6 December: Boreham on Governor Bligh

A Study in Light and Shade

A Study in Light and ShadeAn interesting study is presented for our contemplation by the circumstance, that we mark today the anniversary of the death of Governor Bligh. Incidentally, the fact may remind us that, in one respect, the infancy of Australia is unique. No other nation under heaven can show, in the crude records of its early days, such a galaxy of massive, gnarled, dynamic personalities. They seem to match the giant gums of our virgin bush. There is something tremendous, even terrifying, about the war-scarred and weatherbeaten stalwarts by whose sinewy hands the malleable destinies of these southern lands were hammered into shape.

Governor Bligh is a case in point. Some of the most eminent writers of all time, including Lord Byron and George Borrow, have undertaken to elucidate for us the mystery of Bligh's enigmatic individuality, but have left us in a welter of hopeless confusion.

Bligh was a faggot of contradictions, an inextricable tangle of inharmonious and hostile qualities. He could be as suave as a courtier, as shrewd as a plenipotentiary, as brave as a lion, and as ferocious as a tiger. He could produce a smile that, conferred upon a subordinate, would make the young officer feel as if he had been invested with a knighthood; and he could unleash a temper that would send a shudder through a battleship or rock Government House to its very foundations.

A Storm Centre By Sea And Shore

Bligh earned his fame the hard way. As to his boyhood, we know nothing and as to his birthplace, we know less. Pints of ink have heen squandered in attempts to prove that he was born in this pretty little Cornish village or in that one.

But what does it matter? The things that do matter are that, at the age of eight, he entered the Navy as a kind of fag to Capt. Keith Stewart, of H.M.S. Monmouth; that, at 16, he became an able seaman on H.M.S. Hunter; that six years later, he was chosen by Capt. Cook to be master of the Resolution on the voyage that cost the redoubtable navigator his life; and that, following his never-to-be-forgotten adventure on the Bounty, he served with distinction under Nelson in the Battle of Copenhagen. "With all my heart I thank you, Bligh," wrote Nelson, concerning that engagement. "You have supported me nobly." By this time Bligh was 47.

In the turbulent hurricane of his stormy life, the gale twice reached peak proportions. The first was when, on April 28, 1789, the mutineers of the Bounty turned him adrift, with 18 companions, in an open boat. The second was when, on January 26, 1808—the 20th anniversary of the foundation of Australia—he was seized by his enemies at Government House, Sydney, and placed under arrest. Four hundred troops marched from their barracks to the tune of "The British Grenadiers" and, swarming into Government House, soon made the Governor their prisoner.

The first of these dramatic episodes led to one of the most amazing epics of the sea ever recorded. As Dr. Mockaness points out, in his monumental biography of Bligh, it is a feat that takes one's breath away. To cross nearly 4,000 miles in a small boat, across uncharted seas, in tempestuous weather, subject to attacks by savages, with totally inadequate provisions, and with companions of whose loyalty he had every reason to be suspicious; all this represents on exploit of almost incredible splendour.

A Scholar Of A Noble School

The debacle at Government House is another story; but, in the judgment of Dr. Mackaness, Bligh again emerges with flying colours. From an enormous mass of material, Dr. Mackaness has compiled "The Case for the Rebels" and "The Case for the Governor;" and, whilst he leaves his readers at liberty to reach their own conclusions, he does not attempt to conceal his own admiration for the behaviour of Bligh.

Bligh was a member of the Banks Brigade. Not content with having financed the expeditions of Captain Cook and with having served on those famous voyages as naturalist, Sir Joseph Banks devoted the days of his retirement to ceaseless efforts to inspire younger men with a passion for exploration. Among other triumphs, he contrived to fire the fancy of Mungo Park, who pioneered the opening up of Africa; of Lachlan Macquarie, who undertook to inaugurate an era of pathfinding in Australia; and of John Franklin, who forced a way through the North-West Passage.

It was under the auspices of Sir Joseph Banks that Bligh was appointed to New South Wales. The fact that, after his return to London, Bligh was promoted to be vice-admiral indicates the official attitude towards the hot-head who had given Whitehall so many headaches. Dr. Mackaness closes his biography by declaring that as an illustrious navigator, bred in the school of Captain Cook, Bligh stands side by side with Vancouver, Flinders, and King; whilst, for audacity and skill, his name will always be bracketed with those of Phillip, Macquarie, and Bourke as men who never turned their backs but marched breast forward.

F W Boreham

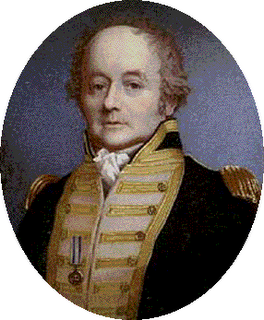

Image: Governor Bligh

<< Home