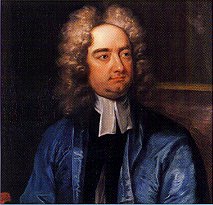

30 November: Boreham on Jonathan Swift

A Cynic and his Secret

A Cynic and his SecretIt is difficult to mention the name of Jonathan Swift, whose birthday this is, without being oppressed by his sheer tremendousness. To think of him, as Thackeray once said, is like thinking of an empire falling. He was massive, portentous, ghoulish. As darksome as a noonday thundercloud, he was at the same time as brilliant as forked lightning at midnight. There are times when he excites not only our applause but our affection. We sit at his feet fascinated and entranced. The sprightliness of his wit and the resistlessness of his mirth captivate our fancy and hold us spellbound. Then, quite suddenly and without any apparent reason, the fine face becomes disfigured by a sneer. He becomes cynical, sardonic, caustic, brutal, and displays ungovernable passion. He shocks us by his coarseness, and we turn away in disillusionment and disgust. There was one woman whose scrutiny detected under the forbidding exterior of Swift's appalling personality potential virtues that no eyes but hers could see. And, in point of fact, those latent potentialities were almost transformed into concrete actualities under the spell of her presence, her trust and her charm. Mr. Austin Dobson says that when, in writing to Stella, Swift bent over the paper that her dainty fingers were so soon to handle and her fond eyes to scan, the leer and the grimace entirely vanished from his countenance, and his expression became indescribably wistful and tender.

Singularly Lovable

The whole man was transfigured. In the process of loving, he himself became singularly lovable. The relationship between these two is one of the most mystifying in our annals. They were both orphans, and both fell under the patronage and protection of Sir William Temple at Moor Park. She was some years his junior, and, in the early days of their acquaintance, he was engaged as her tutor. "She grew," he tells us, "into a most charming girl and was looked upon as one of the most beautiful, most graceful, and most agreeable young women in London. Her hair was blacker than a raven and every feature in her face was perfection." If only Stella had been given a free hand with this gnarled lover of hers what a masterpiece she might have produced!

Swift's correspondence with Stella presents us with some of the most exquisite love letters ever written. It is scarcely credible that they issued from the same pen as the pages that awaken our horror and our indignation. Under Mr. Dobson's guidance we have seen his rugged face assume an unwanted sweetness as he indites his letters to her. It is worthwhile glancing again at the moment at which a letter from her is brought to him. Lying in bed, he hesitates to open it, so that he can the longer enjoy, the bliss of anticipation. Since he cannot caress her shapely hand, he fondly strokes the envelope. "And now," he exclaims, "let us see what this saucy, dear, dear letter says! Come out, letter; come out of the envelope! I see it there, but it will not come out. Come out again, I say! Ah, here it is! Now hold up your head like a good letter!" And so on. There is no end to his softness and sentimentality when Stella is concerned. She lit in his soul a lofty arid ardent devotion. He cannot bear her to be out of his sight. On one occasion they were separated for 10 days. He prays, he tells her, that he may never again know such anguish as long as he lives. Her death, when he was 61, nearly killed him. No man ever loved a woman more purely than he loved her. She was the light of his eyes and the breath of his nostrils. His sun rose when she appeared and set when she withdrew. He watched her raven hair as, with the years, it became as white as snow. He lavished on her all the treasure of a singularly wayward and passionate heart. Did they ever marry? Nobody knows. He who carefully studies the arguments on both sides will find them equally unconvincing. If they did marry, the marriage consisted purely of a ceremony—a solemn and legal assurance he desired to give her that no other woman should ever be his wife. Three reasons have been advanced to explain Swift's amazing self-denial. To begin with, Stella was of doubtful origin and Swift was haunted by an ugly suspicion that, possibly, she was his own half-sister. Quite apart from this, however, he felt strongly that no man afflicted with an incurable disease ought to marry. Swift suffered ceaseless torture from such a malady, and he shrank from the idea of bequeathing his agonies to another generation.

Approach Of Insanity

And then there stands the stark and undeniable fact that Swift knew perfectly well that, in all human probability, his body would survive his brain. His whole life was clouded by the steady approach of insanity. His devotion to Stella recoiled from the thought of involving her in so terrible a calamity. And so, with a touchingly unselfish fidelity, he loved her to the day of her death. And, having laid her to rest, he plunged into the abysmal darkness that he had so long dreaded. His brilliant mind became a total wreck. After his death a mellow envelope was found among his papers. It contained a single lock cut from Stella's head. On the envelope he had scrawled: "Only a woman's hair." It was the last pathetic episode in a strangely captivating and uplifting romance. What would Swift have been if Stella had taken the place to which, in normal circumstances, she would have ascended? Some of the most eminent critics—men like William Hazlitt, Sir Leslie Stephen, and Lord Macaulay—have attempted to analyse the baffling personality of Jonathan Swift, but in every case they have abandoned the task in despair. He stands before us a majestic, melancholy, depressing figure, albeit marked by a certain terrific grandeur. We owe him much. After burning the rubbish that is fit only for the incinerator, we still possess "Gulliver's Travels," and by Gulliver the world will always prefer to remember him. Yet even Gulliver was written spitefully. The grotesque characters in Lilliput and Brobdingnag were created to symbolise certain eminent personages of that drab and uninteresting period; the diverting incidents were designed as caricatures and lampoons of current happenings. Upon the Twentieth Century, that political significance is entirely lost. As to the persons pilloried and the actions ridiculed nobody now knows and nobody now cares. Yet strangely enough, the story, stripped of its original design, still stands among our classics. The bitterness is spent; the venom ceases to sting; the acid has so mellowed as to have become appetising. The humour alone remains and, with it, the memory of a colossal personality who stands among the magnificent might-have-beens of history.

F W Boreham

Image: Jonathan Swift

<< Home