7 September: Boreham on Edward Grey

Nostalgia of a Statesman

Nostalgia of a StatesmanWe mark today the anniversary of the death of one of the greatest Foreign Ministers of all time. The dexterity of Lord Grey—better known as Sir Edward Grey—in unravelling the most ominous international complications will never be forgotten. The patience, the tact, the firmness, and the skill that he brought to the momentous negotiations that immediately preceded the outbreak of the First World War have cast a lustre about his name that will never fade. Yet the records that have been published since his death prove that he hated politics and he hated prominence. Publicity stifled him. Mr. Gladstone, with whom Grey was so intimately associated, said that he never met in any man such outstanding aptitude for political life coupled with such pronounced disinclination for it.

Lord Grey's astute and commanding intelligence right be displaying itself amidst the intricacies and perplexities of international diplomacy, but his heart was always out among the green fields, the primrosed woods and the babbling trout streams of the English countryside. Up at Westminster he would give the country of his golden best, but he was secretly longing for his pretty little cottage on the banks of the Itchen in Hampshire. Particularly fond of birds, he knew them both by sight and by sound. Every detail of flight, feather, nest, and egg was familiar to him. He especially loved his wild ducks, and was glad that, when his darkening vision made it impossible for him to watch the smaller birds, his ducks, still flew to him, perched on his arms and shoulders, and remained so still that, even with his blurred sight, he could identify them. Later on, he had to be content with feeling when the ducks took the food from his outstretched hand.

The Refuge Of The Woodland Solitudes

Returning from his parliamentary duties at dead of night, he often left the train at Winchester so that he could enjoy the long country walk, listening to the nightingale calling from the copse, and the sedge-warbler singing beside the river. "I walked," he says, "with my hat off; and once a little soft rain fell among my hair; there was a smell and a spirit everywhere; and it was good to feel the soft country dust beneath my feet." Dr Sclater tells how, beside a beautiful bay in the north country, he once noticed a solitary figure perched on a rock, looking through glasses out to sea. It was Sir Edward Grey, then Foreign Secretary, studying the habits of the gulls. In hours of intense mental stress, when the cruel responsibilities of his exalted office seemed almost to crush him beneath their weight, Lord Grey found the friendship of his furry and feathered companions singularly restful and uplifting.

When, in 1906, his beautiful wife, whom he worshipped, was thrown from her horse and killed, the coffin was laid in the library, and the desolated husband was comforted, as he stood in the doorway, by the sight of the sun streaming in through the open windows and the squirrels coming in as usual for their nuts. His passionate love of wild life was still his solace in those later and still more terrible days when the whole world was convulsed in the throes and agonies of war. He records how, after a worrying week in London, he arrived on Saturday morning at his favourite retreat in the Itchen Valley, with the murmur of the stream distinctly audible. "I am revelling in these delicious hours," he says. "Strolling in the woods just now I passed a poplar tree and from it a wren sprang into the air. Singing in an ecstasy whilst on the wing, he flew straight over me and over the cottage roof to some other place of bliss beyond." It was, he adds, a benediction to him.

The Ministry Of Silent Comforters

In the days in which Lord Grey occupied the limelight with the eyes of all Europe anxiously focused upon: him, and the ears of all the world strained to catch every syllable that fell from his lips, nobody gave much thought to his private emotions and preoccupations. Only his most intimate companions realised that behind the scenes a cruel succession of misfortunes was stripping him of everything that he loved and valued, leaving him at last widowed, desolate, and blind. But those who, through the pages of his biography, find their sympathies awakened by the sheer poignancy of this cataract of sorrows, will rejoice that, to the end of the chapter, the stoats and the squirrels, the wrens and the robins, the seagulls and the wild ducks, solaced his solitude, ministering courage, cheerfulness, and strength. With their aid, he smiled bravely until his last sunset.

Not, by any means, that they were his only comforters. Grey loved books. History, poetry, and romance were very dear to him; but of all the books in which he delighted, one stood out conspicuously from all others. Like Sir Walter Scott, whom he greatly admired, he thought of the Bible as a book apart, majestic, incomparable, sublime. He revelled in its perusal; and, when he quoted it, as he so often did, he quoted it with obvious relish. His face lit up at every such citation. On one of the later days of his life, he went for a long stroll across the moors to Ross Camp, and, after lunching in the open among the heather, stretched himself out at full length, and fell fast asleep. When he awoke, he reflected on the wonderful happiness of his eventful life. "Oh, that men would praise the Lord for His goodness!" he exclaims, in confiding the experience to his journal. 'The beauty of the world is for all who have eyes to see and hearts to feel. I shall die grateful for all the gladness that has been mine!" He did; and, on the anniversary of his death, all who felt the magic of his charming personality share with him that sense of ineffable gratitude.

F W Boreham

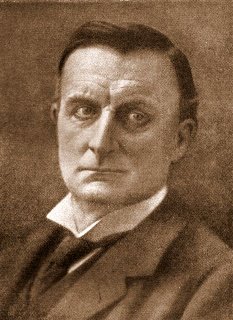

Image: Edward Grey

<< Home