23 March: Boreham on Thomas Hughes

A Saga of School Life

A Saga of School LifeIt was the proud distinction of Thomas Hughes, the anniversary of whose death was celebrated yesterday, that he enshrined the prosaic annals of a great school in a fragrant atmosphere of classical romance. Close to the railings of the Art Museum at Rugby a fine white marble statue perpetuates his fame. Many boys from Rugby have served the Empire and the world with rare brilliance and effect; but Thomas Hughes, by writing "Tom Brown's Schooldays," has surpassed them all in his glorification of the school and in imparting to its halls a deathless renown. "It is the jolliest tale ever written," Kingsley assured Hughes, many years after its publication; "isn't it a comfort to your old bones to have been the author of such a book?" It certainly was; and to the end of his days, Mr. Justice Hughes was fond of telling of the way in which the inspiration came to him.

He was 33 at the time. His youth and early manhood had been dominated by the spirit of the famous school and of its illustrious headmaster, Dr. Thomas Arnold. It is not too much to say that, just as the history of the world divides itself into two parts—B.C. and A.D.—so the history of the public schools of England divides itself into two sections—before Arnold and after. The distinguished doctor died in 1842, Hughes being then in his teens. Stanley's "Life of Arnold" was published two years later; but although most critics would give it a place among the six finest biographies in the language, Hughes felt, as most of Arnold's old boys felt, that it did not quite convey to the ordinary reader a vivid and realistic impression of the Rugby atmosphere. The thing struck these youthful admirers of Arnold as a trifle stolid and statuesque, if not actually stodgy.

Literary Genius Kindled By Personal Devotion

Hughes said as much one Summer's evening in 1856 in the course of a conversation with John Malcolm Ludlow, the intimate friend of Kingsley. Hughes and Ludlow were both barristers and were sharing a house at Wimbledon. "I have often thought," ejaculated Hughes, "that good might be done by a real novel for boys, not stiff and pedantic like 'Sandford and Merton' but written in a light-hearted and rollicking spirit and aiming only at being interesting." Encouraged by his companion's wholehearted and enthusiastic concurrence, Hughes confessed that he had already set his hand to something of the kind, but, he added with a wry face, he was sure that it was not worth publishing. Brushing aside the young author's modesty, Ludlow insisted on being shown the manuscript, and, a few nights later, Hughes placed it, with many a protest and many an apology, in his friend's hand.

Ludlow was electrified. "I soon found," he says, "that I was reading a literary work of absorbing interest which would place its author in the very front rank of living writers." For a day or two Ludlow could scarcely lay down the engrossing folios. "Tom," he exclaimed, when at length he reached the end, "this must certainly be published! It will be good for you; it will be good for Rugby, it will be good for the whole world." Hughes gradually became infected by his friend's confidence. "I always told you," he wrote to Alexander Macmillan, publisher, "I always told you that I would write a book that would make your fortune, and, surely enough, I have actually done it! I've been and gone and written a one-volume novel for boys. It concerns Rugby in Arnold's time." Hughes meant the note as a frivolous and frothy little joke; but it proved prophetic. Macmillans were then in a very modest way; they had but a small shop at Cambridge; but the popularity of "Tom Brown's Schooldays" set them on their feet and they were soon enjoying an established position among the foremost publishing houses of London. In 20 years the book romped through 65 editions.

To Understand Boys Is To Master & Mould Them

Every boy who has read "Tom Brown's Schooldays"—and what boy has not?—has come more or less directly under the influence of Arnold. With Tom Brown, he has seen the illustrious dominie on the cricket ground, in the lanes round Rugby, in the classroom, and, above all, in the familiar chapel that Arnold has made famous for all time. For the secret of Arnold's amazing success was that he thoroughly understood boys. He knew that a boy has ways of his own, ideas of his own, sensations of his own, and, by the same token, a religion of his own. Arnold never attempted to make religion conventional or stereotyped; but he made it sane, robust and irresistibly attractive. For, as the novelist says, the great event in Tom's life, as in the life of every Rugby boy of that day, was the first sermon from the doctor. We all seem to have seen the oak pulpit standing out by itself above the school seats; the tall, gallant form of its admired and revered occupant; and his kindling eye as he warmed to his congenial and absorbing theme. "And who that had once heard it," asks Hughes, "could ever lose the echoes of the voice, now soft as the low notes of a flute, now clear and stirring as the call of the light infantry bugle, of him who stood there week by week?" Those accents haunted the ears of the boys till their last sun set.

Hughes tellingly describes, too, the long lines of fresh young faces, rising tier above tier down the whole length of the chapel, from that of the little boy who had just left his mother to that of the young man who was about to plunge into the big and busy world. "It was," he says, "a great and solemn sight, and never more so than at that time of year when the only lights were in the pulpit, and the soft twilight stole over the rest of the chapel, deepening into darkness in the high gallery behind the organ." Tom's visit to the doctor's tomb represents one of the most affecting and inspiring scenes in our literature. Indeed, the whole book is quite extraordinary. It is remarkable, not only as a convincing and lively story of school-life that has appealed to every subsequent generation of schoolboys, but as the most eloquent tribute to a noble and knightly personality that has ever been contributed to the stately library of English fiction.

F W Boreham

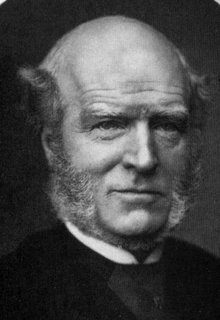

Image: Thomas Hughes

<< Home