9 June: Boreham on Charles Dickens

The Veracity of Fiction

The Veracity of FictionIt was a great moment in the romance of this little world when, in the dusk of a Winter's evening in 1833, a lanky youth in a very antiquated top hat and a very rusty frock coat, dropped a carefully inscribed manuscript in a dark letterbox in a dark office up a dark court in Fleet Street. Charles Dickens, the anniversary of whose death we mark today, has told the story of that initial venture, and he describes the agitation that he experienced when he read that first sketch, "Mr. Minns and His Cousin," in all the bravery of print. Having purchased the magazine at a stall in the Strand, he walked, scarcely knowing whither, down past Trafalgar Square, along Whitehall, to the Houses of Parliament. "I turned into Westminster Hall for half an hour," he says, "because my eyes were so dimmed with joy and pride that they could not bear the street and were not fit to be seen there." That was the beginning of the most amazing literary career in human history.

The really notable thing about Dickens is the fact that he established so stupendous a business on so extremely modest a capital. He brought to his task no external advantages whatever. His childhood was spent in absolute poverty and his education was of the scantiest. But he was under no illusion about either his powers or his limitations. He knew what he knew, and he knew of what he was ignorant. He was too wise to attempt work that was beyond his talents. He possessed an unrivalled knowledge of English life and a perfect command of the English language. With this stock-in-trade he felt that something might be done, and, as all the world knows, he did it.

Fact Revealed Through Diaphanous Fancy

Dickens bought his knowledge of the world at a cruel price. His boyhood was a sordid and terrible affair. In a paper found after his death, he says that he could never bring himself to repeat, even to his wife, the horrors that he endured in those early days. His memories of the menial and disgusting tasks assigned him in a blacking factory were such that, to the last day of his life, the smell of blacking induced instant nausea. From this extreme of wretchedness and degradation, he passed later into the best society of the nineteenth century. Knowing life at both ends, he knew also every intervening phase. He saw humanity in every garb and from every conceivable angle. The panorama fascinated his hungry mind. Each detail fastened itself upon his memory, and, thrown into the melting pot of his vigorous mentality, assumed a new and striking form under the witchery of his vivid imagination.

In the delineation of his characters and in the development of his plots, Dickens is sometimes a caricaturist, but he is always something more. He is always the man of scintillating genius, penetrating insight, and broad human sympathies; he is always rendering articulate the heart throbs of the people; he is, in short, an artist in real life. Alike in his pathos and in his humour, his pages carry conviction; they ring with reality. As Dr. Compton Rickett says in his "History of English Literature," Dickens is the great storyteller of the common lives of the common people. "He is great because, though dealing continually with little worries, little hardships, and little pleasures, he made the dullest of lives in the drabbest of streets as enchanting as a fairy tale." He wove his wondrous web out of the stuff that dreams are made of; yet it was compounded of the very essence of flesh-and-blood actuality.

Reality Awakens Immediate Response

It is the unique achievement of Dickens that he has made his creations so familiar that they may safely be introduced in their own right. If a speaker refers to a character in one of the novels of Thackeray or Scott or George Eliot, they feel themself under an obligation to mention the book, or at least the author's name. But any man may refer to Jingle or Quilp or Squeers or Sam Weller or Bill Sikes or Betsy Prig without feeling under the slightest necessity to amplify the allusion. Indeed, the average audience would feel that the speaker was affronting its intelligence if, after such a reference, he laboriously explained that the citation was from Dickens. The characters stand on their own feet. We should immediately recognise Mr. Micawber or Paul Dombey or Uriah Heep or Bob Cratchit if we had the rare good fortune to meet one of them on the street. Or, to bring the supposition within the stricter limits of possibility, if one of the guests at a fancy-dress ball was to masquerade as Mr. Pecksniff, Jerry Cruncher, Mrs. Bardell, Smike, Oliver Twist, or Little Nell, he or she would be as easily identified by everybody in the room as if the guest had assumed the role of an eminent historical personage.

Life answers to life, as, in another connotation, love answers to love. For this reason, the work of Dickens met with immediate response and recognition. It took men a few generations to discover fully the genius of Shakespeare and of Milton; but, as soon as Dickens began to pipe, the crowd began to dance. Although he passed away at the comparatively early age of 58, he had made a fortune and earned a fame such as none of his literary predecessors had ever enjoyed. And when, on that soft June day in 1870, he died, a belt of genuine and profound grief girdled the entire world. It stands to his everlasting credit that he never once struck a really false note. Ruskin used to say that the amazing thing about Dickens was neither his pathos, which has never been surpassed, nor his humour, which was peculiarly his own, but his unswerving fidelity to truth. "The things that he tells us," Ruskin declares, "are always true. He is entirely right in the main purpose and drift of every book that he wrote. If you examine all the evidence, you will find that his view is the finally right one, grossly and sharply told." Thus Dickens stands as the representative, not only of English literature, but of English life; and since, to him, life was wonderfully sweet, he moved the hearts of all who enjoy life and find it good.

F W Boreham

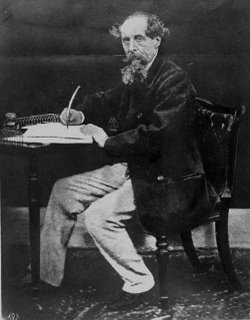

Image: Charles Dickens

<< Home