. In the famous city that bears his name, the most impressive spectacle is the Pool of Reflection. At one end of this mirror-like lake stands the tall and tapering obelisk that symbolises the mighty simplicity and inflexible uprightness of Washington; at the other end stands the stately temple erected to the heroic memory of Lincoln. As visitors stroll along the banks of this idyllic pool, admiring the two noble monuments duplicated by their perfect reflections in the limpid waters, it is usual to institute a comparison between the two Presidents and to speculate as to which of the twain was really the greater.

It is difficult to say. The massive personality of Lincoln overawes the imagination. Too gigantic to be localised, he bursts all the bounds of nationality and takes his place in history as a citizen of all nations and of all ages. With the fine stroke and gesture of a king, he piloted the civilisation of the West through the most momentous crisis of its history, and, in doing so, he established principles that will stand as the landmarks of statescraft as long as the world endures.

Learning Statesmanship In School Of Solitude

Lincoln has won all our hearts by his gallant struggle with early hardships and cruel privations. But was Washington's fight less grim? In his case, there may not have been the same element of poverty. In temper and breeding he was essentially an aristocrat. Yet the Spartan qualities were not lacking. His lot, almost from infancy, was the lot of an orphan. His father died when he was only eleven, and from his earliest days he was compelled to rough it. "No academy welcomed him to its shades," as Bancroft puts it; "no college crowned him with its honours; to read, to write, to cipher—these were his highest degrees in knowledge." He developed, however, an uncanny faculty for measuring land, and, at the age of sixteen, boldly proclaimed himself a surveyor. And he made that proud announcement in the assured conviction that he had mastered the essential principles of his profession and would be able to render honest service to those who conferred their patronage upon him.

But it was a desperate business. In his famous history, Sir George Otto Trevelyan says that, at an age when a youth of his rank in England would have been shirking a lecture in order to visit the racecourse, George Washington was surveying the gloomy valleys of the Alleghany Mountains and the remotest banks of the Shenandoah waters. He spent most of his days among naked savages who glanced enviously at his scalp, and among uncouth emigrants who could speak no word of English. His nights were spent in the open; he seldom slept in a bed; held a bearskin to be a luxurious couch and was thankful to be permitted to throw himself down at dark on a little hay or straw. Much more often he rested under the shelter of a tree, to be disturbed during the night by the prowl of a wild beast or the slither of a rattlesnake. For three years he dwelt in these vast solitudes, catching and cooking his own food, and the experience that he gained in the trackless and lonely forests proved invaluable to him when, in later years, he found himself at the head of the American armies. He led his forces into the leafy wilderness with the confidence of one who knew every hollow and fastness; and, as a consequence, he performed such miracles of military leadership as won for him the astonished admiration of the world.

Brilliant Powers Eclipsed By Sterling Character

The fact is that Washington carved a path to glory by his remarkable facility for combining qualities seldom found in conjunction. He was, for example, as great in council as in war, as distinguished in statecraft as in soldiership. In the usual acceptation of the term, he was not an orator. His maiden speech was a single lame and broken sentence, stammered out in acknowledgment of a resolution thanking him for his military services. At the height of his career, his speeches seldom exceeded ten minutes; but every word was to the point; and, when he resumed his seat, the course of the assembly was invariably clear. Yet on none of these qualities, in themselves, was his fame founded.

His real glory lay in his personal character. His supreme claim on our gratitude rests upon the circumstance that he gave us a concrete and classical example of a man possessed of remarkable attractiveness and commanding powers, yet animated, at the same time, by the purest, most patriotic and most unselfish motives. Macaulay only once refers to him, and in that solitary allusion he dismisses him with half a dozen words; yet those meagre syllables enshrine a tribute which could not in many volumes be excelled. For, in summing up his elegant and masterly eulogy of Hampden, the historian says that in the days that followed the Civil War, "England missed the sobriety, the self-command, the perfect soundness of judgment, the perfect rectitude of intention to which the history of revolutions furnishes no parallel, or furnishes a parallel in Washington alone." When, at the end of his campaign, Washington took farewell of his officers, the official record declares that every man was in tears, and that many of those present, ordinarily strangers to such softness, kissed his hand, or even his face, as he passed in silence from the room. It was a touching tribute to that personal charm which, joined with the most dazzling brilliance, had made him the hero of the nation and the idol of each separate individual who had felt the irresistible spell of his magnetic personality.

F W Boreham

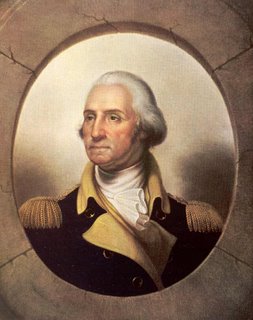

Image: George Washington

<< Home