17 February: Boreham on Burke and Wills

First Across Australia

It was this week in February, 1861, that Burke and Wills and King and Gray, having pioneered the crossing of the Australian continent, turned their faces southward for the tragic journey home.[1] Beyond the shadow of a doubt the Burke and Wills expedition that, having achieved its end so triumphantly, nevertheless perished so lamentably, was one of the most perfectly-equipped expeditions that ever plunged into the interior of a continent. No expense was spared to ensure its unqualified success. Twenty-six camels were specially imported from India. The men were attended by a long procession of horses and drays and furnished with 21 tons of provisions and paraphernalia. When we remember that Eyre crossed the southern desert and reached West Australia in safety, with all his equipment on his shoulder, it seems an irony of circumstance that these brave men, so liberally furnished, should have died of starvation.

The story of the expedition is one long chapter of blunders. But all those blunders are, in reality, comprehended in one initial blunder—the appointment of a leader. Robert O'Hara Burke was a very brave man, cool, fearless, uncomplaining, and indomitable. As a follower he would have been all that the most exacting commander could desire. But he lacked the first essentials of leadership. He was impatient, impulsive, and unwilling to consider the suggestions of his comrades; he failed most deplorably to win the confidence of those who followed him; he quarrelled with loyal companions on petty issues; he so promoted and so punished his men as to awaken suspicion and distrust; and his vacillating decisions were invariably wrong. It is easy to be wise after the event, but nobody can peruse the records without occasionally speculating on the possibilities of the situation had Burke died at Coopers Creek on the outward journey instead of on the homeward one, and had Wills succeeded to the command.

Expedition Wrecked By Errors Of Judgement

William John Wills was a very gallant gentleman. He was only 26, but he was a student, athlete, competent astronomer, and wise beyond his years. His charming and magnetic personality led the authorities, despite his youth, to appoint him third in command. Landels was second, but Landels and his leader soon quarrelled and Wills was promoted to the vacant place. Over and over again, in the course of that memorable journey, decisions had to be made on which, as it turned out, the fate of the party depended. If on any one of those crucial occasions, Burke had accepted the advice of Wills, the expedition would have returned in safety. But Burke rejected the counsel of his brilliant young colleague, relied —as his duty was—on his own judgment, and the party perished. Perhaps the very modesty of Wills unfitted him for the stern tasks of leadership, and, in any case, there is small profit in dwelling on the might-have-beens of history. The thing has happened and we must take it as it stands.

Yet, for all that, there are few incidents in the world's history that suggest more futile wishes than does that epic story we recall with pride today. If only Burke had waited until he was ready, instead of setting out with one section of his party, leaving the other to follow later! Waiting was inevitable, but waiting in the desert instead of in Melbourne meant devouring during idle days the provisions that were so precious. Again, if only, having made such an arrangement, he had stuck to it and remained at Coopers Creek until his rearguard arrived! Or, since the plan was to be changed, if only Burke and his three companions had set out on their dash to the North a few days earlier! If only, on their return, they had hurried back to Coopers Creek instead of pausing for 24 hours beside the grave of Gray! In either of these events the party that crossed the continent would have reached the stockade before Brahe and his men had evacuated it. As it was, Burke, Wills and King arrived back only seven hours too late.

Toll For The Brave That Are No More

Again, if only, as Wills urged, they had immediately followed Brahe, or waited for a day or two at Coopers Creek, or at the very least, left some clear evidence at Coopers Creek to show they had returned to the depot! For Brahe, a few miles out from Coopers Creek had met the long-delayed rearguard; he then led the entire party back to the familiar camping ground, but failed to notice on his return to it, that the lost explorers had during his short absence, visited the spot. Burke, in the teeth of Wills' entreaties, had decided to strike across country to Adelaide. He argued that, with his exhausted camels, he could not hope to overtake Brahe with his fresh ones. Towards Adelaide they turned their faces and staggered out into the desert to their deaths.

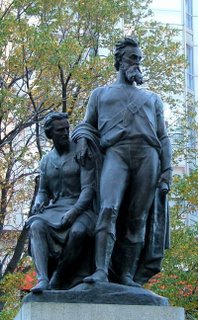

Near Parliament House, Melbourne, there stands a noble monument to the memory of these valiant men. It was the first piece of statuary of which the city could boast, and stood in the centre of Collins St. until the exigencies of traffic drove it farther out. It represents the eager Burke, his hand resting on the shoulder of his young lieutenant, shading his eyes with his hand as he scans the distant skyline, while Wills is making an entry in his journal. The bas-reliefs below depict: (1) The starting of the expedition from Royal Park; (2) the terrible return to the deserted camp; (3) the blacks weeping over the dead body of Burke; (4) the finding of King by the relief expedition. It is a story so full of attractiveness, splendour, and pathos that we in Australia must always regard it as an integral part of our national heritage.

F W Boreham

[1] The actual date was February 21, 1861.

<< Home