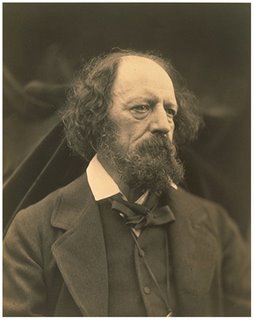

6 October: Boreham on Alfred Tennyson

A Singer's Coronation

A Singer's CoronationOn this, the anniversary of his death, it is interesting to reflect that it is just one hundred years since Alfred Tennyson was made Poet Laureate.[1] It was the culmination of the most exciting and sensational period in a long and illustrious career. Within a few months, in 1850, Tennyson published "In Memoriam," married the woman for whom he had waited impatiently for 20 years, and received from Queen Victoria the bays that had just fallen from the brows of Wordsworth. To mark the centenary of this extraordinary succession of momentous events, Sir Charles Tennyson, the grandson of the poet, produced a full-length biographical portrait of his illustrious grandsire. It is an intensely human and extremely valuable document. Our libraries are well stocked with lives of Tennyson, it is true; at least a dozen must have been written by skilful and capable hands; but the poet's grandson, free to reveal what his uncle and other writers were under obligation to conceal, has given us an entirely new conception of the poet's personality.

We have always thought of Tennyson as the lordliest of our laureates. There was something princely in his very bearing. On his winning an athletic contest as a student, W. H. Brookfield told him that he had no right to be both a Hercules and an Apollo. Later in life, he was told that, in a braided uniform on the bridge of a battleship, his commanding appearance would ensure the success of any squadron. He compelled a second glance from every man he met. His name still summons to the fancy a figure altogether impressive and magnetic. Yet he has seemed a trifle remote, austere, grandiose, and statuesque.

The Human Aspect Of True Greatness

But his grandson presents for our contemplation quite another Tennyson. On one page we find him setting the rafters ringing with his boisterous laughter. On another, he is weeping beside the white-robed body of his first born, stillborn son—"a grand, massive man-child, noble brow and hands, which he had clenched in his determination to be born." In a later chapter we find him romping on the floor with his children, and anon he is revelling in his favourite game of blind-man's-buff at a young people's party. In his last days, as squire of Farringford in the Isle of Wight, nothing pleased him more than a long chat with the coachman down at the stables, with the ploughboy out in the fields, with the cottagers at their gates in the village, or with an old shepherd for whom he had a special affection. When this aged yokel was told that his familiar companion was the greatest poet living, he threw up his hands in blank amazement. "What a headpiece he must have," the old man cried, "an' 'e doan't look it, do' ee?"

The outstanding vindication of Sir Charles Tennyson's literary venture consists in his ability, denied to his predecessors, to divulge the grim background against which the poet's life must be viewed. The early chapters of the grandson's book furnish a vivid, almost dramatic, revelation of the stark misery of Tennyson's boyhood, a revelation that could not have been made 50 years ago without occasioning serious embarrassment, and perhaps giving mortal offence, to scores then living. It is not a pretty picture. We see the Somersby rectory crowded with a dozen children, of whom Alfred is fourth. The Vicar, who is something of a poet, something of a painter, something of an architect, and something of a musician writhes under a sense of bitter frustration. He is angry with the world for not having made better use of him. He takes to drink; his mind totters; and there are times when, on visiting a parishioner, he is unable to recall his own name.

A Long Lane With a Sudden Turning

Some of the boys, Alfred among them, were sent to the Louth Grammar School. It was a hateful place. Tennyson could never speak of his life there without a shudder. To the end of his days he refused to pass within sight of the buildings. His hand, after a caning, was useless to him for several days. The astounding thing is that, even then, Tennyson was determined to be a poet. If, he said, all the vocations and professions threw open their doors to welcome him, there was only one that he would enter. To be anything but a poet would be an insult to the muse, an outrage on his oracle. It was because of this that the felicities of life came to him so tardily. He was 21 when, in a leafy wood he was introduced to Emily Sellwood by Arthur Hallam, whose memory is embalmed and immortalised in the elegant stanzas of "In Memoriam." He vowed that day that he would marry her; but it was 20 years before the ecstatic dream could be realised.

Once married and crowned, everything went well with him. The Queen and the people took him to their hearts. Tennyson's outstanding distinction lies in the fact that, born in a scientific age, he set to music the new thoughts that were stirring in the minds of men. In him, the aesthetic and the analytic met together; in him, Science and Poesy kissed each other. Yet, side by side with this element of sublimity, Tennyson retained, all through the years, his exquisite simplicity. Neither learning, success, popularity nor wealth spoiled him. As an old man, he one day took his niece, Agnes, for a stroll over the sunlit downs. "You know," he said, taking her arm, "God is walking with us now, on these downs, just as truly as Christ walked with His two disciples on the road to Emmaus. It is the joy of my heart that He is as much by my side at this moment as you are. There is not a flower on the downs that owes as much to the sun as I do to Christ." It was in this spirit that the lordliest and most lovable of our laureates exercised the minstrelsy with which, for more than 60 years, he enriched an attentive and appreciative world.

F W Boreham

[1] This editorial appears in the Hobart Mercury on November 18, 1950.

Image: Alfred Tennyson

Life's Basic Harmonies

Life's Basic Harmonies

Ne'er-Do-Well's Centenary

Ne'er-Do-Well's Centenary Simplicities of Science

Simplicities of Science