18 September: Boreham on William Hazlitt

Literary Bittersweet

Literary BittersweetWilliam Hazlitt, the anniversary of whose death we mark today, is the most elusive personality in the entire realm of English letters. He spent his whole life in trying to find himself. He searched in many places, and he persisted in the hunt for many years, but he died without having looked himself fairly in the face. As a boy, he thought that he had found himself in the realm of art. Studying under the best masters, he was just beginning to show real promise as a painter when he abruptly changed his mind and tossed his paints and brushes into the fire.

He then attempted to find himself in journalism. With equal vividness and facility he could describe a political sensation, a play, or a prize fight. Following this line of things, he set up in business as a professional critic, and it was here that he first approximated to real greatness. His criticisms were masterly; his contempt was withering; his irony was biting; his invective was terrific. Without qualm or scruple, he tore to tatters some of the finest productions of his time. He bent over his desk and reeled off critiques that made his illustrious victims toss in torture upon their sleepless beds; and then, leaning back in his chair, he wondered why everybody hated him. In utter mystification, he asked Leigh Hunt. Leigh Hunt did not tell him; there was no need; he might easily have made the discovery for himself.

Genius Finds Fame In Sideline

To the extent to which Hazlitt ever really found himself, he found himself in a few essays that he wrote in odd moments, just for fun. They are racy, chatty, fascinating, and free. Although they are the most perfect essays ever penned, each a model of all that a good essay should be, their author never for a moment suspected that they would be cherished by unborn generations long after his piquant and ponderous criticisms had been relegated to limbo and oblivion. The secret of their success lies in the fact that, by means of them, he poured his essential personality on to paper. W. G. Henley and Robert Louis Stevenson were intimate friends; they were born 20 years after the death of Hazlitt; but one of the bonds that united them was their mutual admiration of him. "Hazlitt is ever Hazlitt," exclaimed Henley, "and, at his highest moments, is hard to beat." "We are mighty fine fellows," exclaimed Stevenson, "but we cannot write as Hazlitt wrote," and he more than once confessed that he had sedulously aped the ease, the simplicity, and the charm of Hazlitt's captivating style.

By some strange freak of fate, Hazlitt made it difficult for people to discover the more engaging aspects of his personality. He only appeared amiable to those who treated him with inexhaustible patience and who took infinite pains to find the kindlier side of him. Most people abandoned him as hopeless. Even his wives found him impossible. Women are renowned for their tolerance, but, among all his feminine friends and acquaintances, there were few, if any, who preserved for long any admiration that they formed for Hazlitt.

Prospectors Strike A Rich Vein

Yet, although he repelled almost everybody, there were a few kindly eyes who caught a glimpse of the buttercups among the burrs. John Keats and Charles Lamb were of this select number. They both came under Hazlitt's lash, but they took their castigation gallantly. They recognised that an honest critic, however disturbing and disconcerting, is the friend of literature. "Hazlitt is a good damner," wrote Keats, "and, if ever I am damned, I should like him to damn me!" An even warmer note enters the tributes that Charles Lamb loved to pay him.

Lamb, who demonstrated his devotion to Hazlitt by remaining at his bedside until the last breath had been drawn, assured Southey that Hazlitt was one of the wisest and finest spirits of his time. "I shall go to my grave," he added, "without finding, or expecting to find, such another companion." We may very well leave it at that. There was evidently a genial side to Hazlitt's gnarled individuality. "Well," he exclaimed, in the last sentence that he ever breathed, "I have had a happy life." His happiness has proved contagious, for, whilst his vitriolic criticisms occasioned vexation to a few, his delightful essays have brought unadulterated felicity to tens of thousands.

F W Boreham

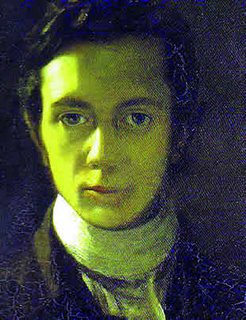

Image: William Hazlitt

<< Home