14 June: Boreham on Reading

A Lost Delight

A Lost DelightAt midwinter, our grandfathers and grandmothers assembled the household round the glowing fire, and, whilst the womenfolk knitted and did fancy-work, the head of the family would take a book and, to the delight of everybody in the circle, would read aloud.[1] But progress has its price. When journalism became popular, oratory suffered. Political leaders no longer attempted to sway their immediate listeners by masterpieces of rhetoric, but, turning their attention to the Press gallery, they uttered skilfully framed statements that would read well in the next day's newspapers. Similarly, the multiplication of cheap literature played havoc with the old fashioned art of sustained conversation. In his "Life of Sir George Burns," Edwin Hodder says that, whilst the eighteenth century was a century of great talkers, the nineteenth was a century of great readers. Is it possible that, in our own time, the radio, with its dramatic, musical and elocutionary entertainment, has superseded the pleasant old practice of reading aloud?

In the early days of English literature the habit was common for two reasons. Books were expensive and illiteracy was common. Great numbers of those who desired to devour the contents of a volume were unable either to purchase or to read it. The inevitable consequence was that men clubbed together for the purchase of a book and arranged for some educated person to read it to them. Sir John Herschel has told us how, at Slough, 200 years ago, the local blacksmith gathered the villagers round the fire of his forge of an evening and, perched on the anvil, read Richardson's "Pamela" aloud to them; and, when they were assured of the triumph and marriage of the virtuous heroine, they were so transported with delight that they rushed pellmell from the smithy to the church and set the belfry pealing. Even when, a century later, the works of Charles Dickens appeared—at first in monthly parts—groups of people gathered in taverns, drawing rooms kitchens, and barns to hear the latest instalment of "Bleak House" or "Oliver Twist" read aloud to them.

The Forging Of A Friendly Bond

Reading aloud has a cementing and unifying value. Those who have laughed together over the quips and drolleries of Sam Weller, and who have felt their eyes moisten as they listened together to the story of the death of Little Nell, find themselves united henceforth by common interests, and every casual reference to any episode in the romance will constitute itself an effective link between them. Nor is this all; there are subsidiary advantages. Reading aloud is good from a physiological point of view; it encourages deep breathing. It is good from an elocutionary point of view; the modulation of the voice and the natural expression of all kinds of emotions become habitual, almost mechanical. It is good from a literary point of view; it is wonderful how many books are read, and read thoroughly, for in reading aloud there is no skimming. And it is good from an educational point of view; the mind picks up new words and new ideas much more readily on hearing them or uttering them than it does on simply seeing those phrases or thoughts in cold type.

American writers are never tired of telling of the profound influence which, in the early days of Western history, this modest practice wielded. In "The Light in the Clearing"—a book which the author asks us to regard as history rather than as fiction—Irving Bacheller makes his hero bear witness to the way in which his entire career was affected by the custom of reading aloud. "The Candles were lighted in the cabin," he says, "and novelist, statesman, explorer, poet, and preacher came from the ends of the earth to pour their souls into ours. How the reading bound us to the home! Nobody wanted to go out. While Aunt Deel read, our hands were busy making lighters or splint brooms or paring or quartering or stringing the apples, or perhaps in cracking butternuts. That reading by candlelight awoke my interest in east and west and north and south and in the skies above them."

The Charms Of Frugality And Sublimity

Not the least among the attractions of the oldtime habit is its sheer inexpensiveness. The high cost of living notwithstanding, it is still possible for those of frugal mind to obtain a maximum of enjoyment for a minimum of outlay. In his journal, old John Dillman tells how, sauntering down the Strand one evening, he bought for a shilling a second-hand but well-bound copy of "Pickwick Papers." Bearing it proudly home, he read it aloud to his wife and children. Night after night, as soon as the tea things were washed up and put away, they all drew their chairs to the fire and John read a couple of chapters of Mr. Pickwick's adventures. "How we laughed and cried together!" he says. "It may be that, in the course of our lives, we have spent still happier evenings; but, if so, I cannot recall them. The book lasted us over a month." Here are eight people spending thirty or more profitable evenings in return for the expenditure of a single shilling!

In one of his most affecting poems, Bret Harte has borne witness to the softening and uplifting influence exerted on the roughest miners of the Wild West by the reading aloud round the campfires of the noblest English romances. And, pursuing this attractive line of research a little further, we come upon such scenes as Burns describes in his "Cottar's Saturday Night," the scenes from which, he says, "old Scotia's grandeur springs."

The priest-like father reads the sacred page,

How Abram was the friend of God on high;

Or Moses bade eternal warfare wage

With Amalek's ungracious progeny;

Or how the royal bard did groaning lie

Beneath the stroke of heaven's avenging ire;

Or Job's pathetic plaint and wailing cry;

Or rapt Isaiah's wild, seraphic fire;

Or other sacred seers that tune the sacred lyre.

Beyond the shadow of a doubt, the time honoured custom of reading aloud, whether on this exalted plane or on the ordinary levels of comedy and romance, has proved in times past an incalculable enrichment of domestic and national life; and, even in these days of greater pressure and multiplying counter attractions, it would be all to the good if the ancient practice could be, to some extent, recaptured.

F W Boreham

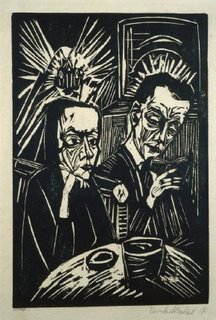

Image: Raeding Aloud

[1] This editorial appears in the Hobart Mercury on February 5, 1949.

<< Home